Photo by Celeste Duffy / iStock

OMEGA-3 FATTY ACIDS have been touted for a wide range of benefits—many traceable to reducing inflammation—for conditions that include cancer, mood disorders, arthritis and dementia. To date, the most impressive data concerns heart disease: a 2016 meta-analysis of data from almost 46,000 participants in 19 trials in 16 countries found increased omega-3 levels in the body’s cells associated with a lower incidence of fatal coronary heart disease.

Questions concerning omega-3s remain, however, about how much is enough and the best way to get that. Omega-3s in diet—from familiar sources including fatty fish like salmon and green leafy vegetables like spinach—are more “bio-available” than that from supplements, though adding these can help.

But when focusing on diet, the most important consideration is not simply increasing omega-3 consumption by eating greens, fish and grass-fed animals, but being vigilant about the ratio of omega 3s to omega 6s—the two major classes of polyunsaturated fatty acids.

“Omega-3s and omega-6s compete for positions in our cells,” according to Susan Allport in “The Queen of Fats: Why Omega-3s Were Removed from the Western Diet and What We Can Do to Replace Them.” Thus, a diet rich in omega-6s means that fewer omega 3s can be absorbed—even when eating fish for every meal.

Anthropological evidence suggests that the ratio during much of human evolution was closer to 1:1, according to neurobiologist Stephan Guyenet, author of “The Hungry Brain: Outsmarting the Instincts That Make Us Overeat,” who has studied ratios in non-industrial populations.

While a healthy balance might be closer to 4:1, Americans consume about 10 times as much omega-6 as they do omega-3—in processed foods, in farmed fish fed corn and soy, and in all hydrogenated oils.

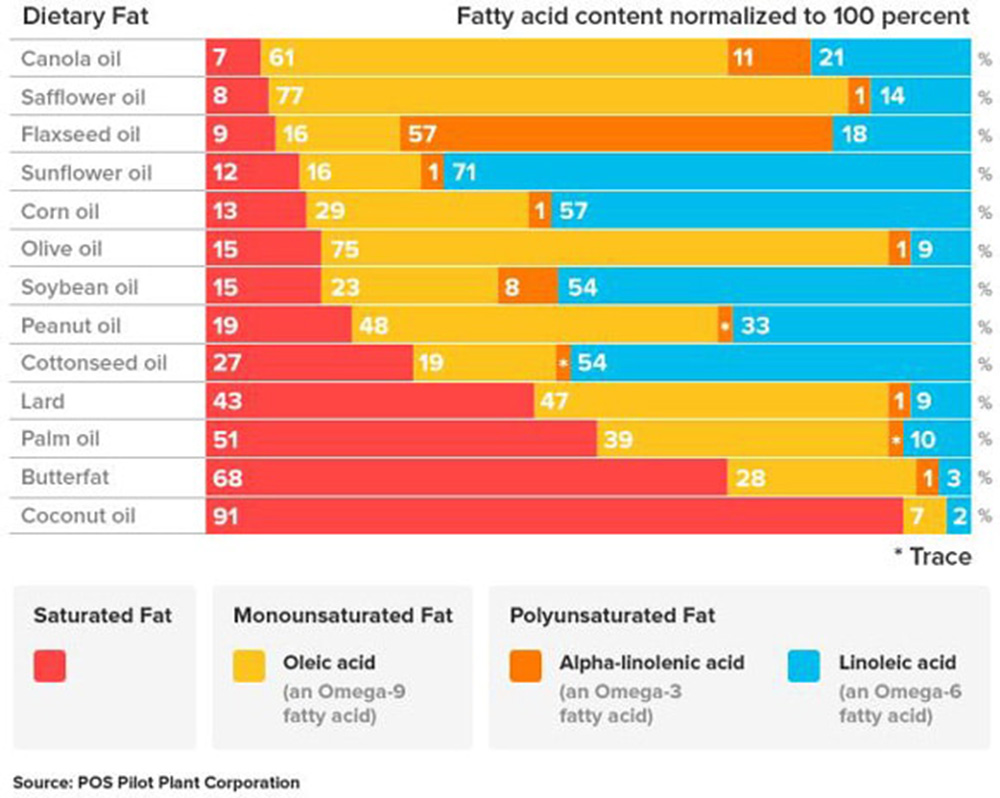

Reducing consumption of those pesky omega 6s requires limiting processed foods—specifically the oils used in those foods (see chart). The worst ratio is found in corn oil: 1% omega-3s (alpha-linolenic acid) to 57% omega-6s (linoleic acid). Oils considered “neutral” —with negligible effect either way on the body’s consumption ratio—are olive oil (1% to 9%), and coconut (7% to 2%).

Oils with the “healthiest balance”—that can be used to improve one’s daily ratio—are canola (11% to 21%) and flaxseed oil (57% to 18%). Allport adds flax to her food whenever possible: flaxseed oil along with olive oil in salad dressing; and ground flax seed to oatmeal or any cereal with insufficient omega-3s, and to replace up to one-quarter of the flour used in baking.

The best-balanced foods are meat, poultry and fish that are raised or farmed on grass or vegetable-based diets instead of corn; the dairy products, especially butter, that come from those cows; and the eggs that come from that poultry.

Allport recommends finding an egg “whose taste you enjoy” with as close to 300 milligrams of omega-3s and/or 100 milligrams of DHA as you can afford. Eggs from chickens fed a diet of corn and soy might have as little as 18 mg of DHA. (Key omega-3 fatty acids are DHA and EPA.) Because all eggs have some omega-3s, Allport warns: “Don’t be fooled by those…that don’t have more than 200 mg omega-3s/egg.”

Two high-level omega-3 brands are Christopher Eggs and Meijer Brand eggs with 660 mg. per egg (100 mg. of EPA and DHA)—as much as 13 times more than that of regular eggs. To show the power of one good egg, the comparative amount of omega-3s in eight ounces of one DHA-fortified “organic” milk is 32 mg.

While grass-fed products are usually more expensive, Allport believes the difference is more than made up in lower medical bills. By careful eating, she can keep the ratio of omega-6s and omega-3s in her tissues at a good level without the help of supplements. (Anyone wanting to know their personal ratio numbers can have their tissue levels of omega-3s and -6s evaluated, although such assessments reflect only recent dietary intake.)

For many people, however, even those working hard to reduce dietary omega-6, omega-3 supplements can make a difference. Supplements made from fish or krill are the most popular but have potential drawbacks: containing impurities (PCBs from plastics) and heavy metals; causing overfishing; and risking oxidation during production or shipping that can destroy healthy omega 3s.

While levels of impurities are considered too low to affect the general population, supplements made from algae avoid these risks and are a good option for several groups including pregnant women and infants (in formula), anyone taking large quantities of supplements—such as anyone with a recent head injury, and anyone who is especially concerned about contaminants.

While using flax seed and oil can help create a better balance, these products need to be kept cool and must be discarded at the first hint of rancidity; also, some people object to the taste.

Those of us not ready for supplements or added flax can keep making an effort to eat less processed food and more fish and leafy greens, and to follow any of the multitude of other suggestions—exercise, stress-reduction, diet, more exercise—with the goal of improving brain and body health.

—Mary Carpenter

To read more well-being posts, click here.