By Janet Kelly

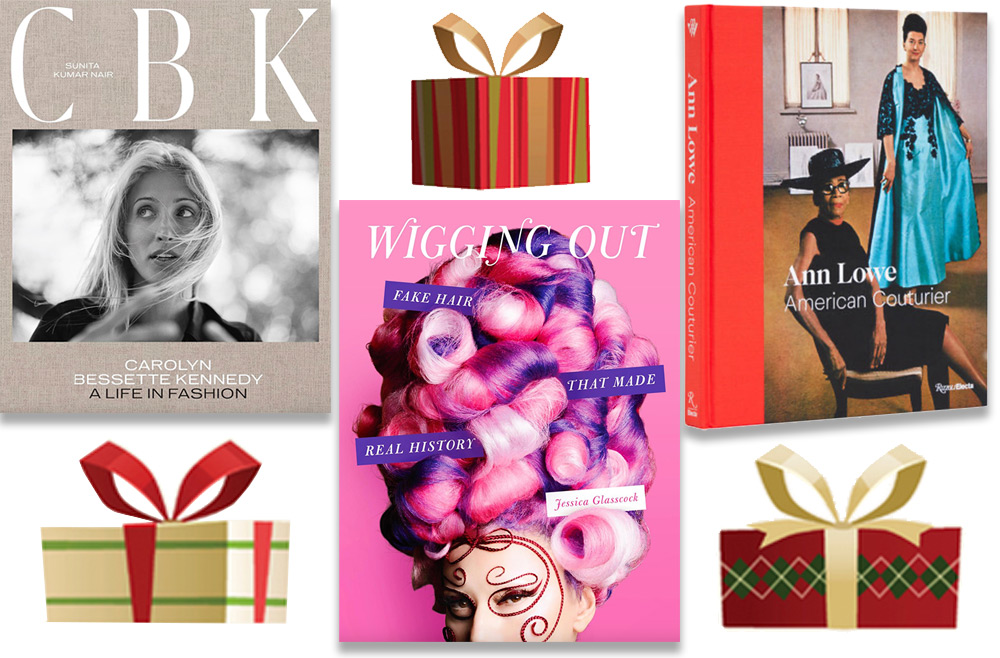

BEFORE JFK, Jr. was even on her radar, in the late 1980s Carolyn Bessette Kennedy’s own star was ascending. After a teaching stint, she worked as a saleswoman for Calvin Klein and climbed the ranks to become publicity director for the label’s Manhattan store. She also was a personal shopper for Klein’s high-profile clients and a style muse for Klein. Sadly, her life was cut short in 1999 when she and Kennedy (whom she married in 1996) and Bessette’s sister died in a 1999 plane crash. Now, more than 20 years later, one of the most photographed women in the world, who never gave interviews and never wore logos, is remembered in a new book, CBK: Carolyn Bessette Kennedy: A Life in Fashion ($58.50, Amazon), by Sunita Kamar Nair. It’s filled with pictures of Bessette Kennedy’s most famous looks, along with essays from and interviews with designers, including Gabriela Hearst and Yohji Yamamoto, Michael Kors, Calvin Klein and Tory Burch, about her innate sense of style.

Maybe it’s the influence of HBO’s “Succession” and the idea of “stealth wealth” clothing, but Bessette Kennedy’s understated looks have woven their way into the fashion zeitgeist. C.B.K.’s wardrobe essentials—white shirts, long pencil skirts, jeans, slip dresses and men’s overcoats dominated the 2024 spring runways.

