After owning one of the best cooking stores in the US for 47 years—La Cuisine: the Cook’s Resource, in Alexandria, Virginia—Nancy Pollard now writes Kitchen Detail, a blog about food in all its aspects—recipes, film, books, travel, superior sources and food-related issues. She and her husband, the Resident Wine Maniac, have recently moved to Italy.

After owning one of the best cooking stores in the US for 47 years—La Cuisine: the Cook’s Resource, in Alexandria, Virginia—Nancy Pollard now writes Kitchen Detail, a blog about food in all its aspects—recipes, film, books, travel, superior sources and food-related issues. She and her husband, the Resident Wine Maniac, have recently moved to Italy.

I DON’T HAVE a bucket list, but there are things that were available to me when I lived in Alexandria, Virginia, that I wish I had taken the time to view. Many of them are not as obvious as the African American Museum in DC, for which we failed to get tickets on several occasions. In my own neighborhood, we missed the chance to tour Carlyle House when it was the set for a television series based on the Civil War . . . and I walked past it almost every day. And, of course, living across from Gadsby’s Tavern, you would think that I would have looked at the replica of a Founding Fathers–era ballroom, whose original woodwork is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, which ironically we did manage to see. But the local version, half a block from our house, I missed. Apparently, after much begging, the Met sold only the genuine door back to Gadsby’s Tavern Museum.

Philosophical Fruit

Other treasured spots are lesser known, such as the US Department of Agriculture’s museum in Beltsville, Maryland. I found out about one of the remarkable collections of the National Agricultural Library through my son-in-law, who is interested in all things cerebral. He sent me a link to an article and intriguing video from Aeon a weekly digital magazine that, according to its website, “asks the biggest questions and finds the freshest, most original answers, provided by world-leading authorities on science, philosophy and society.” I’ve always been fascinated with agricultural products from a cook’s perspective, but I now appreciate their complex scientific historical context.

Pomologically Speaking

In the 19th century, the growing of fruits and nuts became a multi-million-dollar business. And the term “pomology” is the science of growing fruit. Orchardists and nurserymen (Johnny Appleseed was one, as well as a bit of a religious crackpot) could not patent their innovations, as there was a law against filing a patent on a living organisms, according to Gastro Obscura. Stealing from plant breeders was not uncommon. It was not until 1930 that the Plant Patent Act protected the property rights of fruit innovators. The Department of Agriculture’s catalogue of these meticulous paintings was the first federal effort to create a register of a fruit’s provenance and distinctive characteristics to help protect their creators.

This grand project was started in 1886 and terminated in 1942. Its continuing harvest is not only the pleasure of viewing 7,584 watercolor renderings of fruits and nuts, but also the fostering of appreciation for the history behind varieties (some now extinct) that grew where cameras did not exist. Some orchardists are currently trying to bring back some of these varieties. One is in North Carolina and has revived over a thousand varieties of apples. I would even venture to say that these paintings make each subject more delicious and seductive than a photograph ever could.

Opportunity Knocks

What I found even more intriguing is that this project started just when women were first allowed into art schools in the US, offering one of the few areas of artistic employment for women. Although more than 60 artists contributed to this massive undertaking over 56 years, most of the paintings were accomplished by nine artists, and six of them were women. Wikipedia states that the top three women artists, each contributing more than 1,000 works, were Deborah Griscom Passmore, Amanda Almira Newton, and Mary Daisy Arnold.

Looking through the collection, which has been put in digital format by the National Agricultural

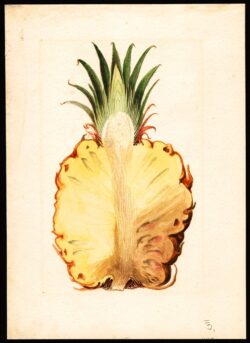

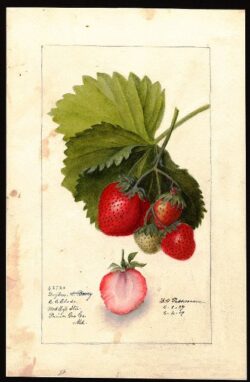

Looking through the collection, which has been put in digital format by the National Agricultural Library, the vibrancy and attention to detail exhibited by the women artists compared with that of some of their male counterparts is striking. Here is the pineapple drawing submitted by J. Marion Shull and one of the strawberry plants submitted by Deborah Griscom Passmore. Little is known about Mary Daisy Arnold, but looking through the collection, her renderings really jump out at you.

Library, the vibrancy and attention to detail exhibited by the women artists compared with that of some of their male counterparts is striking. Here is the pineapple drawing submitted by J. Marion Shull and one of the strawberry plants submitted by Deborah Griscom Passmore. Little is known about Mary Daisy Arnold, but looking through the collection, her renderings really jump out at you.

Some of the women moved up in the ranks at the USDA and held administrative positions at a time when women were not generally employed at an executive level in the private sector.

This chance encounter on my (old) home turf is one I’m grateful not to have missed. What wonderful serendipity: a recommendation for a digital magazine led me to to discover this fascinating collection and its history, plus an opportunity to view the video (with an eye-popping flipbook) of Sebastian Ko, a Canadian filmmaker. The experience was as much a wonder as the Pomological Collection itself.

Lovely and informative writing.