By Nancy Pollard

After owning one of the best cooking stores in the US for 47 years—La Cuisine: The Cook’s Resource in Alexandria, Virginia—Nancy Pollard writes Kitchen Detail, a blog about food in all its aspects—recipes, film, books, travel, superior sources, and food-related issues.

GROWING UP in my family, you used margarine in cooking and baking and you reserved butter for the table. My parents’ generation believed that this, along with iceberg lettuce for salads, were good economies, as iceberg almost never wilted and the more expensive flavor of butter was lost in baking. Iceberg lettuce has never darkened my refrigerator’s crisper drawer, and I stopped buying margarine quite a few years ago. I’ve had a few heretical moments since when I wondered whether, in certain cases, it might be better than butter to cook with. Because margarine actually has more water than butter (80% fats to 16% water), baked goods last longer, have a chewier texture, some say are more tender, and in the case of pie crust, might be even flakier. But there is no arguing that margarine does lack the flavor punch of butter.

GROWING UP in my family, you used margarine in cooking and baking and you reserved butter for the table. My parents’ generation believed that this, along with iceberg lettuce for salads, were good economies, as iceberg almost never wilted and the more expensive flavor of butter was lost in baking. Iceberg lettuce has never darkened my refrigerator’s crisper drawer, and I stopped buying margarine quite a few years ago. I’ve had a few heretical moments since when I wondered whether, in certain cases, it might be better than butter to cook with. Because margarine actually has more water than butter (80% fats to 16% water), baked goods last longer, have a chewier texture, some say are more tender, and in the case of pie crust, might be even flakier. But there is no arguing that margarine does lack the flavor punch of butter.

An Army Marches on Margarine

Margarine has such a fraught history, too. Its first appearance arrived via a French chemist, Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès, in 1869. Napoleon III, in his ongoing battle with the German Kaiser, issued a decree and a reward for an inexpensive butter replacement for his army. Mège-Mouriès, who had previously patented a process to increase bread production, developed a method for churning beef tallow with water and milk. He named his patented invention “oleomargarine,” loosely coined from the Greek terms for olive oil and luster, a euphemism for the somewhat pearly look of his whitish-gray invention.

Even though this inexpensive fat was beneficial not only to the French military but also to the poorer classes in France, a penniless Mège-Mouriès had to sell his patent to a Dutch company. In a few years several companies were creating margarine as a cheap alternative to butter throughout Europe. At the same time, the profitability of selling tons of an inexpensive butter substitute caught the eye of American businesses. They produced a margarine by combining animal fats with vegetable oils, which became so popular that the dairy industries, primarily in Wisconsin, lobbied successfully for a law that placed heavy licensing fees and taxes on oleomargarine production in 1886. And some states with dairy-friendly legislatures banned the sale of margarine outright.

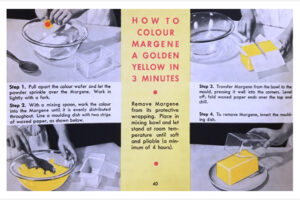

Two world wars, however, made oleomargarine production a necessity, and the battle between butter and oleo became one of color. The dairy industry employed several strategies to restrict margarine manufacturers from making their spread look like butter instead of lard. Restrictions were enforced to keep margarine from being dyed yellow at point of manufacture. At one point, the dairy industry forced margarine manufacturers to dye their product pink, a law that was finally struck down by the Supreme Court in 1898. In the 1940s, margarine manufacturers, realizing that their consumers really wanted this spread to look like butter, enclosed packets of yellow dye that you or your children kneaded into the whitish-grayish mass to make it look more like butter.

Two world wars, however, made oleomargarine production a necessity, and the battle between butter and oleo became one of color. The dairy industry employed several strategies to restrict margarine manufacturers from making their spread look like butter instead of lard. Restrictions were enforced to keep margarine from being dyed yellow at point of manufacture. At one point, the dairy industry forced margarine manufacturers to dye their product pink, a law that was finally struck down by the Supreme Court in 1898. In the 1940s, margarine manufacturers, realizing that their consumers really wanted this spread to look like butter, enclosed packets of yellow dye that you or your children kneaded into the whitish-grayish mass to make it look more like butter.

The H Word

Hydrogenation—where water and a plant oil could be chemically induced to create a solid fat—was a game changer. Beef tallow, which remained in short supply during two world wars, was no longer needed to be the base for this cheap butter substitute. In the US, the advance of this hydrogenated mixture of any vegetable oil zeroed in on readily available cottonseed oil. With the ability to chemically standardize the spread, hydrogenated margarine was more dependable than much of the butter offered in grocery stores. And of course, the burgeoning growth of the soybean and corn commodity crops increased production of this inexpensive ingredient as a breakfast spread and for cooking.

Hydrogenation—where water and a plant oil could be chemically induced to create a solid fat—was a game changer. Beef tallow, which remained in short supply during two world wars, was no longer needed to be the base for this cheap butter substitute. In the US, the advance of this hydrogenated mixture of any vegetable oil zeroed in on readily available cottonseed oil. With the ability to chemically standardize the spread, hydrogenated margarine was more dependable than much of the butter offered in grocery stores. And of course, the burgeoning growth of the soybean and corn commodity crops increased production of this inexpensive ingredient as a breakfast spread and for cooking.

It was not until 1990 that the link between increased heart disease and trans fats produced by hydrogenated margarine and other similar products was discovered.