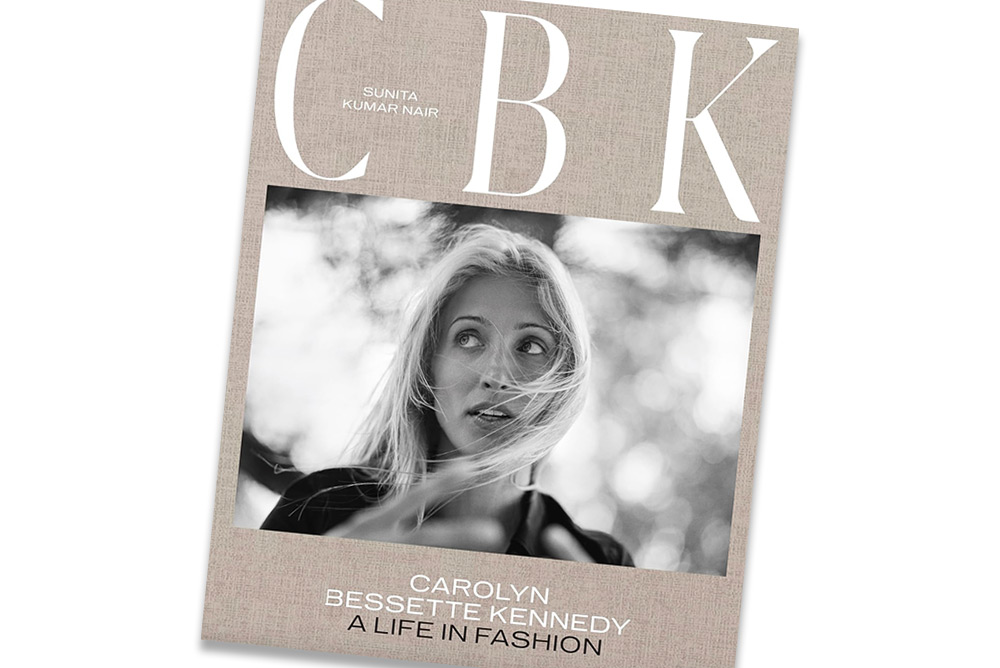

Unlike Bessette Kennedy, Ann Lowe, a Black woman, who grew up in Clayton, Alabama, was rarely photographed and her major contributions to American style were unrecognized during her lifetime (c. 1898–1981). Lowe’s opulent evening gowns and bridal wear were sold in upscale department stores across the country. She even made Jackie Kennedy’s wedding gown and bridesmaid dresses, but when she arrived to deliver them, a butler at the Auchincloss estate told her to enter through the service entrance. (She refused.) Although Lowe’s designs regularly appeared in Vogue and Vanity Fair, her name was a well-kept secret except to rich families like the Rockefellers, the Roosevelts and the Whitneys.

New photography of her couture gowns—including details of her intricate floral embellishments—is giving her long overdue credit in Ann Lowe: American Couturier by Elizabeth Way, published this September by Rizzoli Electa. Essays discuss the hardships and achievements of Lowe’s life, profile Black designers whom she influenced and describe the heroic efforts to preserve her gowns. The book accompanies an exhibit of the same title at Winterthur in Delaware—the largest to date, featuring 40 gowns (many that have never been on public display), showing her evolution as a designer from the 1920s to the 1960s. If you can’t make it to the Brandywine Valley, you can still admire Lowe’s work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute fall 2023 exhibition (through March 3), “Women Dressing Women,” which celebrates the art and creativity of more than 70 womenswear designers, from 1910 to today.

