iStock

By Mary Carpenter

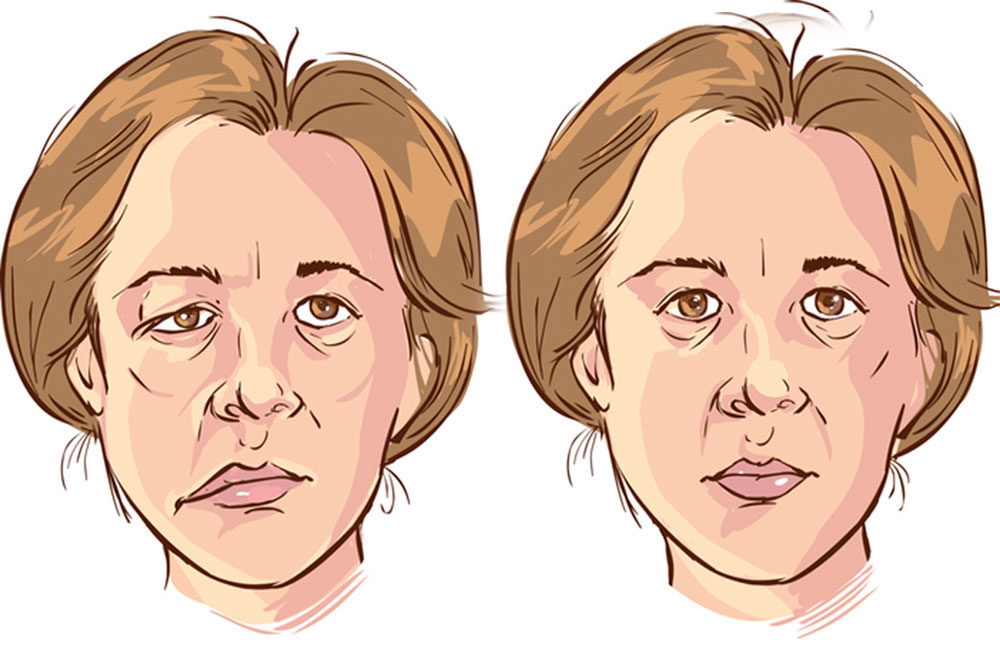

IMAGINE FEELING well enough for daily activities—except that one side of your face droops, involuntarily produces smiles or squints, contracts, or stiffens to the point of becoming immobile and expressionless. You may also experience intense pain, and drool or shed crocodile tears (tears with no emotional cause).

Paralysis that arises suddenly, affects only one side of the face and worsens over 48 hours often signals Bell’s Palsy—in the news lately as a possible if disputed side effect of Covid vaccination, writes Apoorva Mandavilli in the New York Times. Known to occur following other vaccines, Bell’s Palsy affects about one in 60 people during their lifetime, and is becoming more prevalent.

Sudden drooping or stiffening of one side of the face could also be a worrisome early sign of stroke— though these rarely affect the forehead or eyes. Also, a stroke causes muscle weakness in other parts of the body as well, hence the early stroke-detection method FAST that includes raising both arms.

Swelling in the facial nerve leads to ischemia, a restriction of blood and oxygen to the nerve cells: the seventh cranial nerve has so many functions that any disruption can lead to symptoms that vary from person to person. One explanation for the rising incidence of Bell’s Palsy is increasing numbers of herpes zoster infections—which are present in most cases of Bell’s Palsy, although the condition is considered idiopathic (no known cause). In addition, Bell’s Palsy recurs in eight percent of sufferers.

Facial-nerve paralysis dates back at least 4,000 years, based on representations in Egyptian sculptures, and asymmetrical and distorted faces appear in paintings from the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The uneven smile of Mona Lisa’s portrait has been the subject of facial-nerve symposium presentations.

Bell’s Palsy also arises after infection with the flu or Lyme disease, in pregnant women, and in those with type 2 diabetes; and is more common between the ages of 15 and 60, with peak incidence around age 40. Stress and high blood pressure may play a role in setting off symptoms—and may themselves be exacerbated for sufferers when symptoms arise with no clear end point. Some cases take several months to resolve, although most symptoms disappear within two weeks, and 90% of sufferers recover completely.

The pain of Bell’s Palsy often occurs behind one ear or as headache, and other symptoms involve loss of taste and hypersensitivity to sound (hyperacusis). Some sufferers cannot close the eye on the affected side, even during sleep. A rare symptom, synkinesis—when facial muscles move in tandem—can cause simultaneous smiling and blinking. The label “refrigeration palsy” comes from the common memory among sufferers, soon before symptoms begin, of “cooling of the face or a cold draught,” or exposure to cold, such as driving or sleeping with a window open in cold weather.

Bell’s Palsy rates were higher during the cold seasons in a two-year study of active-duty military service members, who have a higher incidence of the condition. In this group, climate that was both cold and arid appeared to increase risk, although incidence was higher in the southern region of the United States than elsewhere. Also, sufferers spent more time indoors than the “lower-injury group,” leading to the hypothesis that dry indoor air—heated but not humidified—could “traumatize mucus membranes… in turn, induce reactivation of the herpes virus.”

Treatment for more serious Bell’s Palsy can include oral acyclovir starting within three days of the first symptoms, along with steroids to reduce inflammation. Botox has also helped speed recovery from the drooping. Famous sufferers of Bell’s Palsy include George Clooney, Roseanne Barr, Sylvester Stallone and Angelina Jolie, who believed sessions of acupuncture helped her recover.

Incidence of Bell’s Palsy rose early in the pandemic—with a 6.85 increased risk in those who had Covid, according to the Jama study. But connections to the vaccine are less clear. As of April, 2024, Americans have received nearly 677 million doses of Covid vaccine. Among these, “just over 13,000 vaccine-injury compensation claims have been filed with the federal government,” with sufferers complaining about lack of follow-up.

The CDC has documented only four serious but rare side effects of the vaccines—all of which occur after many other vaccines—with two linked to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine no longer available in the US.: Guillain-Barre syndrome and a blood-clotting disorder. Another, seen mostly in boys and young men following the mRNA vaccines, is heart inflammation or myocarditis; and the final is anaphylaxis, an allergic reaction.

Not enough evidence for the “vast majority of side effects” was the conclusion in April from a panel of experts convened by the National Academies. But FDA’s director of Evaluation and Research Peter Marks told the New York Times: “I do believe we could do better.” While any report on worrisome side effects of the Covid vaccine risks fueling the politics of anti-vaxxers, I suspect better attention could be paid to these sufferers, whose complaints are regularly dismissed by the medical profession.

—Mary Carpenter regularly reports on topical subjects in health and medicine.