iStock

HAVE TO sit for long periods—on planes, in meetings? Get up often and walk around. In between, don’t cross your legs and do foot exercises. Raise and lower the heels on both feet and then the toes. Drink water and wear loose-fitting clothes. For many people, compression socks can help.

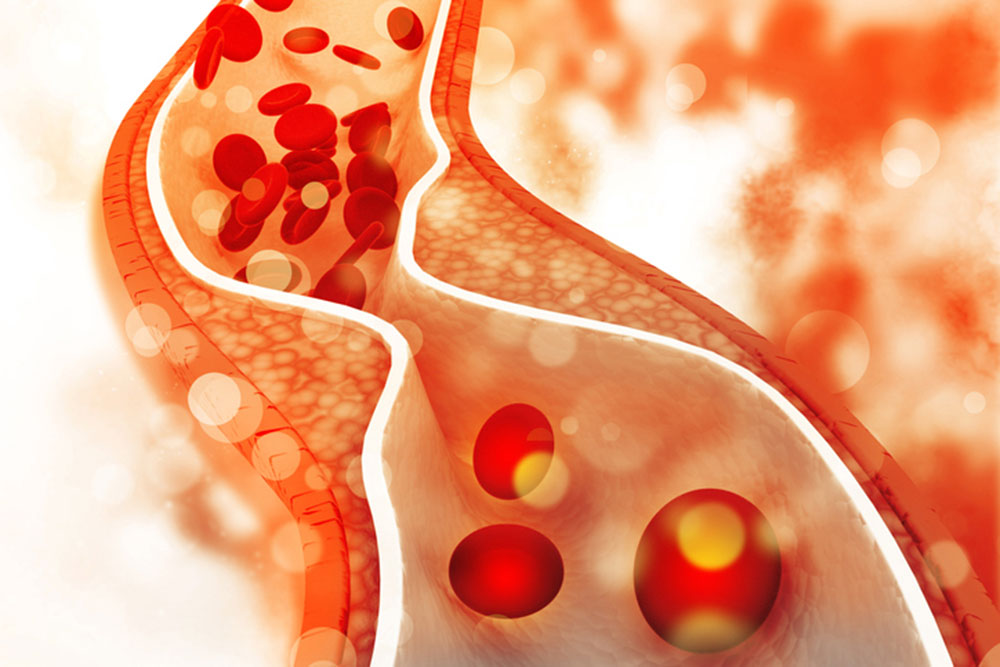

What you’re trying to avoid is deep vein thrombosis (DVT), clumping or clotting of the blood cells that can occur when blood moves too slowly through veins, most often in the legs. Over time, a clot in the legs can cause chronic swelling and pain, and cellulitis, a skin infection.

But the biggest risk comes from a clot that travels to the lungs where it can block blood flow and cause life-threatening pulmonary embolism (PE). However, PE occurs about 50% of the time with no symptoms. Signs include sudden shortness of breath, lightheadedness, chest pain and a rapid pulse.

DVT rates rise with age, increasing after age 45 from 1/1,000 to 5 to 6/1,000 people by age 80. In addition to prolonged immobility (standing, sitting and bed rest), DVT is more likely after injury or surgery that damages blood vessels.

“When we walk, our muscles contract and push the blood back to the heart,” explains Baton Rouge vascular surgeon Andrew Olinde. “Usually it’s a predisposing factor that caused you to get [DVT]—you had surgery or were immobile. Once active again, the risk of getting DVT again is low.”

DVT is also linked to hormone replacement therapy that includes estrogen and to low vitamin D levels. It occurs more often with obesity, with a family history of DVT or clotting disorders, and with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and cancer.

In athletes, especially endurance runners, DVT symptoms are likely to include bruises and stabbing Charley-horse pain. Exercise, on the other hand, lowers the risk of blood clots, especially in those who must sit for hours.

The clearest signs of DVT occur in only one leg: persistent swelling; feeling of warmth in the leg; red, blue or otherwise-discolored skin especially below the back of the knee; and pain that feels like cramping, soreness or ache, more likely during standing or walking, and often occurring in the back of the calf—rather than on the outside where injured muscles cause pain.

DVT symptoms get worse over time, rather than dissipate as they would with a pulled muscle, even after the leg has been elevated.

When a clot is suspected, the affected leg is checked for pain and swelling as well as for knots that are sometimes felt with a clot. Ultrasound can diagnose DVT and show if clots are in the deep, larger veins, where they are more dangerous than those in superficial veins.

DVT is usually treated with blood thinners, such as heparin or warfarin, for up to six months. An alternative, a tiny filter inserted in the inferior vena cava—the largest vein in the body —can catch a large clot before it reaches the lungs. In the case of severe symptoms, clot-dissolving medications can help—sometimes in combination with a balloon-catheter procedure called isolated thrombolysis.

Compression socks or stockings that are tight at the ankle and looser toward the knees help push the blood upwards, against gravity, to prevent pooling in the veins. The socks can also improve the flow of lymph to help reduce swelling. In healthy people, they can keep legs feeling warmer on airplanes and offer relief for leg fatigue.

Doctors recommend compression socks after surgery as well as for those who take estrogen or have a family history of DVT. And people who must sit for long periods find them helpful. But their promotion to prevent symptoms in people with an acute DVT lacks evidence—as does their use by athletes to improve performance. However, there is some evidence showing that the socks speed recovery and reduce soreness following a workout.

Those with peripheral neuropathy might have trouble feeling when compression socks are too tight and could impede circulation. In cases of peripheral artery disease (narrowing of the arteries that can cause pain when walking), the socks can interfere with oxygen delivery in arteries with impaired blood flow. Certain skin conditions or infections can also react badly to the socks.

The best recommended choices on Amazon have the highest compression rating—20 mmHg and above, considered “medical-grade”—and are touted to improve blood flow for upping athletic performance and promoted as combinations like “best stockings for running, medical, athletic”… as well as “best graduated athletic fit running.” But at this pressure, the socks can feel too tight and leave red marks on the legs.

Healthy people and anyone sitting or standing for long hours should choose the lightest compression rating —under 15 mmHg—produced for medical suppliers in neutral colors, but also in fun designs by Dr. Motion, Different Touch and others (available at the Amazon link).

—Mary Carpenter

Every Tuesday in this space, well-being editor Mary Carpenter reports on health news that affects our everyday lives.

very helpful, as are all your columns!