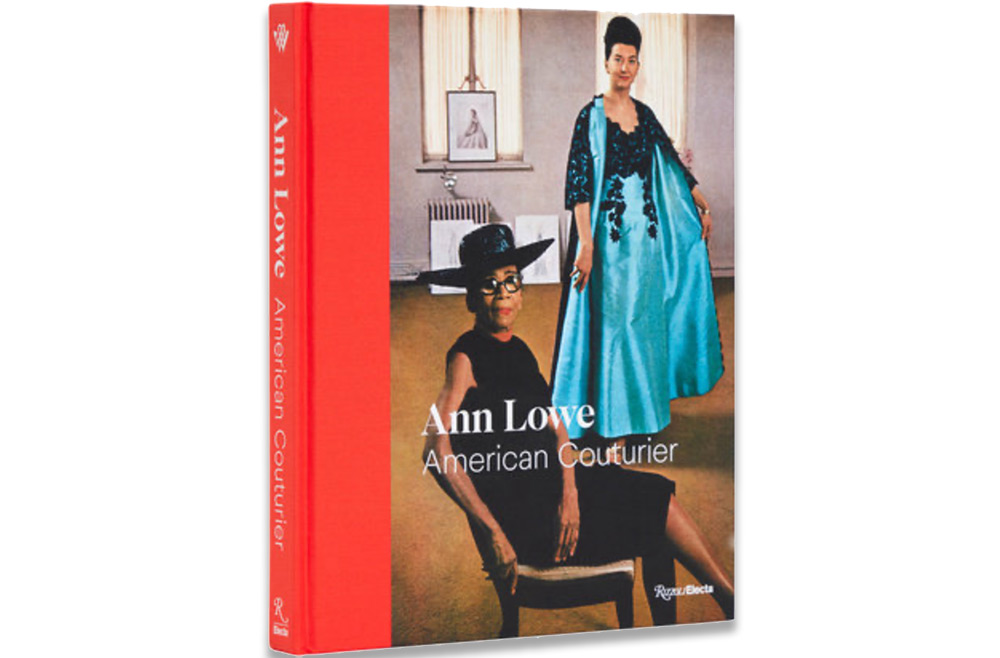

Fashion historian and author of Making a Spectacle: A Fashionable History of Glasses, Jessica Glasscock dives into the history of wigs and hairpieces in Wigging Out: Fake Hair That Made Real History ($22.52, Amazon). Wigs have been around for thousands of years, covering the heads of everyone from Cleopatra and Louis XIV to Diana Ross, Naomi Campbell and 21st-century drag queens. In ancient Egypt, they mainly served ceremonial purposes; for Roman women, human-hair wigs were the gold standard as they were for kings and queens of Europe in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. One of the many reasons Marie Antoinette lost her head was over the extravagant cost of the wigs she had designed for herself—some including actual birdcages. Similarly complicated ones worn on the second season of Queen Charlotte: Bridgerton required the actress playing the queen to wear a neck brace to hold them up. Fast forward to the 1960s when fashion magazines were touting wig wardrobes, and Saks Fifth Avenue was selling $5.99 acetate wigs in colors such as mint, apricot, honey and cobalt blue.

As Glasscock sums up the story of wigs: “Sometimes they were about looking good. Somethimes they were about looking rich. Sometimes they were about looking like one still had hair …” But “where there’s a will, there’s a wig.”

