LEFT: Carrie Mae Weems’s “After Manet” is a photograph that puts African American figures into a Manet setting. It dates from 2002. / Carrie Mae Weems, “After Manet,” 2002 (printed 2015), Chromogenic print, courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, © Carrie Mae Weems.

RIGHT: Several artists in the Phillips exhibition riff on Manet’s famous, and quite scandalous, “Dejeuner sur l’Herbe.” This 2017 work by Ayana V. Jackson populates the well-known forest glen with strong female characters replacing Manet’s naked white women. It is called “Judgment of Paris” because the Manet painting is itself a riff on an earlier work, a 16th-century engraving in which the mythological Paris has to judge which goddess is most beautiful (hint: he chooses Venus). / Ayana V. Jackson, “Judgment of Paris,” 2018, Archival pigment print on German etching paper, courtesy of the artist and Mariana Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago.

MANY SCHOLARLY words have been written about how much modern art owes to African sculpture, visible in flattened forms and the human face expressed in abstract simplicity. But the “Riffs and Reflections” exhibition at the Phillips Collection in Washington DC looks in the other direction, at modern African American artists who embraced the modern idioms of Impressionism, then abstraction, and tried to become part of the evolving art scene in Europe.

The fact is, though, that the names William H. Johnson and Hale Woodruff don’t ring bells as loudly as Matisse, Manet and Monet. But the Black artists persisted, endeavoring to put African Americans in the picture, literally. albeit often abstractly. And while the European appropriation of African forms went largely unacknowledged, more recent African American artists have addressed the European works directly, riffing on them with verve and bold color and a healthy dose of politics.

The contemporary artist Titus Kaphar created “Pushing Back the Light,” left, in 2012 as a commentary on Monet’s “Woman With a Parasol,” right, from 1875. Black tar surrounding the female figure (actually Mme Monet) literally sends the luminous Impressionist light to the edges of the canvas, the artist’s response to the fact that while Impressionists in Europe were capturing idyllic scenes of daily life, the African continent was being carved up by European nations into colonies with natural and human resources to exploit. / Left, Titus Kaphar, “Pushing Back the Light,” 2012, Oil and tar on canvas, courtesy of the artist and the photographer, Christopher Gardner. Right, Claude Monet, “Woman with a Parasol–Madame Monet and Her Son,” 1875, Oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon.

The Phillips exhibit, originally intended to end May 24, will be extended through January 3, 2021. Perhaps by then we will be able to see the show in person, but for the moment the Phillips remains closed and the offerings on its website will have to suffice.

And they do! The sheer delight of discovering these works outweighs the social distancing of the moment.

—Nancy McKeon

Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition, phillipscollection.org. The Riffs and Relations catalogue, written by the exhibit’s curator, Adrienne L. Childs, is $50 ($45 for members) and can be ordered through museumshop@phillipscollection.org or through Amazon.

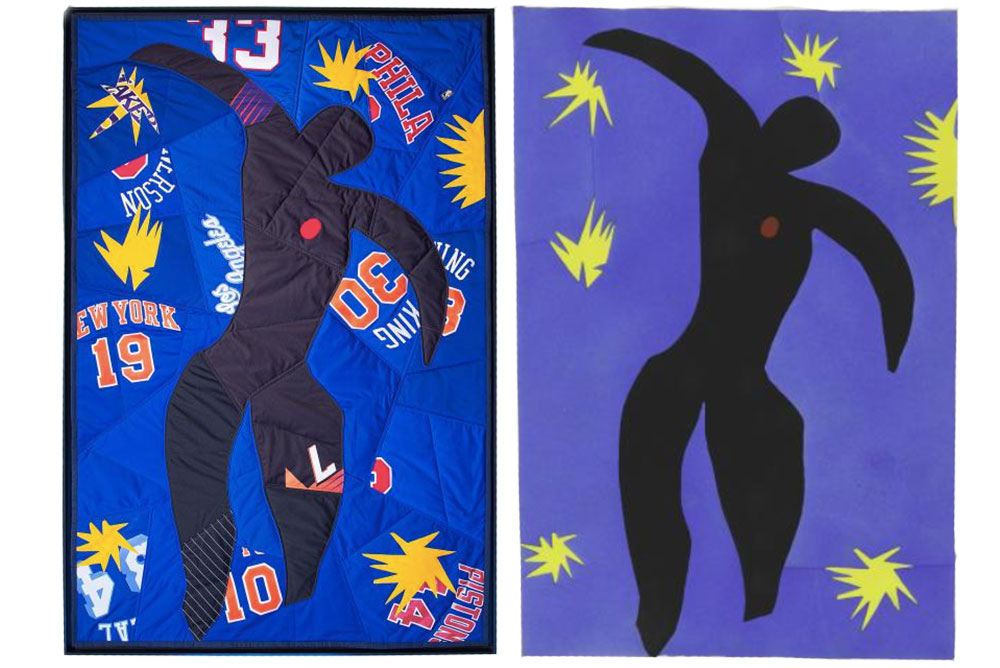

Another riff is by Hank Willis Thomas’s 2016 “Icarus,” left, which directly quotes from Matisse’s “Icarus,” right. But Thomas created this quilt using sports-team logos and jerseys (also, the Thomas quilt is meant to be horizontal). / Left, Hank Willis Thomas, “Icarus,” 2016, Quilt, Collection of Debbie and Mitchell Rechler, © Hank Willis Thomas, Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery. Right, Henri Matisse, “Icarus,” plate VIII from the illustrated book “Jazz 1947,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lila Acheson Wallace, 1983.

