By Nancy Pollard

After owning one of the best cooking stores in the US for 47 years—La Cuisine: The Cook’s Resource in Alexandria, Virginia—Nancy Pollard writes Kitchen Detail, a blog about food in all its aspects—recipes, film, books, travel, superior sources, and food-related issues.

A POST on blackberries a couple of years ago pulled up an intriguing story about Luther Burbank, a name I remember vaguely from plant and seed catalogues that were regularly sent to my mother. She loved zinnias and Shasta daisies for her backyard garden, and whether she knew it or not, she was in debt to Luther Burbank. He was the genius who made zinnias the perfect flower for August gardens, and he crossbred several types of daisies to create the Shasta, which he named after Mount Shasta in the Cascade Mountain Range in California, because the petals had the color of pure snow. Apparently, the Shasta is the most widely grown daisy in the world. And Burbank also introduced the Himalayan Blackberry to the Northwest, which, while bountiful in harvests, is also a plague.

A POST on blackberries a couple of years ago pulled up an intriguing story about Luther Burbank, a name I remember vaguely from plant and seed catalogues that were regularly sent to my mother. She loved zinnias and Shasta daisies for her backyard garden, and whether she knew it or not, she was in debt to Luther Burbank. He was the genius who made zinnias the perfect flower for August gardens, and he crossbred several types of daisies to create the Shasta, which he named after Mount Shasta in the Cascade Mountain Range in California, because the petals had the color of pure snow. Apparently, the Shasta is the most widely grown daisy in the world. And Burbank also introduced the Himalayan Blackberry to the Northwest, which, while bountiful in harvests, is also a plague.

An Armenian From India

Himalayan blackberry bramble gone wild (and invasive). / Photo from the Invasive Species Council of Metro Vancouver.

A story written by Ann Dornfeld for NPR outlines the dramatic changes wrought by industrialization, the cross-country penetration of the railroad, and the introduction of the lightbulb and the Model T. With these converging influences, a new middle class emerged in the US, centered around industrial hubs, with a commensurate desire for access to fruits and vegetables. Luther Burbank had only a high school education but had inherited a passion for gardening from his mother. He took the profits from his hybrid potato (now named Burbank) and bought a small farm in Santa Rosa, California. He crossbred endlessly to produce fruits and vegetables that could not only withstand transcontinental shipping but also succeed in the new middle class’s smaller urban gardens. As with his effort to create a spineless cactus for cattle forage, Burbank wanted to create a thornless blackberry. He traded packets of seeds with collectors across the globe and was sent a packet of blackberry seeds from a collector in India. The berry was sensational in flavor and size—and was originally grown in Armenia. He tinkered and gave it the name of Himalaya Giant (now known as the Himalayan Giant). It went into his gardening circular with the proviso that it was perfect for gardens in mild climates. Puget Sound and the surrounding areas filled the bill.

Today, according to a noxious-weed expert in Washington State, this particular blackberry grows everywhere, dry or wet soil, forests and fields, crowding out any native plant in its way. And the seeds, spread by birds, can lie underground for years before germinating and, as with any creeper, wherever its cane touches the ground, a new plant is born.

Crowning Creations, Theories & Frites

Luther Burbank had a genius for developing plants and produce that the public craved (think freestone peach, plumcot, nectarine, and of course the Russet Burbank potato). Others were more forgettable, such as his cross between the potato and tomato, the pomato. I should also mention his genius in creating seductive mail-order catalogues and even developing specialized mailing lists. From Burbank’s more than 800 new strains of vegetables, flowers, and fruits, the Russet Burbank is the most widely grown potato around the world. He developed it as a solution to the Irish Potato Famine, in which the potatoes died from Late Blight not only in Ireland but across Europe as well. Ironically, he could not patent this marvelous hybrid , as patents on tubers were not allowed in the US.

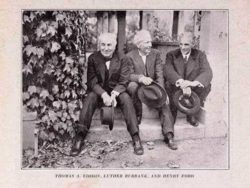

Thomas A. Edison, Luther Burbank, and Henry Ford, three men who helped to engineer the modern world. / Photo from the New York Botanical Garden/LuEsther T. Mertz Library/Biodiversity Heritage Library.

I look at this photo of Luther Burbank, flanked by Thomas Edison and Henry Ford, and think that they were perhaps a bit like Bill Gates, Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg, who changed our lives in the 21st century. Like these modern titans, they too were flawed in their obsession with their genius. In Burbank’s case, he became convinced that, like his plants, human characteristics could be bred and shaped by altered environments. So it was not surprising that he joined the Eugenics movement in the US and even wrote a book titled The Training of the Human Plant. Regrettably, he ignored the scientific treatises of Mendel and theorized about human selective breeding.

That said, I still think that my favorite potato for making frites will remain the Russet Burbank. I sort of follow the rules of chef Daniel Boulud for prepping them. I must confess that my favorite frying fat is beef tallow (mixed sometimes with bacon grease or duck fat).

The basic process involves double-frying. I peel the potatoes, slice them on a mandoline and soak them, preferably overnight but at least several hours. You can drain and rinse again to remove more starch if you have time. I dry them thoroughly in a salad spinner or dish towel. I heat my fryer with my choice of fats to about 325F and cook the potatoes just until they form a slight crust, around three to six minutes, depending on the potato. Then I lay them out on a tray and refrigerate them if they are not going to have the second frying for a few hours. It is important, however, to bring them to room temperature before the final frying. Room-temperature fries will not lower the frying temperature too much, and your fries will have a crispier exterior.

The basic process involves double-frying. I peel the potatoes, slice them on a mandoline and soak them, preferably overnight but at least several hours. You can drain and rinse again to remove more starch if you have time. I dry them thoroughly in a salad spinner or dish towel. I heat my fryer with my choice of fats to about 325F and cook the potatoes just until they form a slight crust, around three to six minutes, depending on the potato. Then I lay them out on a tray and refrigerate them if they are not going to have the second frying for a few hours. It is important, however, to bring them to room temperature before the final frying. Room-temperature fries will not lower the frying temperature too much, and your fries will have a crispier exterior.

For the second round of frying, I prefer getting the frying fat up to 375F. It usually drops to 360F as you fry the potatoes. My Thermapen is once again my best friend here. The batches should turn golden after three to four minutes. Have a basket lined with a napkin, dish towel, or paper towels ready to serve to your very happy diners. You can use fleur de sel or Maldon salt for a final sprinkle. I love the additional garnish from Erin French’s Lost Kitchen Cookbook, which is a teaspoon of olive oil mixed with a large minced garlic clove, a teaspoon of fresh thyme and 2 teaspoons of dried Herbes de Provence. And then sprinkle liberally with Maldon salt—I use this mixture so frequently that I have a large tub on hand. French adds lavender flowers, which I liked, but this was nixed by another person in this house, so I have removed the offending buds in future editions. Right before serving, toss the fries in this mixture along with the salt of your choice and rush the basket to the table.

I judge a restaurant based on its French fries…. My favorite food group. I haven’t made them for years, used to bake frozen ones in the oven when kids were little. My son makes them in his turkey deep fryer at Thanksgiving, they are the BEST. Funny story, my father in law worked on the railroad and one time had a carload of frozen McDonalds fries in 20 # bags. The refrigeration broke and he brought home many bags for his freezer. We got one bag so went to Sears, bought a small deep frier and we liked them a lot! They were very very good! The only other thing I made in it was homemade donuts, only did that once–way too much work