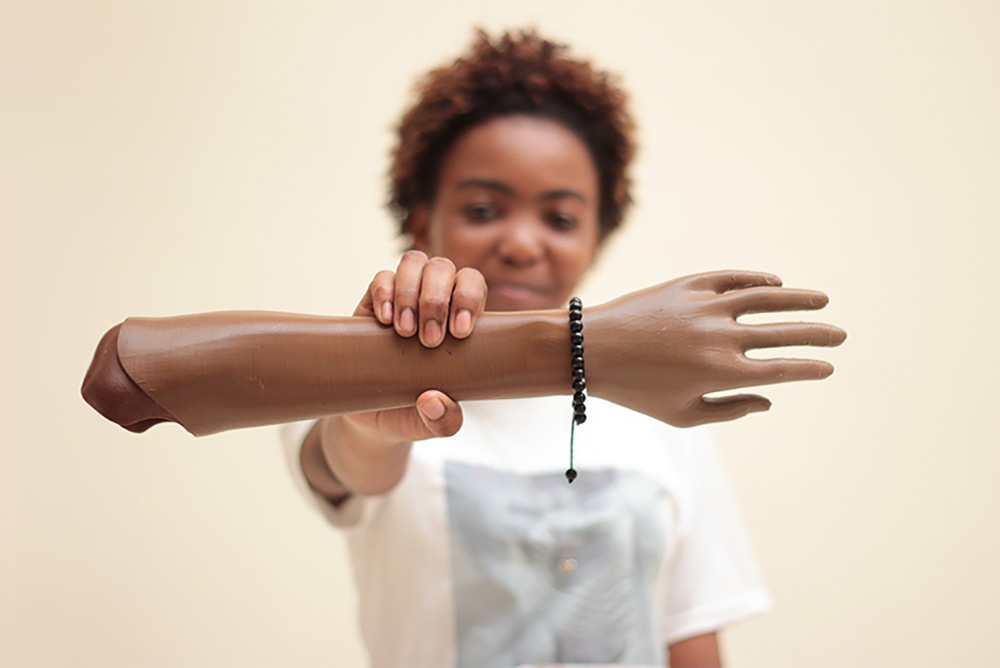

Ebe, a LimbForge patient in Haiti, with her 3D-printed prosthetic arm, an evolved version originally crafted by Arthur Hobson and Jeff Erenstone. LimbForge is an organization dedicated to aiding the shortage of prosthetic rehabilitation in the developing world. / Photo courtesy of LimbForge.

By Mary Carpenter

THAT TREATING infection has garnered the greatest medical advances in wartime is one highlight of the recent exhibit, “Bespoke Bodies,” at Kansas City’s World War I museum. In addition to covering infection-related amputation, the display cases feature revolutionary developments in prosthetics–and portray women dressed in short skirts and short sleeves that proudly reveal prosthetics decorated in gold leaf, lace and fine-art drawings.

“Most people with limb loss…today are not veterans or survivors of war,” writes Lindsey Roy in a Teen Vogue article. In photos from her KC visit, Roy shows off her below-the knee prosthesis, acquired after the 36-year-old mother and Hallmark Cards executive lost her leg in a boating accident. Roy chose an undecorated but Bluetooth-enabled model for better movement control but describes innovations that give high-fashion models “access to customized, alternative limbs.”

Amputations soared in World War I with the advent of machine guns and tanks, resulting in amputations for about 100,000 Britons and Germans “when the procedure was often the only one available to prevent death,” Roy reports, quoting the Wall Street Journal. But in every war since then, more soldiers continue to die of infection—whether coming from outside the body to cause wound infections, or from viral and bacterial infections that attack from within.

“It takes a thief to catch a thief” is the mantra that came from antibiotic research that surged during World War II —referring to new drugs created by modifying viruses and bacteria. Before that, isolation was the only weapon for fighting these dangerous beneath-the-skin infections, according to The Life Savers of World War II, by Wendy Schoenbach Reasenberg and Anna Kade Schoenbach. In 1941, during the months after Halifax, Nova Scotia, became a major port through which thousands of soldiers moved, the only response U.S. medical teams could mount against three simultaneous epidemics—diphtheria, scarlet fever and meningitis—was mass quarantine and testing.

The next challenge for U.S. medical teams during that period was to develop antibiotics—which even today involves modifying infectious agents sufficiently to kill the virus or bacteria without creating side effects in patients. Life Savers describes an early candidate, streptomycin, which rather than treating, acted as a growth factor for infectious meningitis. And the greater problem that has emerged since then is antibiotic resistance developing in the most dangerous bugs—notably Clostridium difficile (C.diff) “associated with severe infections, high rates of recurrences and mortality.”

“That resistance out there is actually now one of the leading causes of death in the world,” Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Director Chris Murray told NPR. According to the report, “bacteria are mutating to evade antibiotics at a pace far faster than many researchers had previously forecast.”

The failure of antibiotics—always thought to be a so-called first world problem—is now “happening all over the world [with] deadly new strains of bacteria…causing untreatable blood infections, fatal pneumonia, relentless urinary tract infections, gangrenous wounds and terminal cases of sepsis, among other conditions,” according to the article. “Minor wounds that in the past may have needed only a bandage are now developing multidrug-resistant infections.”

Limb amputations in the U.S. today number almost 500,000 per year, mostly in patients with diabetes and vascular diseases, according to the Amputee Coalition. While lower smoking rates have brought down the numbers of lower-limb amputations, increased rates of diabetes, peripheral artery disease and chronic kidney disease have kept the total numbers high. And for veterans, wound infections still rank as a major cause.

Meanwhile, decorative innovations have begun appearing on medical devices—from ostomy bags to hearing aids—that address a range of medical issues. Diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, British designer Destiny Pinto used weightlifting gloves to support her wrists and compress aching joints and found that both discomfort and the embarrassment related to her condition decreased with the addition of fashionable accessories—adorning “red hot compression gloves … with silver buckles or [wore] lacy white gloves decorated with roses.”

OTC braces, often bulky and beige, have been my only experiences with medically assistive devices—for issues with ankles, knees, hands and wrists. But when the white wrist brace became slightly soiled from use, I dyed it bright blue: then, instead of questions related to disease and injury, people asked me about dyeing. And I had a much better time—telling dyeing tales from long-ago days in my hippie commune.

—Mary Carpenter regularly reports on topical subjects in health and medicine.

Love being educated