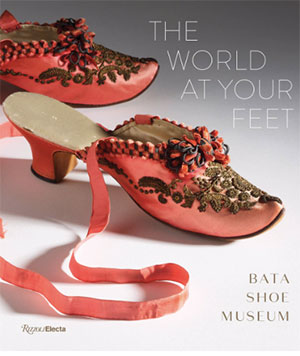

Marking its 25th anniversary, the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto has a new book out, The World at Your Feet. featuring more than 100 of the museum’s most beautiful and important pieces of footwear.

WEARING SHOES is not always fun. Shopping for them is better. But best of all is looking at them: That’s pure delight.

Which is why I’ve been meaning for years to go to Toronto to visit the Bata Shoe Museum. And now, thanks to technology, at least parts of the museum can come to me.

Now in its 25th year, the museum—BSM to its friends—stems from the inspiration, even obsession, of one woman, Sonja Bata. Sonja Bata didn’t create the Bata shoe company—she married into the Czechoslovakian institution when in 1946 she wed the son and successor of the founder, Thomas Bata. But she embraced it, traveling the world with her husband spreading the word of the company’s prodigious output.

The Depression was bad for the company and its workers, World War II was devastating, and post-war nationalization of the factories and retail outlets by the Soviet-controlled Communist government hammered the proverbial nail into the coffin of what had been a global enterprise. The Batas cast about for a new home for the assets they still controlled and were welcomed by Canada.

In her Canadian life, while Sonja Bata was working and traveling with her husband, she was also scouting the world for historical and exotic footwear, material that created her world-class collection of shoes—and eventually gave rise to the museum, with its 14,000 (and counting) shoes and related artifacts covering some 4,500 years of footwear history. Bata died in 2018.

After the 2020 pandemic shutdown, BSM reopened to the public in mid-July, with limited admission and Covid protocols. Its newest exhibition echoes Sonja Bata’s working principle: Every shoe has a story. The Great Divide: Footwear in the Age of Enlightenment explores the ways in which 18th-century footwear reflected the competing philosophies of just who had “natural,” inborn human rights, covering imperialism, sexism, racism—themes that may seem just a bit familiar to 21st-century museum-goers.

The BSM website also has online exhibitions. All About Shoes provides a deep dive into Canada’s aboriginal groups (“Northern Athapaskan Footwear,” anyone?). A bit more commercial is Standing Tall: The Curious History of Men in Heels.

Poking around the site you learn interesting factoids, such as that women’s gold and silver evening shoes were a big trend during the Great Depression not because they made women feel rich but because, fashion editors advised, either could be worn with any color of evening ensemble (assuming, I guess, you had more than one evening ensemble). And I learned that the original purpose of putting women in high heels was to make their feet look daintier, especially when peeking out from beneath voluminous skirts. There’s a touch of celeb stuff—John Lennon’s Beatle boots, Elton John’s sparkly platforms. And everywhere, serious and less so, is, to mix body parts, terrific eye candy.

—Nancy McKeon

According to the online exhibit Standing Tall, this small French or English shoe dates to the middle of the 17th century and was most likely made for a well-to-do boy. The fact that the wearer was male is suggested by the shape and type of heel. Stacked leather “polony heels” were popular on men’s footwear at this time. That the child was well-off is indicated by the height of the heel; its marked impracticality helped to declare the wearer’s privilege. The heel is also painted red in keeping with the fashion of the day. / Bata Shoe Museum Toronto.

These are Italian women’s heels from between 1660 and 1700. As the 17th century wore on, the type of heels on men’s footwear expressed two distinctly different forms of masculinity, the refined man of elegance and the man of action. Leather-covered heels came to be worn by men at home or formal settings while stacked leather heels were common on men’s riding boots and other plain, hardworking footwear. Women’s fashion favored covered heels and although clear formal differences emerged between men’s and women’s heels—men’s grew high and were sturdy while women’s tapered to increasingly narrow points—by the middle of the century, the covered heel smacked of refinement, a feature that would eventually damn it in men’s fashion. The stacked leather heel, however, would live on as a signifier of rugged masculinity. / From Standing Tall, Bata Shoe Museum Toronto.

When the Beatles became popular in the early 1960s, they stood at the forefront of the Peacock Revolution, a movement in men’s fashion that sought to reclaim the privilege of extravagant dress. Their signature look included “mop-top” hair, tight-fitting suits, and the now- famous “Beatle boot.” These boots were typical Chelsea boots popular in men’s fashion since the 19th century with the exception that they featured a significantly higher heel, borrowed from male flamenco dancers. This boot was worn by John Lennon. / From Standing Tall, Bata Shoe Museum Toronto.

1970s musicians like Elton John strutted on stage in outrageous outfits and glittering high heels. This pair of stage-worn shoes feature heels reaching 7.5 inches in height. This was made possible by the addition of 5-inch-thick platforms under the forepart of the foot. In the 1970s, men favored footwear with distinct heels rather than shoes with solid platforms, which in the history of Western fashion have always been feminine. These shoes were worn by Elton John. / From Standing Tall, Bata Shoe Museum.

The Enlightenment was characterized by competing claims for human rights, i.e., who was really worthy of them. The school of thought embodied in this shoe is that, really, only European men, and only men of wealth, could truly be said to have “natural” rights. The English shoe from between 1760 and 1780 has a low heel, at that time confirming that it’s a man’s shoe, sumptuous fabric signaling wealth and and an extravagant pink bow. The Great Divide exhibit points out that pink was not a particularly feminine color in that era. / From The Great Divide, Bata Shoe Museum Toronto.

This 18th-century Indian-English shoe, from the Great Divide exhibit, shows a traditional upper-class Indian jutti, a flat shoe, here extravagantly embroidered (including iridescent sequins made from beetle-wings!) that has been made into an Englishwoman’s pump by removing the jutti sole and replacing it with a leather sole and a heel. / From The Great Divide, Bata Shoe Museum Toronto.

In 1790s America, the newborn nation sought to make its own goods. This Boston shoe is flat because by that time heels had become associated with aristocratic excess. / From The Great Divide, Bata Shoe Museum Toronto.

The Bata Shoe Museum is an extravaganza in its own right, with temporary exhibits complementing the extensive permanent collection of shoes and associated artifacts. / Bata Shoe Museum Toronto.

MyLittleBird often includes links to products we write about. Our editorial choices are made independently; however, a purchase made through such a link can sometimes result in MyLittleBird receiving a commission on the sale, whether through a retailer, an online store or Amazon.com.