‘TIS A disease which attacks not only the Breast…It sometimes assumes different names; when it comes on the Legs, ‘tis called the Wolf, because if left to itself, ‘twill not quite them ‘till it has devoured them —1707 description of cancer by French surgeon Pierre Dionis.

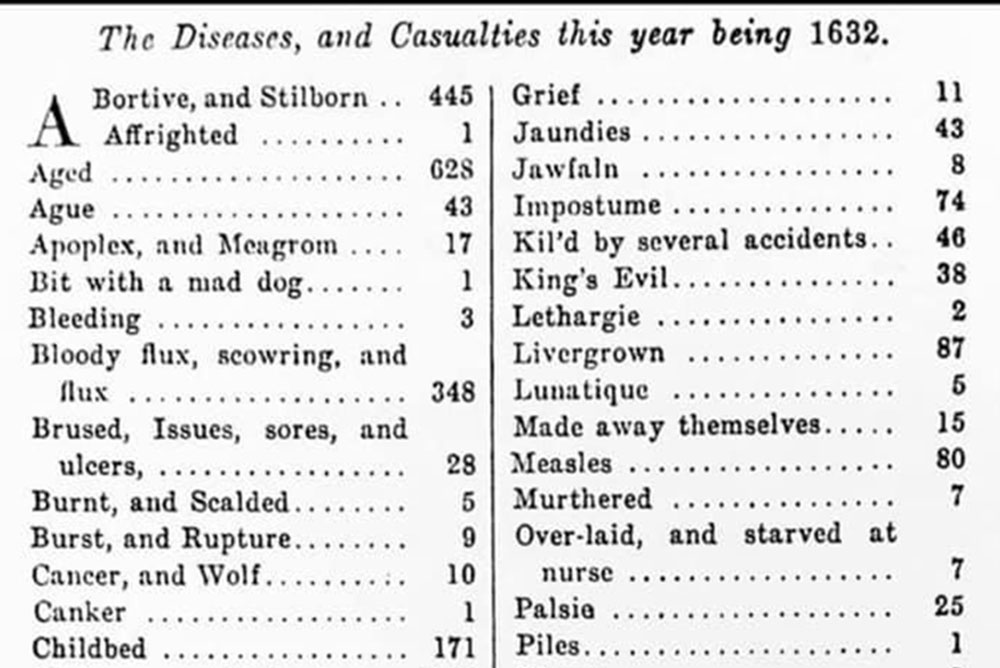

The Wolf in Cancer, and Wolf is one of many entirely unfamiliar terms on a 1632 “Diseases and Casualties” list—sometimes printed on the backside of “Bills of Mortality.” Other names are familiar but surprising causes of death, like piles; familiar but with generally unknown definitions, like dropsie; and familiar with definitions that are surmisable, like flux.

Some terms are still in use but with different definitions or grouped differently, such as meagrom with apoplex; and some are still used but as euphemisms, like French Pox. By 1665, the most common cause of death in London was bubonic plague—killing about one-fourth of the city’s population.

“Nasty, poor, brutish and short” was how Thomas Hobbes described life in 17th-century England. But in the American colonies, even more “horrifying mortality rates” led England to send shiploads—in one, of approximately 1,500 kidnapped children to the Virginia colony; and in others, of “unemployed, vagrants, and other undesirable multitudes.”

Among unfathomable “Diseases and Casualties,” Planet (or plannet) was “likely a shorthand for “planet-struck [because] Many medical practitioners believed the planets influenced health and sanity.” The label applied to any sudden illness or death, such as a heart attack or aneurysm, according to “15 Historic Diseases that Competed with Bubonic Plague.”

Likewise, King’s Evil came from a belief, in this case that the touch of a king would bring a cure—for scrofula, a tuberculosis infection of the neck glands. Another label that embodied more than medicine was Impostume—a swelling, cyst or abscess, usually filled with pus, but with the “metaphorical meaning of an egotistical or corrupt person ‘swollen’ with pride.”

A popular listing, Rising of the Lights referred to “literally coughing your lungs up,” because lights was a familiar name for lungs, considered lightweight organs when referring to edible organ meats, in this case haggis. The diagnosis covered croup, pneumonia and any illness characterized by a hoarse cough or choking sensation.

