iStock

ARGUMENTS ABOUT what to eat and how much to eat, in particular whether to eat more protein or more carbs, will not end any time soon, both because of ongoing research and because, in the end, individuals eventually discover which diet works best for them.

The one constant about protein: Well-run bodies rely on 20 amino acids, 13 of which our bodies produce. The remaining nine “essential amino acids” we get when we digest protein—which involves breaking the protein down into its component amino acids and then reassembling them to create hormones, enzymes, neurotransmitters, etc.

Some experts suggest that adults, especially those over 50, should eat twice the Recommended Dietary Allowance—.36 grams of protein per pound of body weight—which comes to about 45 to 50 grams per day for a 136-pound woman. (You can calculate your own needs here.)

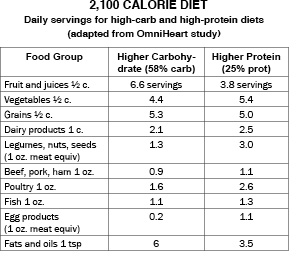

Positive results from the OmniHeart study—with 164 participants, mean age 53.6 years—for the group who ate high-protein diets (25% of calories from protein) include: “Blood pressure, harmful LDL cholesterol and triglycerides all went down when people ate more protein and fewer carbohydrates.” The study concluded: Eat more protein, reduce stroke. These benefits may be gained at least in part because eating more protein means eating less of something else.

Participants ages 52 to 75, in a 2015 University of Arkansas study, who consumed double their protein RDA built more muscle and improved their “net protein balance”—i.e., they were building more muscle than they were losing. Building muscle matters for everyone as they get older because diminishing muscle mass and strength, called sarcopenia, can lead to health problems that include insulin resistance as well as low bone mineral content and density.

“Muscle plays an important role in whole-body metabolism,” Il-Young Kim, the Arkansas study lead researcher, told U.S.News.com. The more protein each participant consumed, the better their bodies were at building muscle.

Kim cites research from Pennington Biomedical Research Center, also in Arkansas, on 25 participants, ages 18 to 35, eating excess-calorie diets. For those who got 15% to 25% of their calories from protein, 45% of the excess calories were stored as muscle—compared with those who got 5% from protein; they stored 95% of the excess as pure fat.

Finally, data from a national health assessment study (NHANESIII) on 6,800 American adults showed an impressive difference in the effects of high-protein diets (20% of calories from protein) for those younger than 65 compared with those older. Participants aged 50 to 64 eating high-protein diets had significantly increased chances of dying from cancer or diabetes—although the effects were reduced, or disappeared, among participants whose high-protein diets were mostly plant-based—while for those 65 and over, the same diet reduced those chances.

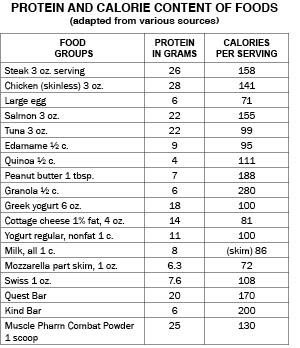

For a 136-pound woman to consume 90 to 100 grams of protein per day—even spread among three meals at about 30 grams per meal—can be challenging. Some opt for the easy addition of protein powder, such as Muscle Pharm “Combat,” which packs 28 grams of protein into 130 calories, consumed with water or milk as a protein shake. Others prefer the taste of Quest bars, with 20 grams of protein for about 170 calories, but not nearly as scrumptious as Kind bars, though these come in at 6 grams of protein and about 200 calories. Enthusiasts say both the high-protein powders and bars make them feel more energetic.

Protein comparisons of different foods can be surprising (see chart right below): Three ounces of chicken have more protein and fewer calories than the same amount of meat, meaning beef, lamb and pork; six ounces of Greek yogurt have more protein than one cup (eight ounces) of plain yogurt, with both choices worth about 100 calories; and all grades of milk, from skim to whole, have the same amount of protein, 8 grams per cup, with total calories increasing from skim to whole. (In questions about high- versus low-fat dairy, one Australian study of short-term diets found that eating low-fat cheese and yogurt did not improve the inflammation associated with cardiovascular disease when compared with the full-fat products.)

Also surprising is the comparison of foods in the OmniHeart study included in the high-carb diet (58% of food consumed as carbs)—fruit and juices, fats and oils (see chart); versus those in the high-protein (25% protein) diet—legumes, nuts, seeds and other vegetable proteins, and poultry (see chart below).

When making choices among different kinds of protein, the Harvard Health Blog is equivocal, stating first that “mounting evidence shows that reducing animal-based proteins is a healthier way to go,” and then proceeding to suggest “switching just one serving of red meat per day for poultry, fish or plant-based protein.” (Who eats more than one serving of red meat per day, and why isn’t poultry considered animal-based protein?)

Diet recommendations that are confusing or conflicting give way to personal needs and preferences. On one hand, for example, granola is an inefficient means of getting sufficient protein, if eating a reasonably sized portion: Half a cup of granola (6 grams equaling 280 calories) with one cup of 2% milk (8 grams or 122 calories) equals about 14 grams of protein at about 400 calories, while ½ cup of Greek yogurt provides 18 grams at only 100 calories. For those eager to start their day with granola, however, there’s the MIND diet for brain health, which recommends three or more servings of whole grains per day.

For true protein efficiency, powdered protein has no equal—and maybe none in the terrible-taste department either, although many people come to enjoy it. There’s the rub: how far to move your diet away from personal preferences based on studies with small numbers of participants or recommendations that change more often than the seasons.

The main motivator for making diet changes is ill health. But when that’s not an issue, if caring for your mind is of greater concern than working your muscles, dig into that granola.

Just don’t forget the powdered stuff is there when you need it.

—Mary Carpenter

Mary Carpenter is the Well-Being editor of MyLittleBird. Look for her story on sunscreens coming later this fall.

Excellent overview. Greek yogurt was the big Takeaway for me.