After owning one of the best cooking stores in the US for 47 years—La Cuisine: the Cook’s Resource, in Alexandria, Virginia—Nancy Pollard now writes Kitchen Detail, a blog about food in all its aspects—recipes, film, books, travel, superior sources and food-related issues. She and her husband, the Resident Wine Maniac, have recently moved to Italy.

I RECENTLY wrote to a friend who also had a kitchen store in northern Virginia and is a devoted cook and baker. I confided that the Resident Wine Maniac and I, after a couple of months of dining out and cooking in our Ikea kitchen built for one here in our temporary furnished apartment in Bologna, Italy, that our bodies felt “cleaner.” We felt better, even after indulging in the somewhat heavy cuisine for which Bologna is noted. This was not something we had anticipated, and my friend wrote back a scathing criticism of the lax food regulations in the US. In addition, some other KD readers asked me about the differences in food regulations, grocery shopping, and food labeling between the US and Italy. As a member of the European Union, Italy’s food policies must be in line with EU regulations. In this post, we try to unravel only some of the differences in food regulation and shopping choices.

Who Handles Your Groceries

Who Handles Your Groceries

In the US, the Department of Agriculture, which was founded by Abraham Lincoln in 1862 and now encompasses almost 30 federal agencies, has a broad regulatory scope that includes farming, ranching, and also forestry industries. It is also “tasked with administering several social welfare programs, including free school lunches and food stamps,” according to Investopedia. Independent of the USDA is the Food and Drug Administration, which regulates dairy, seafood, produce, packaged foods, some aspects of our egg supply, and even our bottled water. In a weird separation of regulatory powers, game and “exotic” meats are inspected and regulated by the FDA rather than the USDA.

In theory, the USDA is tasked with keeping our nation’s supply of meat, poultry, eggs, and dairy products in a healthy state; in addition, sustainable agricultural land management comes under its purview. It also has to answer to the community that raises our food. So there exists today in the US an extensive interplay between food producers and the federal agencies that are supposed to regulate them, with the Food and Drug Administration an additional major player. While it would seem logical for the FDA to be part of the USDA, it remains a separate agency, resulting in some bizarre separations of regulatory powers. While the FDA regulates our seafood, an exception is made for catfish, which comes under USDA control. Egg products (out of the shell) are regulated by the USDA, while whole eggs are under the purview of the FDA. The USDA is in control of fresh fruit and vegetable production, but the FDA controls the processed versions. With meat products, it’s even more complicated. It was best explained in www.govloop.com:

state; in addition, sustainable agricultural land management comes under its purview. It also has to answer to the community that raises our food. So there exists today in the US an extensive interplay between food producers and the federal agencies that are supposed to regulate them, with the Food and Drug Administration an additional major player. While it would seem logical for the FDA to be part of the USDA, it remains a separate agency, resulting in some bizarre separations of regulatory powers. While the FDA regulates our seafood, an exception is made for catfish, which comes under USDA control. Egg products (out of the shell) are regulated by the USDA, while whole eggs are under the purview of the FDA. The USDA is in control of fresh fruit and vegetable production, but the FDA controls the processed versions. With meat products, it’s even more complicated. It was best explained in www.govloop.com:

Products with more than 3% raw meat, 2% or more cooked meat (or other portions of the carcass), or 30% or more fat or tallow, are under USDA jurisdiction. Conversely, products with less than 3% raw meat, less than 2% cooked meat (or other portions of the carcass), or less than 30% fat or tallow, are overseen by FDA, as are products containing “other meats.”

My favorite division of regulatory power between the two agencies is the one that governs our sandwiches. The USDA controls open-faced sandwiches, where the ratio of meat to bread etc. is more than 50%. But your standard sandwich with two slices of bread (with a filling that comprises less than 50% of the whole sandwich) is controlled by the FDA. But even with two competing regulatory agencies supposedly overseeing the safety and quality of our food, other players lend a heavy hand that can undermine the finest intentions. An unfortunate combination of regulation “influencers,” otherwise known as industry lobbyists, add their shenanigans to the mischief created by a preponderance of former Big Ag executives getting appointed to influential positions within those agencies. This combination has considerably weakened the regulatory powers of both agencies.