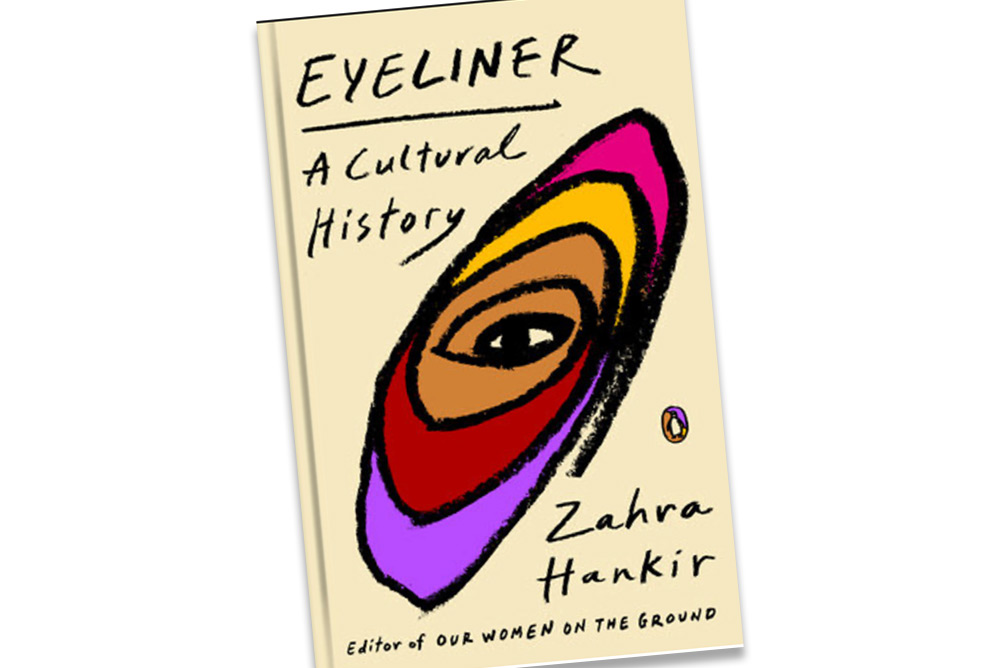

If eyes are the window to the soul, then enhancing their beauty must be a good idea. In Eyeliner: A Cultural History (Amazon, $23.40), Lebanese-British journalist Zahra Hankir makes her case for the cosmetic, which has fascinated her since she was a teenager, transforming her vision of herself. Further inspired by seeing a bust of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti with her kohl-lined eyes in a Berlin museum, she set out to research the history of how humans have been drawn to lining their eyes.

She visits in Chad to interview a group of men who draw kohl on their eyes to attract females. In Iran, she discovers that wearing kohl is an act of resistance; in Mexico, a class marker. A Buddhist monk and makeup artist in Japan tells her eyeliner “accentuates what’s already there.” Traveling to the far corners of the globe, Hankir reports on how eyeliner can signal religious devotion, attract potential partners, ward off evil forces, shield eyes from the sun and communicate without saying a word.

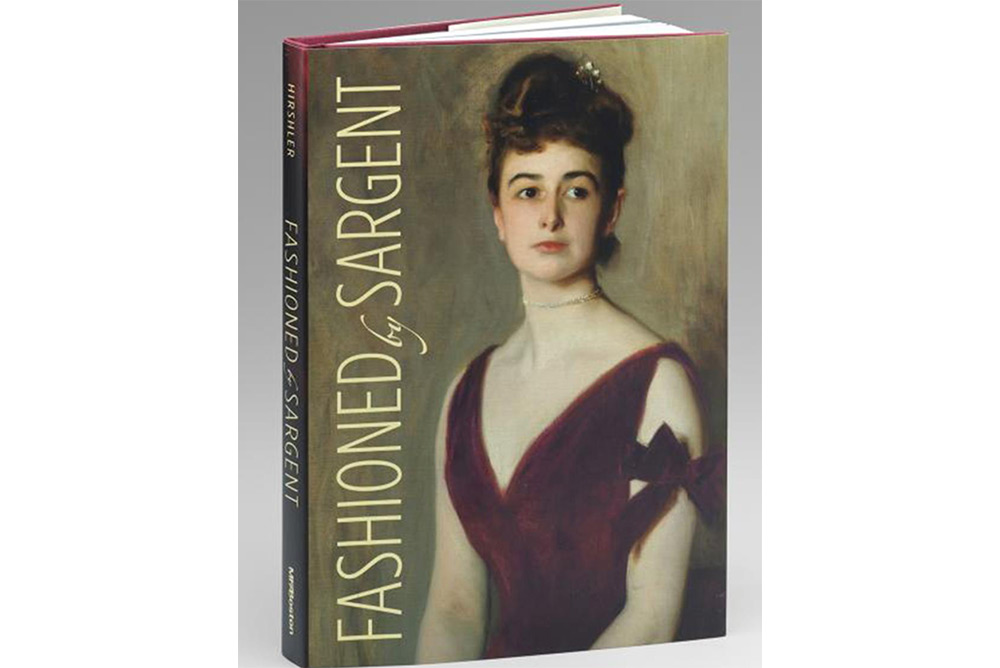

The exhibition, “Fashioned by Sargent,” will be at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston until January 15, 2024. The next best thing to seeing it is getting a copy of the catalogue ($49.98, Amazon) of the same name accompanying the show. Gorgeous images of Sargent’s work are shown alongside equally exquisite costumes of the Gilded Age (including those worn by his sitters). Sargent was a master of showing texture, drape and the way fabrics responded to light. The pictures of sumptuous gowns, gentlemanly dressing gowns and riding clothes may tell you everything you want to know, but if not, essays by art scholars offer new insights into the works of this famous American artist.