Livergrown indicated an enlarged (failing) liver, diagnosed by symptoms such as jaundice and abdominal pain. And Cut of the Stone described death during surgery for bladder or kidney stones. Tissick came from the now-obsolete phthisis, wheezing and coughing associated with asthma or possibly tuberculosis.

Besides Piles (hemorrhoids), terms that are still familiar but surprising as causes of death include Winde, Sciatica and Falling sickness. Also, Surfet, or overeating—which may have referred to death from eating too much of a food that becomes poisonous in large quantities, as with King Henry I and lampreys; but may also have included death due to untreated diabetes and other causes of overweight, or to excessive drinking.

Among terms that remain familiar, Dropsie (dropsy) refers to swelling of soft tissues—though today’s diagnosis would specify cause, as in edema due to congestive heart failure. And flux, appeared on the list as Bloody flux, scowring, and flux, with each term referring to dysentery.

Quinsie, from the Latin word meaning choke, described an abscess that can arise behind the throat as a complication of tonsilitis. Tympany referred to swelling or bloating in the digestive tract that produced a hollow sound when tapped and could be fatal if caused by kidney disease.

Pox, still used as a generic description, appeared on the list as Flocks, and small pox, Swine Pox and French Pox—all originally diagnoses of venereal disease, usually advanced syphilis, but the latter term endures as a British euphemistic slur for French licentiousness.

Among antiquated groupings, Apoplex, and Meagrom combined various kinds of severe head pain that resulted in death—with apoplex signaling stroke and paralysis resulting from stroke; and meagrom, all other head injury and pain. In the modern version, apoplexy refers to unconsciousness or incapacity from the same original causes but can also refer to speechlessness due to extreme anger; and migraine indicates specific kinds of headaches.

Another grouping, Colick, Stone, and Strangury, refers to severe abdominal pain, usually causing death without a more specific diagnosis—but which could also indicate bladder/kidney stones or ruptured appendix. Strangury alone meant—and continues in Chinese medicine to mean—painful, frequent urination, in which “drops’ of urine are ‘squeezed out.’”

For Purples, and spotted Feaver, in the combination spotted fever referred loosely to any typhus or fever accompanied by reddish skin eruptions. Purples alone indicated bruising, especially when widespread; or to broken blood vessels caused by underlying illness, including scurvy or a circulation disorder.

Viewed from today, some old names seem more direct than current labels, such as Made away themselves — now, committed suicide, or the increasingly used suicided. And Suddenly suggests the jolting emotional effect on others of sudden unexplained death—compared to today’s term, cause of death unknown.

While Consumption was the most frequent reason for adult death (1797) on this list, almost 2,500 deaths to infants occurred from the combined causes of Childbed; Over-laid, and starved at nurse; and Chrisomes, and Infants—the latter referring to deaths that occurred in the first month of life, around the time of baptism using white cloths called chrisomes.

“The infant mortality rate would fluctuate sharply, according to the weather, the harvest…severe times, a majority of infants would die within one year,” according to “The First Measured Century” on PBS. While life expectancy by the mid-Victorian era barely exceeded age 40, “dramatic declines” in infant mortality in the 20th century led to “equally stunning” increases in life expectancy.

—Mary Carpenter

Mary Carpenter usually reports on current medical and health issues.

Great idea for a post! The history of disease and medicine is fascinating, and this piece introduced me to several terms I wasn’t familiar with. But I’ve done a fair amount of research in primary sources from the late 18th century, and it’s clear some things hadn’t changed much since the previous century. I’ve seen obituaries in 18th century newspapers that said vague things like “carried off by a severe chill.” Pneumonia? Who knows?

And if you feel like you’re glad to be living in this century after reading this, just wait until you hear about some of the TREATMENTS for these diseases, many of which required bleeding and/or purging. (Maybe the author can tackle that next!) Still, some of the old herbal remedies have come back into favor — e.g., in herbal teas.

Thanks for doing this!

Pretty grim – but so interesting to read! Thanks! I love learning new things through My Little Bird.

Fascinating. I’m glad to be living in this century…

Brilliant historical perspective on plagues of old….thank goodness for modern vaccines.

Thank you!