“The Card Players” by Hale Woodruff, from 1930, has all the dramatic distortion of planes and faces that European artists were experimenting with. / Hale Woodruff, “The Card Players,” 1930, Oil on canvas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, George A. Hearn Fund, 2015.

Exposure to Cezanne, Van Gogh and Soutine during his Paris years led South Carolina-born William H. Johnson to move beyond his academic training and experiment with movement in form. His later work, after he returned to the United States, shifted once again–simpler, flattened characters more in the spirit of Jacob Lawrence. / William H. Johnson, “Cagnes-sur-Mer,” 1928–29, Oil on canvas mounted on board, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The John Axelrod Collection—Frank B. Bemis Fund, Charles H. Bayley Fund, and The Heritage Fund for a Diverse Collection.

—

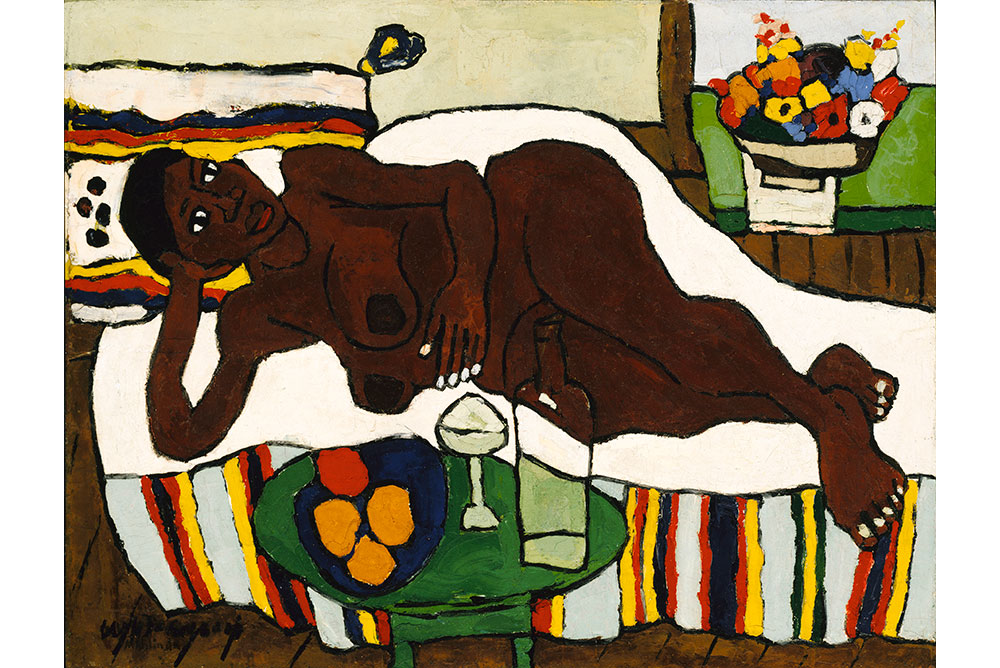

Bold form and color marked later work by William H. Johnson. / William H. Johnson, “Nude,” 1939, Oil on burlap, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC, Gift of the Harmon Foundation.

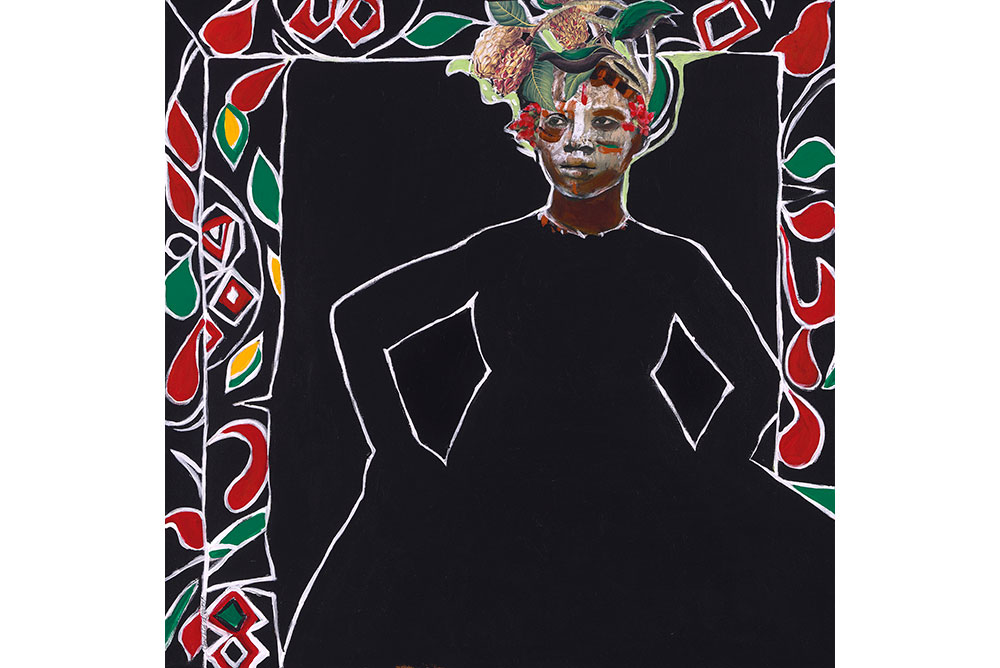

Mixed media meld painting and traditional craft in “And She Was Born,” by Janet Taylor Pickett. / Janet Taylor Pickett, “And She Was Born,” 2017, Acrylic on canvas with collage, courtesy of the artist.