iStock

The incidence of Lyme disease is increasing, so we thought it timely to rerun—with a few updates—Mary Carpenter’s post from last July about how to protect yourself.

IN THE LAST year, Lyme disease has moved into all 50 states, and reported incidence of all tickborne diseases has increased to around 40,000 cases, although, based on estimates of 10 undiagnosed cases for every one reported, the nationwide total for 2017 came closer to 400,000, almost 20% more than that reported in 2016.

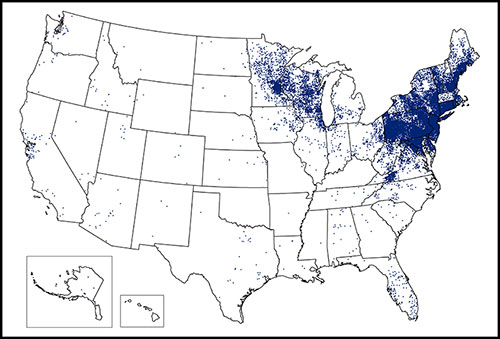

2017 Reported cases of Lyme disease in the United States. One dot placed randomly within county of residence for each confirmed case. / CDC

Data from New Jersey-based Quest Dynamics show “positive results for Lyme are both increasing in number and occurring in geographic areas not historically associated with the disease,” according to CBS news. Quest researchers wrote: “We hypothesize that these significant rates of increase may reinforce other research suggesting changing climate conditions that allow ticks to live longer and in more regions may factor into disease risk.”

To reiterate our advice, it’s time to ratchet up anti-tick measures. Wear light-colored clothing to make ticks easier to spot—and long pants tucked into socks.

Spray the insecticide (as opposed to insect repellent) permethrin on clothing and repeat after every one or two washes. A local tree expert gives Repel to his crew but warns that “a little does not go a long way”—so spray heavily. What might be easier over time is purchasing pants pre-treated with permethrin, on which effects last through dozens of washings.

In conjunction with insecticides, apply insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin and lemon eucalyptus oil directly on the body. After walking in grass or any vegetation not closely trimmed, take a hot shower within two hours of being outdoors. Check your clothes and body—ticks love warm, moist areas like armpits, hair and especially groin areas—although the nymph or juvenile tick that most often transmits Lyme disease can be hard to spot, “with bodies as small as a freckle or the tip of a pencil.” Wash clothes in hot water; before or instead of washing, dry for 10 minutes in a hot dryer.

And protect predators of the white-footed mice, crucial to the larval stage of the life cycle of Lyme-carrying ticks and considered primary vectors of Lyme disease. As many as 90% of white-footed mice carry the Lyme bacterium, and an individual mouse can carry up to 100 ticks at a time. If you see a mouse or signs of mice indoors, take immediate action. At the next stage, the nymphs are most dangerous to humans, and adult ticks live and mate on deer, which are responsible for spreading the larvae.

Be especially kind to neighborhood foxes. When predatory animals such as red foxes proliferate, prey animals like mice show decreased movement and increased hiding behavior: “The mice are too busy hiding from foxes to end up as tick food,” according to Arlington Patch.

If you find a tick attached to your skin, remove it as soon as possible—within 24 to 36 hours, before the tick has the time to inject the Lyme bacteria—and save the tick. If you experience Lyme symptoms, such as fever and muscles aches, without the characteristic bull’s-eye shaped rash—which occurs in only around half of Lyme cases—showing the tick to medical professionals can help persuade them to begin antibiotic treatment.

Because blood tests to detect Lyme disease rely on the development of a measurable immune response, it can take 10 to 30 days before tests show a positive response. But sometimes symptoms alone are clear—and often severe—enough that doctors will begin treating right away.

Because some doctors underestimate Lyme risks and dismiss reports of symptoms, a physician familiar with tick-borne diseases may provide the best treatment, advises Kris Newby, producer of the Lyme disease documentary Under Our Skin. “Don’t waste valuable treatment time trying to convince an inexperienced physician that you’re really sick.”

Newby advises contacting the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society for a list of local practitioners. Locally, the Johns Hopkins Lyme Disease Research Center is a resource for treatment of Lyme, in particular “Post Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome” – persistent symptoms that affect a subset of patients with Lyme disease, especially those who experienced a delay in the initial diagnosis.

—Mary Carpenter

Every Tuesday, well-being editor Mary Carpenter reports on health news you can use.

I found this article very helpful….

Very good advice! Thank you!