iStock

AROUND THE TURN of the last century, it was a trend: If you lacked energy or felt blue, try giving your thyroid a boost. When a psychiatrist I saw one time asked me about dry skin, dry hair and a few disagreeable digestive issues, I said, yes — all my life — and she right away prescribed “thyroid pills,” synthetic thyroid hormone. Within weeks I felt so jumpy and distracted in the mornings that I tossed the pills. Now people are shocked if I mention receiving the Rx without prior blood testing.

Before thyroid medication is prescribed, blood levels of thyroid hormone should be checked and then rechecked every four to eight weeks to fine-tune the dose — depending on health, weight and how an individual’s blood absorbs the hormone. Although there is a “normal” target range for thyroid-stimulating hormone (which incites the thyroid gland to produce more), each person’s range varies depending on their health.

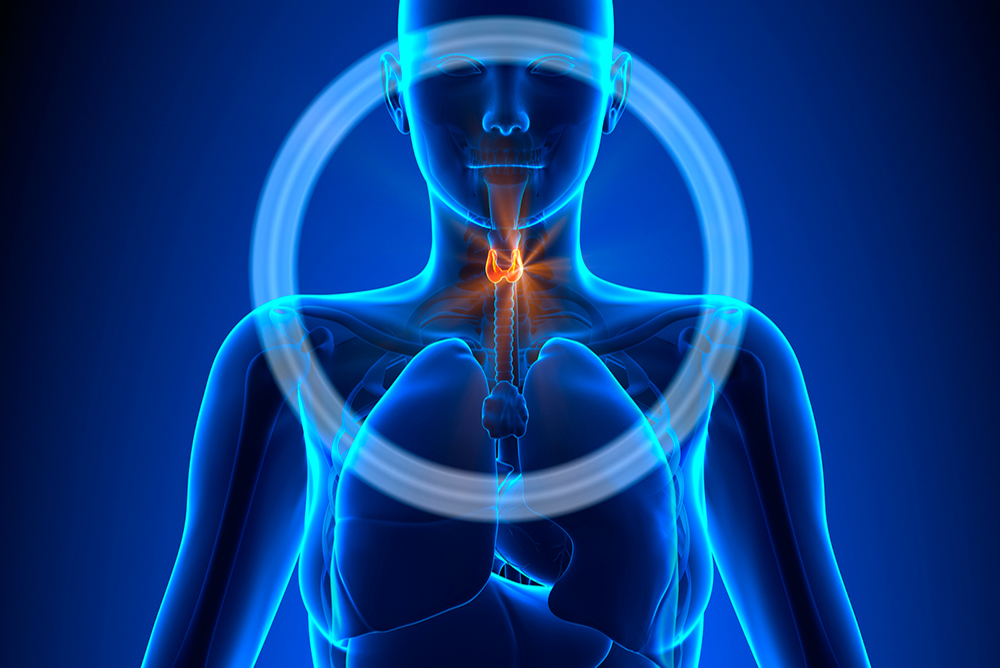

The thyroid gland, shaped like a butterfly and located at the base of the neck, extracts iodine from food, notably salt, and converts it into the two thyroid hormones that control metabolism and thus affect every cell in the body. Directed by the pituitary gland, which is in turn regulated by the hypothalamus, the thyroid gland has so many different functions that fiddling with its operations produces an array of desirable and undesirable effects.

Hyperthyroidism — actually caused by excessive thyroid supplements as well as when overgrowth of normal thyroid tissue or thyroid nodules produce too much hormone — can lead to anxiety, nervous energy, irritable feelings and difficulty concentrating, as well as hunger, thirst, weight gain or loss and flu-like aches and pains. Hyperthyroidism can be apparent in a slight tremor of extended fingers, overactive reflexes and warm, moist skin. Its risks include heart arrhythmia and osteoporosis.

The opposite condition, hypothyroidism, results when too little thyroid hormone is circulating in the blood, often caused by Hashimoto’s disease, an autoimmune condition that leads to swelling of the thyroid gland and reduced production of thyroid hormone. In addition, particularly in those for whom low thyroid runs in the family, stress raises cortisol levels that can both interfere with thyroid production and increase vulnerability to Hashimoto’s.

Because hypothyroidism can exist at the same time as depression, and the two conditions share so many symptoms, it can be hard to tell what’s causing what. Also, hypothyroidism itself can cause feelings of depression. Common symptoms of both include fatigue, sleeping too much, sluggishness and trouble concentrating — yes, the same trouble caused by hyperthyroidism. For a person who feels depressed and also has low blood levels of thyroid hormones, thyroid-replacement medication can improve both conditions.

Thyroid nodules are present in up to 50% of the population, but most cannot be seen and only around 5% can be felt at all. Several nodules that cluster in an enlarged thyroid gland, called a goiter, can arise with no cause or from consuming too little iodine.

D.C.headhunter Jo T. first discovered two of these swellings the day she turned 50 in a yoga class, when they caused her to “choke/cough a bit” in the downward-facing dog pose. Over the years, she experiences symptoms only in the down-dog position, and these go away when she gets out of the pose. Based on regular ultrasounds, her doc determines the swellings are benign and advises doing nothing unless serious difficulties arise. Surgery to remove goiters risks damaging the nearby vocal chords.

Thyroid nodules should be evaluated by a doctor — because there is a small risk of malignancy, especially if the nodule is large, hard and causes pain — using ultrasound and/or biopsy. Those who received ionizing radiation treatments in the head and neck area, used during the first half of the 20th century for common complaints like acne, are more likely to develop thyroid nodules.

Some foods contain compounds that make it more difficult for the thyroid gland to produce hormones, including soy, peanuts, strawberries, broccoli, kale and other vegetables — although steaming vegetables can break down the goitrogenic compounds. Iodine is plentiful in dairy products and eggs, shellfish, seaweed and fish from the sea, and meat and some breads, as well as in about half of the multivitamins available in the U.S.

Iodized salt contains about 400 mcg (micrograms) of iodine per teaspoon, with the RDA (Recommended Dietary Allowance) for adults set at 150 mcg per day. Before iodine was added to salt, the greatest risk of thyroid deficiency existed among people living far from the ocean where there is less iodine in the soil, such as in the Midwest and Great Lakes —at one time dubbed the “goiter belt.” As people consume less salt, those closer to the ocean fare better: for women in the DMV, higher iodine levels in soil are the great protector.

— Mary Carpenter

Mary is the Well-Being Editor of MyLittleBird. Read more about Mary here.

Her last post was about hearing loss.