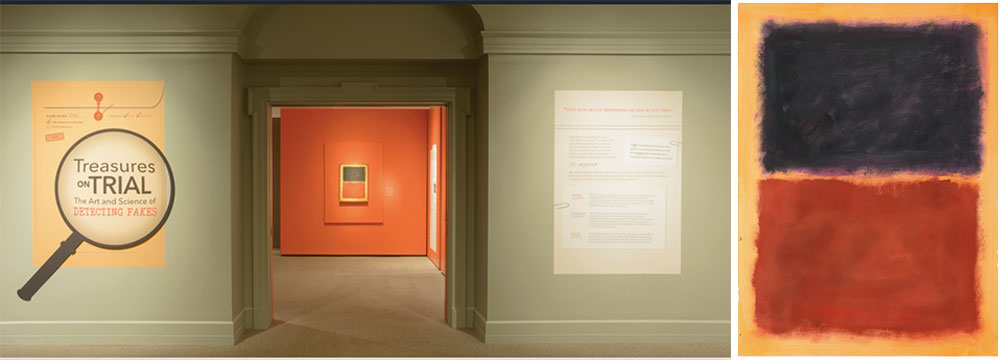

“Treasures on Trial” at Winterthur back in 2017 opened with this dramatic painting (show also at right) by “Mark Rothko” (not really). The painting was part of the 2011 scandal in which the renowned Knoedler Gallery in New York was accused of having sold $60 million worth of works purportedly by important Abstract Expressionists such as Rothko, Robert Motherwell and Jackson Pollock. In fact, they were all painted by an artist in Queens, New York, Pei-Shen Qian. The gallery is now closed, and many settlements were made.

WEBSITES ARE their own kind of time machine: It you miss an art exhibit, even by several years, you may get lucky and find that its treasures, and all the scholarship behind them, have been memorialized by an enterprising museum in a rich and captivating online show.

Such is the case with an engaging exhibit mounted in 2017 at Winterthur, the estate and museum of the renowned antiques collector Henry Francis du Pont in Winterthur, Delaware, near Wilmington. “Treasures on Trial: The Art and Science of Detecting Fakes” cast a wide net, looking at faked paintings, fraudulent provenances and antique furniture cobbled together with an eye toward fooling collectors; it even features a few rogue forgers, a couple of them quite entertaining in their way.

No area of collecting seems to be immune from trickery: sports (a genuine 1890 baseball mitt passed off as one used by baseball great Babe Ruth), decorative arts (a piece of 18th-century porcelain embellished around 1975 to increase its value), fashion (a genuine ostrich-skin handbag fashioned to replicate a $35,000 Hermès Birkin bag).

You can spend an hour or more working your way through the online exhibit, learning the strangely entertaining stories of fraudsters and posers, reading along as some of them meet their just deserts in a court of law or an FBI raid. It’s a shame to have missed the show back in 2017, but with Covid-19 keeping us glued to our laptops it’s nice to have such a worthy diversion.

Here are some examples of exhibits from the show.

—Nancy McKeon

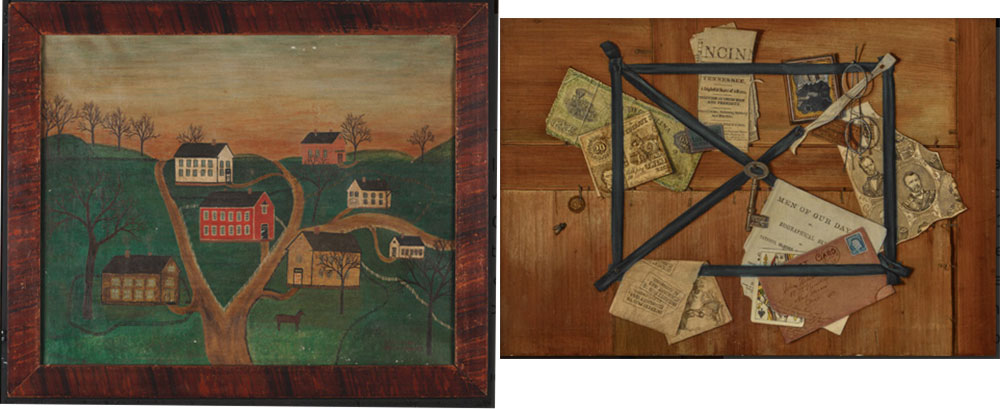

Robert Lawrence Trotter painted in the folk-art style, but after American folk art began commanding record prices, he started creating fake provenances for his pieces. He eventually admitted to having sold 52 paintings to art dealers and having consigned 29 to auction houses around the country. Some collectors elected to keep the forgeries after they were discovered, some for teaching purposes, others simply for the enjoyment of the piece. / Left, “Village Scene” by Robert Lawrence Trotter, 1985, courtesy Art Conservation Department, Buffalo State College. Right, Untitled, in the manner of John Haberle, by Robert Lawrence Trotter, circa 1989. Yale University Art Gallery, donated by the US Department of Justice, FBI.

