iStock

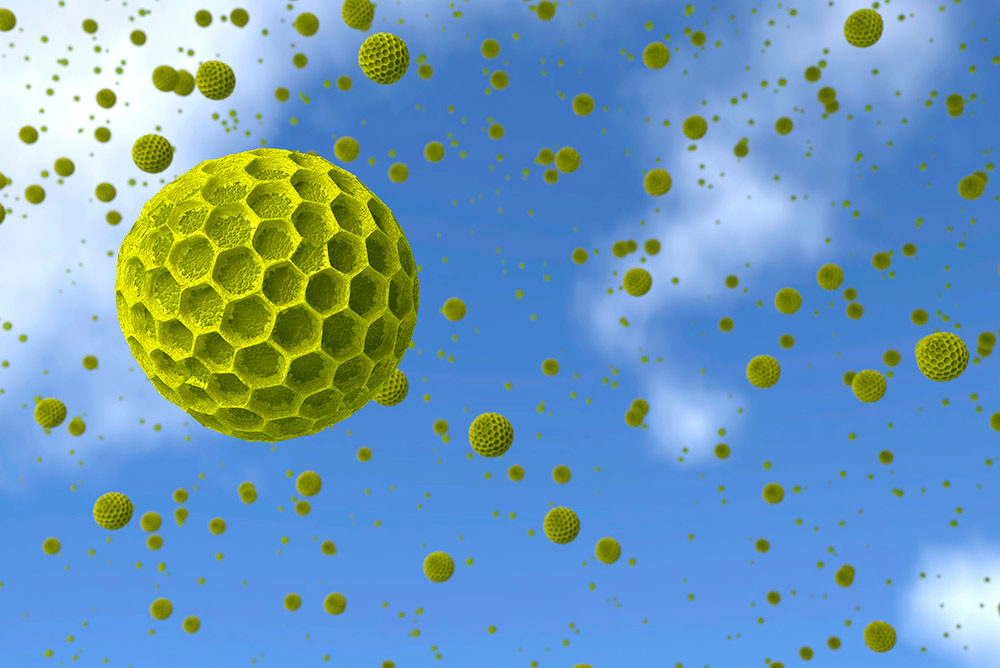

THE LIKELIHOOD of developing seasonal allergies (as distinguished from those to food, dust or other things) in the DC area is due to the sheer numbers of triggers here—with tree pollen starting off the spring season, grass pollen in the summer and weed pollen in early fall followed by leaf mold. U.S. Army microbiologist Susan Kosisky told the Washington Post, “We’ve got something for everybody here. . . . If you come to the Washington, DC, region without an allergy, there is a chance you will leave with one.”

In the allergy ranking of U.S. cities, numbers of allergenic grasses, trees and weeds are key variables, as are seasonal and other changes from year to year. According to Greer allergy maps, DC is near the top—with 14 grasses, 35 trees and 14 weeds, for a total of 62 seasonal triggers—falling between other notably allergenic cities of Houston at 58 and Knoxville at 64.

Being constructed on a swamp gives DC a comparably longer growing season with less likelihood of a killing frost to interrupt the season once it starts. Also, DC’s trees include many oaks, notorious for producing pollen that hangs around for a long time rather than dispersing quickly.

While each allergen has a yearly “crop,” some years it’s a bumper while others it’s mild,” explains Nutley, New Jersey, allergist Alan Goodman. Spotting the first green willows of springtime tells him when the office phone will start ringing. After 25 years in this specialty, he says: “I know it’s a bad season when the ringing phone never stops.”

Physical proximity to specific allergens is the only way to trigger seasonal allergies, which can develop following the first exposure over a two- to seven-year period. For one man who’d never had any allergies, it took three years after moving from Hong Kong to DC for seasonal allergies to become so severe that swollen tissues in his nose caused tiny blood vessels to break easily, resulting in frequent nosebleeds.

For some people, seasonal allergies that seem to arise anew in adulthood can be traced back to earlier sensitivities. I once put myself among new-to-DC allergy sufferers and then remembered having such bad poison ivy as a child that I wore gloves at night to keep from scratching.

Symptoms of allergic rhinitis—runny nose, sneezing, scratchy throat and itchy eyes—caused by seasonal triggers can be distinguished from those of colds and flu primarily by patterns of occurrence: arising during specific seasons, worsening after time spent outdoors and improving after nights with the windows shut. Symptoms particular to allergies include itchy eyes, absence of fever and clarity of the mucus.

Colds, by contrast, usually worsen over time and then improve; produce yellowish mucus; and can be accompanied by fever. And fever above 102 can indicate flu. Difficulty swallowing suggests strep throat, which requires a test because treatment includes antibiotics. Fatigue is common to all of these. But diagnosis can be tricky if something else occurs at the same time as an allergic reaction.

Allergy symptoms appear to be increasing around the world. Some blame higher concentrations of airborne pollutants. Others subscribe to the “hygiene hypothesis,” that life in developed countries became so sanitized that people’s immune systems didn’t develop correctly. The theory is controversial because greater use of antibiotics and indoor plumbing occurred in the same period. The good news: Immune responses weaken with age, making seasonal allergies less likely to arise in a person’s 30s and 40s, and especially after age 50.

Another villain is increasingly long pollen seasons caused by effects of global warming, such as rising temperatures and greenhouse gases. Research on the length of ragweed pollen seasons from 1995 to 2009 found that, compared with almost no increase in the three southernmost cities (in Arkansas, Oklahoma and Texas), seasons lengthened in Nebraska, Wisconsin and Minnesota cities by 11, 12 and 16 days, respectively, with a 27-day gain in the northernmost city in Canada. Though not included in this study, DC is closest in latitude to Nebraska.

Shorter springs—when spring arrives late—compress the allergy season, so that trees are pollinated later but more quickly, and grass pollen comes toward the end of that with no break. In what some call a “pollen tsunami,” peak DMV pollen concentrations can reach 4,000 particles per cubic meter of air.

For an individual to develop new seasonal allergic responses, the immune system must first identify as harmful such allergens as pollen and mold. In response, inflammatory chemicals such as histamine are released, causing symptoms that involve the nose, eyes, skin and digestive system.

Genetics affect an individual’s chances of developing allergies: Responses to the same allergens occur in 70% of identical twins and 40% of fraternal twins. Allergic parents are more likely to have allergic children, and those children are likely to have more severe allergies. What experts don’t entirely understand, however, is why someone develops an allergic reaction to certain allergens but not to others.

To combat allergy symptoms, the best non-sedating antihistamines for many sufferers are Claritin and Allegra, according to allergist Goodman, who advises patients to go for the cheapest available—as low as $12 per year at Costco. While some combination drugs include “decongestants,” those do not target the allergic reaction–which antihistamines do–and can cause side effects including blood-pressure problems and insomnia.

Even with medication, some patients spend weeks in the hospital, including days in the ICU. For the worst cases, “immunotherapy” using injections of specific allergens can alleviate or end symptoms. Extremely time-consuming—with regular shots starting at once a week and lasting over several years—and expensive, however, immunotherapy is usually worthwhile only for the most seriously afflicted.

Good weapons for most seasonal sufferers involve limiting exposure. If grass is the problem, don’t mow or, if you must, use a mask. After being outdoors, take a shower and throw clothes in the wash. Keep the windows closed. Best of all, if possible: Get out of town for the worst periods, and don’t come home until they’re over.

— Mary Carpenter