The dairy industry, long a foe of the margarine industry, also had a health problem to counter. Already more expensive, by the 1960s, scientific articles began to appear demonstrating that products with animal fats contributed to heart disease. I remember my father (who did suffer from heart issues) berating a waiter in a restaurant for serving him whipped cream on a dessert. It really was not until about the mid-1990s that the evils of trans fats had enough scientific research and data to counteract the nation’s slavish devotion to non-animal fat and chemically enhanced spreads and food products. And it was not until 2018 that the FDA banned partially hydrogenated fats from food products.

Butter Is Not Better

Valeria Lishack is a Hungarian American pastry chef, and in the early years of La Cuisine had a wonderful little boutique bakery, The Poppy Seed. Many years later she worked at the shop, set clients straight on baking issues and ran some incredible baking classes in the shop space. She also made these delicious potato dumplings. Val married a Polish American, and their vows were made in a Ukrainian church in Pittsburgh. She adapted her recipe from the “church ladies” of this very Ukrainian parish. As in so many immigrant recipes (Italians substituted cottage cheese for ricotta, for example), three slices of American cheese were added to the potato mixture. Her daughter, Kat Tines, has this recipe memorized and carries on the tradition. Val swears that the inclusion of margarine in the dough made a better pierogi than butter. I cannot argue. These, with a little practice, and sautéed in some melted butter, are awfully good!

N.B., I do not have a pierogi-making bone in my body and love this tool.  Manufactured by Kuchenprofi in Germany, this stainless-steel dumpling/empanada tool is invaluable. It comes in three sizes. Here I use the one that is 4¼ inches in diameter. The underside acts as a cutter. You place the dough circle on the other side and fill it with a heaping tablespoon of the potato filling and press down firmly. I don’t wet the dough to seal it the way Kat Tines told me to; it wasn’t necessary for this dough, which is elastic enough to seal perfectly well without additional water. When re-rolling the leftover dough, wrap it in cling wrap and wait for half an hour. This dough is so stretchy that it springs back if the gluten isn’t relaxed enough for a second roll-out. You can fold over the pleated area if you are worried that the pierogi will open at the seam, but mine never do. Make a large batch and then freeze the rest for as long as three to four months.

Manufactured by Kuchenprofi in Germany, this stainless-steel dumpling/empanada tool is invaluable. It comes in three sizes. Here I use the one that is 4¼ inches in diameter. The underside acts as a cutter. You place the dough circle on the other side and fill it with a heaping tablespoon of the potato filling and press down firmly. I don’t wet the dough to seal it the way Kat Tines told me to; it wasn’t necessary for this dough, which is elastic enough to seal perfectly well without additional water. When re-rolling the leftover dough, wrap it in cling wrap and wait for half an hour. This dough is so stretchy that it springs back if the gluten isn’t relaxed enough for a second roll-out. You can fold over the pleated area if you are worried that the pierogi will open at the seam, but mine never do. Make a large batch and then freeze the rest for as long as three to four months.

Ukrainian American Potato Dumplings

- 4 ounces (113gr) margarine

- 1 cup (237ml) hot water

- Approximately 3 cups (360gr) all-purpose flour

- 1 teaspoon fine sea salt

- 1 egg

- 2½ pounds (1 kg+) red-skinned potatoes

- Optional additions

- ¾ cup (177ml) grated melting cheese

- 1 cup (237ml) diced sautéed onions OR

- or 1/3 (79ml) cup sour cream with the addition of chopped chives or dill

- Combine the margarine and water in a saucepan. Over low heat, melt the margarine in the water and allow to cool to lukewarm.

- Add about 2½ cups flour and the salt to a mixing bowl (reserving the rest of the flour for dusting the board and dough—you may use a bit more).

- Whisk the egg into the cooled margarine and water mixture.

- Pour this liquid into the flour and with a spatula or wood spoon pull the ingredients together to make a soft dough.

- Sprinkle the remaining flour on your counter and knead the dough for several minutes until it is smooth and soft.

- Wrap it thoroughly in cling wrap and chill in the fridge for at least an hour before rolling out.

- For the filling:

- Put the potatoes in a pan of cold salted water and bring to a low boil.

- Cook the potatoes in the skin until tender.

- Drain and cool and then peel off the skin (you can do this with your fingers or the tip of a paring knife)

- Shred the potatoes with a ricer, add some of the sour cream, if using, and your choice of optional ingredients.

- Taste and adjust the seasoning and get ready to fill your pierogi circles.

- o make the pierogi dough circles:

- Roll the refrigerated dough out on a lightly floured surface as you would a pie crust.

- Cut circles with a large glass or cutter (see note about a pierogi-ravioli-embanada cutter in the story above)—4 inches is a nice generous size but you can make them smaller.

- Top each dough circle with some potato mixture. You will have to experiment with the amount of filling depending on the size of your circles; 1 rounded tablespoon works well with a 4-inch circle.

- Fold half of the dough circle over the other half and pinch the seams together.

- If you are making the pierogies for future meals, you can freeze them on a tray and then store them in freezer bags for 3 to 4 months.

- If making them for now, start a pot of boiling water and add some salt.

- Add your pierogies a few at a time. Don’t crowd them because after they sink to the bottom they need room to float to the top, which is when they are ready to be removed.

- Have ready a frypan heated with a small amount of sizzling butter and some diced fried onions, if desired. Sauté the pierogies in the butter (and onions if using) and remove to a warm platter or individual plates and serve with some of the melted butter and onions, with a dollop of sour cream as well.

- If you lightly fry some diced yellow onions in butter (not margarine) you can add a small portion of them to the filling as an option.

- Save the rest of the onions and add them to the finished dumplings when you sauté them.

Fascinating history. I don’t think we appreciate the scientific discovery of what we eat. And take for granted.