European Union Rules

The EU is an association of some 20-plus nations. All EU nations have to abide by the standards and certifications of the European Food Safety Authority or EFSA. That said, the EFSA is, at least currently, an authority that is not tainted extensively by industry insiders. It produces scientific opinions on food additives, allergens, animal feed, and allowable pesticide levels in food. These opinions are used to create a more preventive or protective approach in the EU regulation of food.

The EU is an association of some 20-plus nations. All EU nations have to abide by the standards and certifications of the European Food Safety Authority or EFSA. That said, the EFSA is, at least currently, an authority that is not tainted extensively by industry insiders. It produces scientific opinions on food additives, allergens, animal feed, and allowable pesticide levels in food. These opinions are used to create a more preventive or protective approach in the EU regulation of food.

(Note that the accompanying images were taken from foodbabe.com before Brexit.)

One commonly used analysis is that food additives are deemed innocent in the US until overwhelmingly proved guilty, while in the EU they have to be proven overwhelmingly unharmful to human consumption to be allowed in food. In fact, US companies selling their products in the EU alter their composition so that the EU version is often better-quality. Failing that, at least the companies cannot use the number of additives and artificial colorants that are allowed in the US.

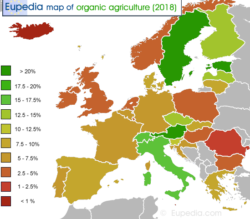

Also, more organic or biological farming is done in EU member countries than in the US. As an example, barely 1% of farming in the US is organic, whereas in Italy it is well over 6%. In the EU community at large, the percentage is a bit over 9% and, interestingly, the organic farms can be larger than conventional farms and run by a younger generation of farm administrators. Another difference is that, while the US recently allowed hydroponic farming to be labeled organic, that is not allowed in the EU. Only plants naturally grown in water, like watercress or rice, are allowed organic certification if they meet the standard. This was a very hotly contested battle lost by organic farming groups in the US, who I think rightly maintain that an organic certification should require a dedication to renewing the soil in a sustainable manner for the next crop, and should not include crops that are simply fed nutrients while in a water bath.

Also, more organic or biological farming is done in EU member countries than in the US. As an example, barely 1% of farming in the US is organic, whereas in Italy it is well over 6%. In the EU community at large, the percentage is a bit over 9% and, interestingly, the organic farms can be larger than conventional farms and run by a younger generation of farm administrators. Another difference is that, while the US recently allowed hydroponic farming to be labeled organic, that is not allowed in the EU. Only plants naturally grown in water, like watercress or rice, are allowed organic certification if they meet the standard. This was a very hotly contested battle lost by organic farming groups in the US, who I think rightly maintain that an organic certification should require a dedication to renewing the soil in a sustainable manner for the next crop, and should not include crops that are simply fed nutrients while in a water bath.

On a personal level, US grocery stores seem to have a huge variety of products, even within a given category. In my current grocery shopping, there is less selection here, except for types of pasta! For instance, we might not have the several different varieties of the same fruit offered at the supermarket, but the one or two offered will vary according to season and usually taste better. Dairy products are often touted from different regions, instead of from large corporate producers. And in most cases, grocery chain house brands exhibit better quality to me than those I purchased in the US. And large “economy” size is a plus in the US, where it is not here. The only thing that comes in a size larger than what is available in the States is paper towels. You purchase a huge roll without floral designs and it sits on your counter. I kind of like that.

category. In my current grocery shopping, there is less selection here, except for types of pasta! For instance, we might not have the several different varieties of the same fruit offered at the supermarket, but the one or two offered will vary according to season and usually taste better. Dairy products are often touted from different regions, instead of from large corporate producers. And in most cases, grocery chain house brands exhibit better quality to me than those I purchased in the US. And large “economy” size is a plus in the US, where it is not here. The only thing that comes in a size larger than what is available in the States is paper towels. You purchase a huge roll without floral designs and it sits on your counter. I kind of like that.

Even Italy’s industrial strawberries are smaller and lack the huge white cores typical of the dread Driscoll ones. And, yes, local stores have what my son-in-law calls pane finto, or fake bread, which we would term a white sandwich loaf. Still, we look for groceries that we liked at home and try local variations. Sometimes with success, other times, not so much. Each of us has individual heartbreaks. While my husband laments the loss of Hellmann’s or Duke’s mayonnaise for his BLT sandwiches, I have yet to find a great corn tortilla like the ones produced by Ula in Virginia.