iStock

By Mary Carpenter

LOCAL nonprofit founder L.D., who swims and walks regularly, spent a morning shivering on the couch. Trying to take a shower, she became so dizzy she crawled out on her hands and knees. As the day progressed, she began shaking uncontrollably and felt cold under heavy blankets as her fever rose to 102. At the hospital on her doctor’s advice, ER physicians diagnosed sepsis, transferred her to an in-patient bed and started IV antibiotic treatment.

The Covid pandemic has shined new light on sepsis because of overlapping symptoms, including those experienced by L.D. Also, the two conditions operate via common mechanisms: overreaction of the immune system to infection leading to system-wide inflammation, called a “cytokine storm.” In addition, Covid infection can make sufferers more susceptible to other infections, making diagnosis and treatment more complicated.

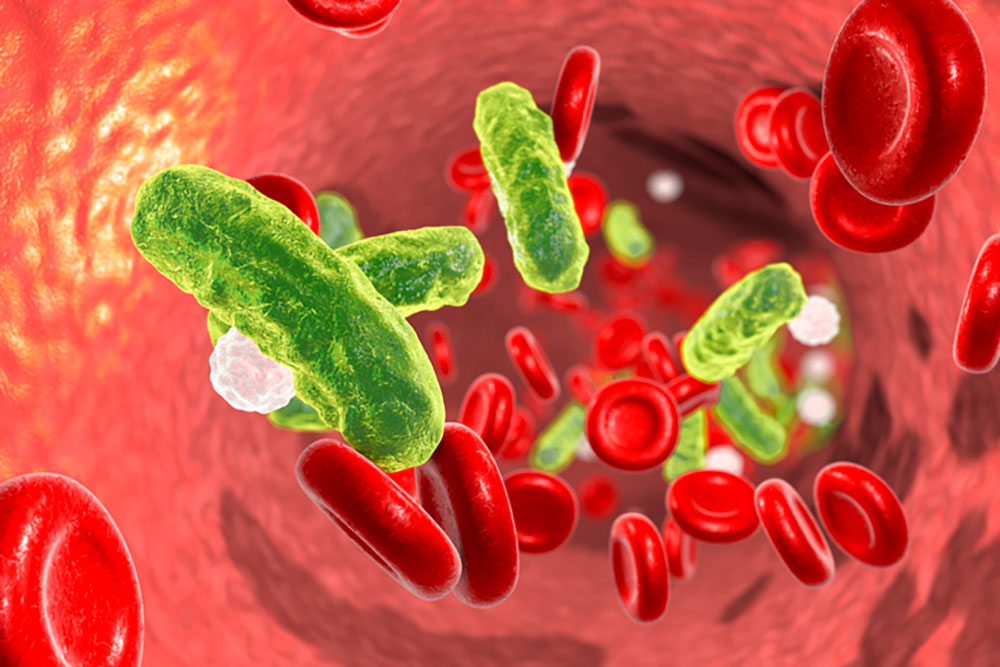

“Whenever the immune system is highjacked by a microbe, the body’s defenses can become self-destructive,” explains New Jersey surgeon Richard Marfuggi and colleagues on STAT. “The pathogens shut down one part of the immune cascade while shifting another part into a hyperactive state.” The result is the creation of micro-clots capable of cutting off blood supply to the organs and causing them to fail.

Rapid treatment of sepsis is important: Every hour delay increases the “odds of a poor outcome by 3 to 7%,” according to STAT. But difficulty pinning down the cause and location of the infection can make sepsis tricky to treat. In most cases, the villains are bacteria—in the lungs (pneumonia), the urinary tract (UTIs) and abdomen (appendicitis)—and will respond to antibiotics. But other infectious agents, such as the virus causing Covid, require different kinds of drugs.

Sepsis kills about 350,000 Americans each year, including up to 40% of those who develop severe sepsis and septic shock, making it the most expensive in-patient therapeutic cost and the most costly in-patient condition covered by Medicare. More than 80% of people in one survey were unfamiliar with its symptoms—compared to recognizing signs of stroke (facial droop and slurred speech) and heart attack (chest and left arm pain)—as well as with the acronyms designed to help recognize sepsis.

The acronym TIME refers to “temperature, infection, mental decline and extremely ill,” according to PennMedicine. And “SEPSIS denotes shivering, extreme pain, pale skin, sleepiness, I feel like I might die, and shortness of breath.”

“Apart from a few major academic medical centers, most patients and clinicians lack access to the latest diagnostic technologies,” according to the STAT editorial. The result can be “disease progression that makes patients sicker, more likely to need hospitalization and more difficult to cure.”

In L.D.’s case, her original infection was a UTI, and her ER diagnosis was pyelonephritis—inflammation of the kidney due to bacterial infection. According to UrologyHealth, E.coli and other bacteria that live in the intestines can travel upwards into the urinary tract via the urethra and on up into the bladder, causing either cystitis (inflammation of the bladder) or a UTI. From there, bacteria can proceed up the ureter into the kidneys.

“The body often can fight off simple UTIs on its own,” according to Medstar Health. AZO, the OTC pain reliever phenazopyridine, deals with symptoms of pain, burning, increased urination and the increased urge to urinate, but doesn’t treat the infection. Prescribing antibiotics for a potential UTI usually depends on the presence of multiple symptoms, such as fever or burning sensation while urinating.

About 1 in every 30 cases of UTI leads to a potentially dangerous kidney infection, more commonly in women who have frequent bladder infections or anything that blocks urine flow, such as kidney stones and structural problem in the urinary tract. Also, UTIs occur more often in postmenopausal women, whose bodies produce less estrogen, making the urinary tract more susceptible to bacterial growth. “Treatment bundles” for sepsis include medication to treat the infection and infused fluids to encourage blood circulation and recovery.

As sepsis continues to deserve better attention, the Covid pandemic may be waning. In last week’s New York Times final “Virus Briefing” email, which began March 2, 2020, science reporter Carl Zimmer wrote: “Nearly 4,000 Americans died just last week of Covid-19—from a disease that did not exist four years ago. Sixty-five million people are estimated to have long Covid…SARS-CoV-2 is continuing to evolve in surprising ways. This story is not over.” National reporter Mitch Smith writes, “I’m struck by how far we have come and how far we have not. Covid, rather than becoming a past-tense plague, has remained a present-tense threat, even if it’s less of one before…”

Deaths from Covid now amount to around 180,000 a year, still a much higher number than the 12,000 to 52,000 annual deaths associated with flu. These totals, however, remain much lower than than the 350,000 each year linked to sepsis.

And even when sepsis is not the diagnosis, symptoms such as shivering and feeling clammy can signal serious infection: a friend with these symptoms recently needed immediate treatment for pneumonia. But for the only other person I know who developed sepsis, early 50s DC-based filmmaker L.K., the original infection came from a cut on her toe. Because I have peripheral neuropathy that causes diminished feeling in my feet, I watch out, take care and see a doctor when I’m worried.

—Mary Carpenter regularly reports on need-to-know topics in health and medicine.

Thank you for an incredibly important column.

This is the kind of information we can all use. Much appreciated.