iStock

DISCOVERING THAT the same drug targeted at halting osteoporosis—with its increased risk of broken bones—can over time cause those same bones to break serves as a warning: wait before starting a newly approved drug—for 10 years or longer if possible. Consider the case of osteoporosis drug Fosamax.

Since its introduction in 1995, Fosamax has been snowballing side effects, many resulting in warnings from the FDA. The biggest risk appears to be “low-energy” or “stress” fractures” to the thighbone. Femur fractures can occur as a result of low-impact force—a fall from standing height or less—or sometimes as little as turning the body the wrong way, stopping the car suddenly or simply walking.

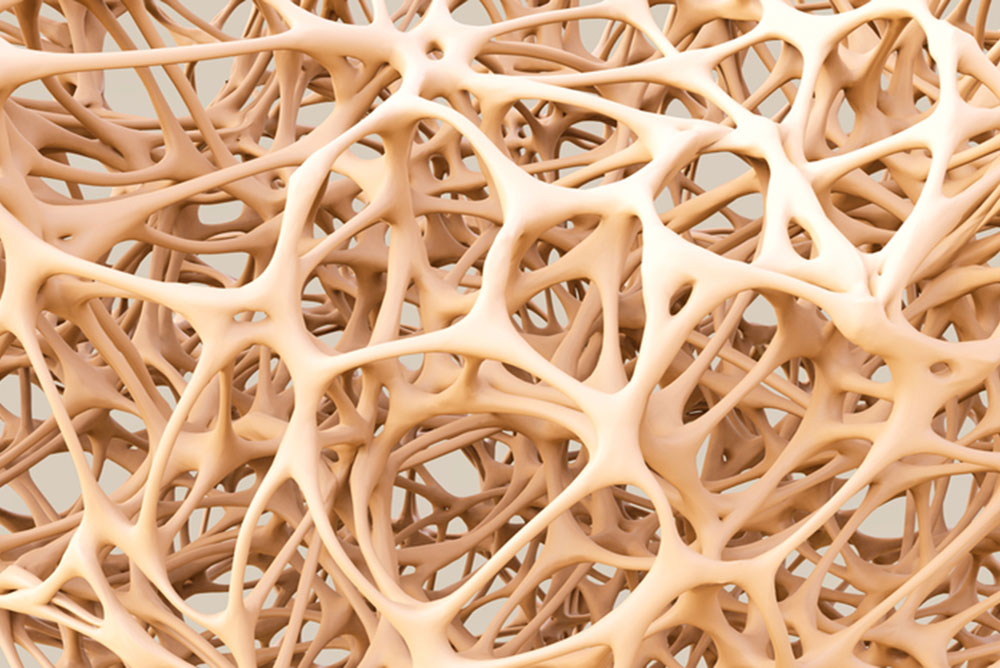

The bisphosphate Fosamax works to increase bone density by slowing the body’s natural process of bone breakdown and resorption. It was the first drug on the market to slow bone loss, which can lead to crippling fractures of the hip and spine.

How the drug causes femur fractures is still unclear. It kills cells designed to remove old bone, with the result that there might be too little room for new bone growth. The drug could also interfere with the repair of microscopic cracks caused by normal wear and tear, and then microdamage accumulates over time to cause fractures.

Or Fosamax could cause bones to become more brittle and thus less resistant to wear and tear, perhaps in the process of slowing bone turnover or as it suppresses bone breakdown with ongoing mineralization of the bone. Finally, the active ingredient in Fosamax, alendronate, may slow the development of new collagen, found in abundance in bones.

In the drug’s first year, the FDA warned the manufacturer Merck of overstating its benefits and minimizing its risks. Within several years of approval came the first reports of femur fracture. But not until 2008 did a study in Singapore report on 17 women—average age of 66, average length of time on Fosamax of five years—who had femur fractures without major trauma. Of these, 13 had leg pain before the fracture occurred.

A subsequent study at New York’s Hospital for Special Surgery, found that of 25 patients taking Fosamax, 20 had a femur fracture and 19 of these occurred in patients taking Fosamax the longest. More problems arose when physicians began prescribing Fosamax for osteopenia, a slight thinning of the bones that can precede osteoporosis—which previously had been untreated, and which many physicians consider insufficiently worrisome to require any treatment at all (see MyLittleBird story on osteopenia).

While a 2008 Harvard Health Letter concluded that “most experts believe that when Fosamax is used appropriately, its benefits greatly outweigh the risks,” by 2014 the Harvard Letter suggested that most women should consider taking a “bisphosphonate drug holiday” after three to five years.

Meanwhile as early as 2004, Fosamax was linked to “Dead Jaw Syndrome” (osteonecrosis of the jaw) that can eventually cause the jawbone to collapse completely. Although the cause is still being investigated, patients are urged to consider having dental surgery before starting Fosamax—that is, when such surgery can be anticipated. Fosamax-related lawsuits against Merck were filed beginning in 2004.

In 2008, the drug was linked to esophageal cancer. In addition, Foxamax has caused burning in the esophagus as well as “incapacitating bone, joint and muscle pain,” according to the Drugwatch.com report.

In 2010, the FDA required labels warning about the risk of thighbone fractures. Currently, an FDA advisory committee wants to limit the amount of time a patient takes Fosamax but has not yet come up with a specific limit. In addition, the WHO has developed a scale to help determine which osteopenia patients might benefit from the drug.

Because it takes about 10 years for bisphosphonates stored in the body to decline by half, the recommendation for those taking a “drug holiday” is to test bone health every two years after stopping the drug. In one study, women who had taken Fosamax for at least five years were divided into two groups, one continuing the drug and the other taking a placebo. After five years of the study, the rate of hip fractures—considered “a far more serious injury” compared to fractures of the spine or femur—was the same for both groups.

On the other hand, those at highest risk of hip fracture—those who’ve had a fracture in the past and had low bone density when starting therapy—might benefit more from continuing the drug compared to the risks of a drug holiday. But try telling that to someone who has suffered a femur break—unexpected, with little provocation—after taking Fosamax: most of these women want nothing more to do with the drug.

—Mary Carpenter

See more Well-Being posts here.

It amazes me that the drug which is supposed to build bone actually does the opposite. Just took myself off Fosomax, and will be trying something else. But my use was very short term, and my side effects annoying enough to ask for something else. Thank goodness no femur fractures, but not on it long enough. I hope.

I’ve been taking it about 6 months, on and off, mostly off. Is there a better drug or do all of them (Actonel, etc.) have similar effects? So crazy-making.

Sadly, I should refer you to your doctor for that. For some people, the risk of serious fracture is enough to warrant taking the drug — femur fractures being considered less serious that those of the hip and spine. Just watch out, try not to fall. And remember that femur fractures, though painful, actually heal quite well and fast. Still, I personally would stop the drug if at all possible…