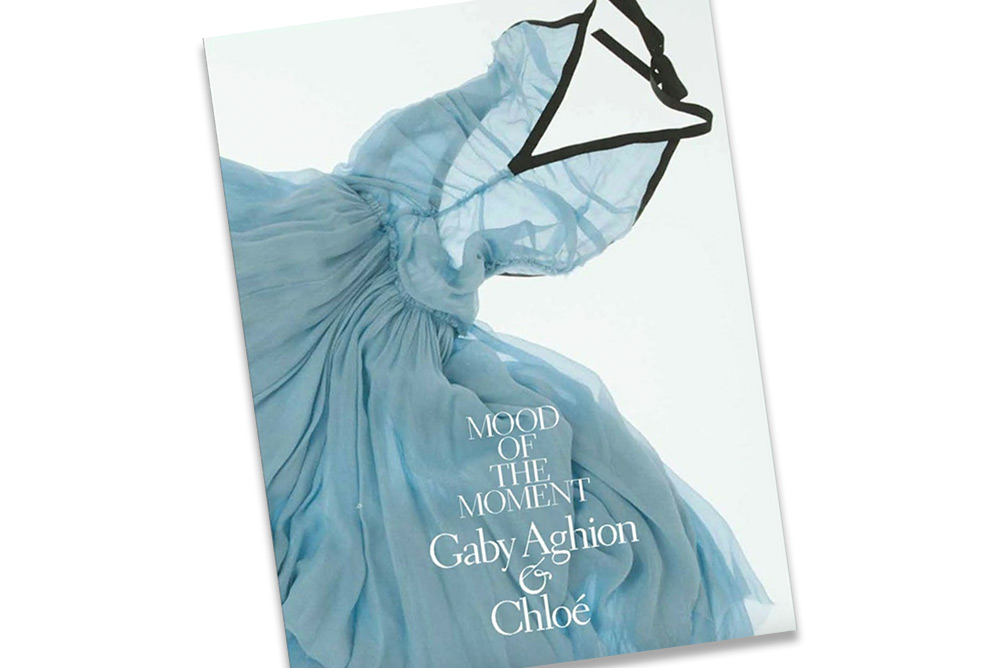

Published in association with the Jewish Museum in New York and concurrent exhibit through Feb. 18, 2024, Mood of the Moment: Gaby Aghion and Chloé ($55.42, Amazon) offers an historical overview of fashion designer Gaby Aghion’s life, career and legacy at French fashion house Chloé. Aghion, an Egyptian emigré, who launched her line in 1952 in Paris, named her design house after a friend named Chloé (there was never a designer of that name).

Illustrated with photos of 70 years of clothing, along with sketches and advertisements, the book tells how Aghion brought a fresh, outsider perspective to French fashion, embracing a transition from haute couture to prêt-à-porter. Essays shed light on the company’s approach to fashion and how it promoted young talent. The first in a line of creative directors after Aghion who embodied and reinterpreted her original inspiration was Karl Lagerfeld, who headed design for 25 years. He was followed by Martine Sitbon, Stella McCartney, Phoebe Philo and most recently, Gabriela Hearst, who in a Washington Post Live discussion, praised Chloé for how much she had learned in her stint there and for being ahead of its time for sustainability in fashion. Hearst is back designing her own label while leading the charge for eco-friendly practices and focusing on the idea that less is more.

MyLittleBird often includes links to products we write about. Our editorial choices are made independently; nonetheless, a purchase made through such a link can sometimes result in MyLittleBird receiving a commission on the sale. We are also an Amazon Associate.

We’ll get to see two of these exhibits in person this weekend in NYC. I’d love to see the Boston exhibit, but not going up until June, so will miss it. Design as culture has always been fascinating.

Janet!

I see inspiration for a potential book club! You make it sound like so much fun to learn more about the anthropology of fashion.