Leather goods, albeit of very different kinds, have had a role in fraud.

LEFT: A genuine 1890 baseball glove was bought on eBay for $750, then resold for $200,000 after the eBay buyer claimed it had been Babe Ruth’s. The fraudster got caught. / Photo courtesy of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, New York office.

RIGHT: This elegant ostrich “Birkin” bag is not by Hermes. Although well made, one big giveaway is that the “spores” or bumps of the ostrich skin are hammered down by Hermes to create a smooth surface. Not so with this counterfeit. / Courtesy of an anonymous donor.

The Dutch forger Han van Meegeren began by faking “rediscovered” works by the likes of Vermeer, Pieter de Hooch and Frans Hals. Geoffrey Webb, one of the “Monuments Men” who investigated art looted by the Nazis in World War II, donated this copy, right, of “The Procuress” by Dirck van Baburen, assuming it had been painted by van Meegeren. As chemical analysis has become ever more sophisticated, Webb’s judgment has been confirmed. / Left, “The Procuress,” by Dirck van Baburen, 1622. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, M. Theresa B. Hopkins Fund. Right, attributed to Han van Meegeren, after Dirck van Baburen, circa 1940. The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London.

It’s not only works of art that get forged, of course.

LEFT: In fashion, there are knockoffs and licensed copies, and then there are out-and-out counterfeits. The Chanel wool houndstooth suit on the left is from the spring 1971 collection of the House of Chanel. On the right, a reasonable-enough copy, made with a lesser-quality wool with a slightly larger pattern was made in America by a US manufacturer, also in 1971. The lining is acetate, not silk, the buttons different and the buttonholes and grosgrain-ribbon trim machine-stitched. / Both suits from the collection of Claire B. Shaeffer.

RIGHT: George Washington was the first president of the US, of course, but he was also the first president of the Society of the Cincinnati, a fraternal group formed by officers from the American Revolution. As such, he purchased 302 pieces of Chinese export porcelain custom-decorated with the figure of “Fame” holding the Society’s badge. Both plates, top and bottom, are late-18th-century hard-paste porcelain. But it has been determined that the plate on the bottom was probably a plain antique plate purchased in 1975 at a London auction and then refired (there are telltale marks on the reverse) after the Society badge was added, thus greatly increasing its value. / Genuine Washington plate, gift of Henry Francis du Pont, 1963. The copy is from the Reeves Collection, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia.

Like a game of “hot potato,” some forgeries continue to circulate even after being revealed, especially if a buyer has discovered he has purchased a fake and tries to get rid of it. Such was the case of this fake Andrew Wyeth, an attempt at an exact copy of a Wyeth watercolor. / “Wreck on Doughnut Point,”

watercolor in the style of Andrew Wyeth, courtesy of David Hall.

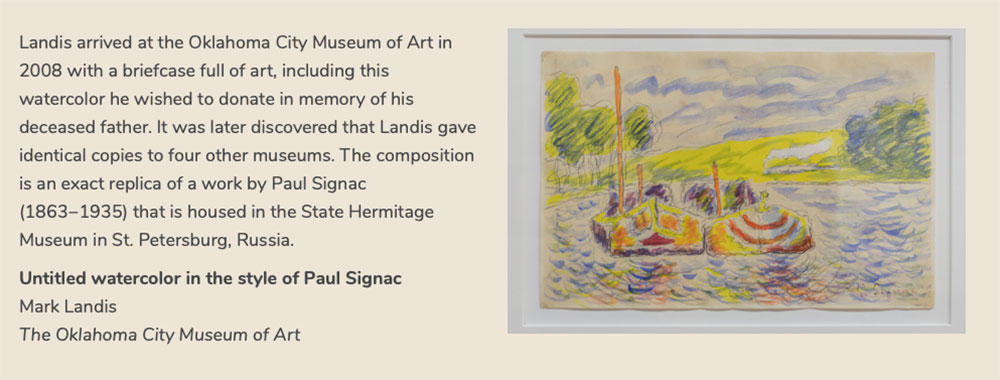

Compelled by mental illness, Mark Landis made replicas of paintings, in this case a watercolor in the style of Paul Signac, a French neo-Impressionist. Landis was caught out but was not charged with fraud because he never sold his works, only offered to donate them to museums. / The Oklahoma City Museum of Art.