The wheel of emotions.

By Mary Carpenter

WRITING DOWN answers to Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) questions— in a small CBT workbook handmade by a friend—led me to a startling revelation: Self-directed CBT that requires written responses works better for me than previous efforts employing “self-talk,” which ranged from how-great-I-am mantras to reframing negative thoughts, a la Brené Brown.

(What my friend said inspired her gift was that she herself had found the exercises helpful. But I suspect that a bigger reason may have been that listening to me get upset about the same family issues over and over made her think I might benefit—and even not need to talk about them so much … .)

As surprisingly impressed as I once had been after watching therapists’ video recordings of CBT sessions—at how these sessions provided dramatic help to patients—I have been more so by the power of my friend’s gift. One advantage for me may be the book’s unintimidating 7-inch-by-5-inch size; full-size, commercially published CBT workbooks, notably Retrain Your Brain: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in 7 Weeks by University of Pennsylvania psychologist Seth Gillihan, abound.

“One of the goals of CBT is to become your own therapist by learning skills you can use on your own,” writes Gillihan in a National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) blog, adding: “What drew me to CBT was how straightforward and intuitive it was, which also makes it well-suited for self-directed therapy.” In addition, Gillihan describes two reviews, each including more than 30 studies, that found “self-help treatment significantly reduced both anxiety and depression, especially when the treatments used CBT techniques.” “The central idea behind CBT is extremely simple: If you change the way you think, you can change the way you feel,” writes nurse and blogger Risa Kerslake. “But if feeling better…were that easy…” Kerslake describes her “anxiety hangovers,” waking up on the day after an event feeling horrible about everything.

Using the “triple column technique” for written, self-directed CBT, Kerslake explains that “negative self-talk, that crappy mean little voice inside your head,” goes in the first column. In the second, she records cognitive distortions—described by Cleveland Clinic as “unhelpful patterns of thinking…based on problematic core beliefs, including central ideas about yourself and the world.”

Distortions, such as “‘should’ statements,” “personalization (self-blaming), “overgeneralization” and “jumping to conclusions,” arise in statements “the little voice makes about who I am and what’s going on in my life,” writes Kerslake. By writing down these little-voice statements, she notes, “it always looks kind of shocking to see [them] in print.” Writing down upsetting thoughts can make it easier to view them with distance and more logical thinking, to see the “cognitive distortions,” and then to respond to the subsequent questions and ultimately come around to a less fraught way of thinking about the experience. (The little book from my friend includes “20 Cognitive Distortions,” along with short descriptions for each.)

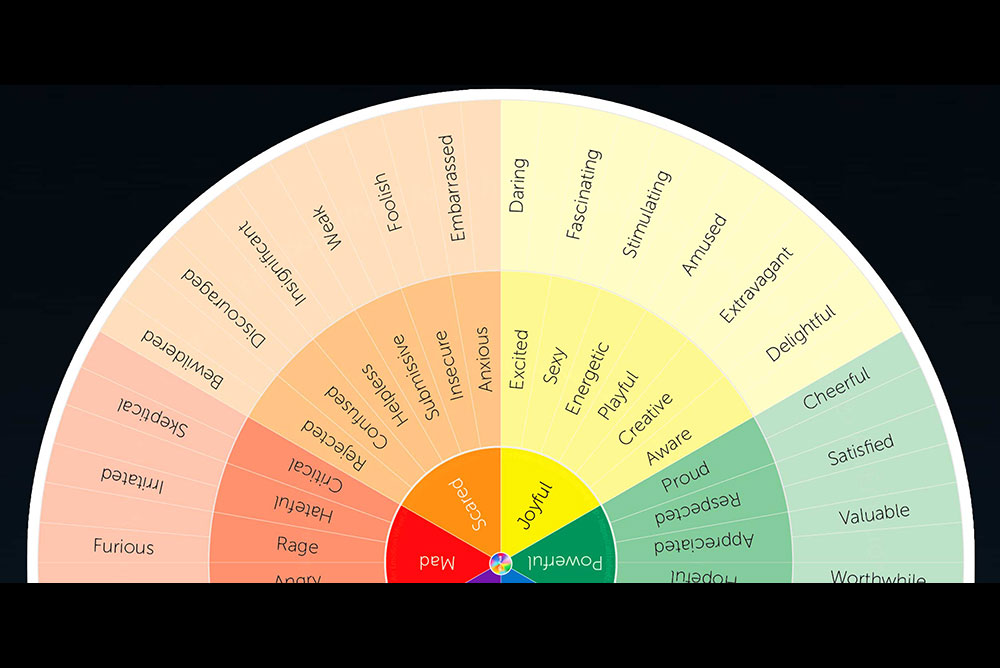

The “Wheel of Emotions” on another page of my book depicts colorful rings that expand outwards and contain words describing feelings. The wheel is “especially useful for moments of intense feeling and when the mind cannot remain objective as it operates from an impulsive ‘fight or flight’ response,” writes Hokuma Karimova on Positive Psychology. The goal is not to replace negative motions with positive ones but to identify and accept an emotional experience.

The wheel’s central circle lists primary or basic emotions—such as scared, sad, mad and glad—with different iterations of the wheel employing variations in the number of emotions and their labels. Moving outwards, subsequent rings include different combinations and intensities of emotions so that anger can mean anything from annoyance to fury while fear ranges from timidity to terror.

“This Wheel of Emotions diagram beautifully depicts the relationships between each emotion in the form of a spectrum,” according to Therapist Aid. “We like to use this worksheet with clients who have a hard time picking out the right word to describe how they feel. Even if the word they want isn’t on the spectrum, they might be able to point out what it’s near.”

My book’s final section encourages writing with tear-off workbook pages that pose five questions and leave blank spaces for recording answers. The first three questions ask for descriptions of “What happened?” “What is going through your mind?” and “What emotions are you feeling?” The final two encourage reflection: “What thought patterns do you recognize?” and “How can you think about the situation differently?”

For me, the main reason I actually performed self-directed CBT may be the kindness of my friend who put together my little book with paper, glue, cardboard, ribbon and a cover of decorative paper. Also the small size of the book and the spaces for writing made the work appear relatively undaunting. While I tried the three-column method only once, I have continued to use the little book.

“What happened” to me recently, for example, was running into R.L., a long-time friend who greeted me with a smile and cheery “hello,” despite having dropped me about five years ago with no explanation. “What was going through my mind”: I must be deeply flawed or have done something unforgivable to cause her to drop me. For “emotions,” I wrote: victimized, powerless, vulnerable, abandoned, which fall into the wheel’s “Sad” section; along with some from the “Anger” section, including irritated and embarrassed.

The first cognitive distortion I listed was “self-blaming, which led me to emotions such as inadequate, worthless, insecure–listed in the “Fear” section of the wheel. For “Challenge Your Thoughts,” I remembered that R.L. had dropped at least one very old friend during the period of my friendship with her. Also, I noted that I had made wonderful, loyal friends over many decades. After writing, I breathed a little more easily; also I hoped never to give R.L. another thought.

—Mary Carpenter regularly reports on topical subjects in health and medicine.