By Nancy McKeon

MENTION CHINA and these days we think Covid-19, or factory to the world, or, most recently, declining population. But in the festive spirit of the Lunar New Year (on Sunday, January 22), let’s remember some of the other things that China and Chinese civilization have meant.

Chippendale style. I think of Chinese Chippendale as a streamlined version of the traditional, sometimes ornate Chippendale style, often rendered in rattan, or made to look like rattan, often a chair or mirror that can read modern or traditional. Well, it turns out I’m wrong (again). Eighteenth-century English chairs had heavy, solid backs, so the airy, sometimes carved splats of Chinese chairs had a lighter look (and no doubt feel). English cabinetmaker Thomas Chippendale was, it seems, channeling the lighter-feeling Chinese style in chairs when he fashioned his designs. So, to overstate a bit, all of Chippendale’s styles were Chinese Chippendale.

What most of us currently refer to as Chinese Chippendale is the further streamlined style we see in casual chairs, even outdoor styles. And they remain graceful solutions in both modern and traditional settings.

On the left, a modern hand-carved Chippendale-style side chair by Design Toscano is, unlike Thomas Chippendale’s, made of pine. It’s on sale for $666.90 at Overstock.com. And guess what? It was made in China. On the right is what is often called the Chinese Chippendale style. The Kara chair is made of rattan in Indonesia. A pair of them in pale gray is $426.59 at Overstock.

A vintage mirror, dating from the 1970s, in the Chinese Chippendale style, complete with pagoda top, is $2,500 from Chairish.com. It’s 30 inches wide and almost five feet tall.

A vintage mirror, dating from the 1970s, in the Chinese Chippendale style, complete with pagoda top, is $2,500 from Chairish.com. It’s 30 inches wide and almost five feet tall.

Folding screens. They can read blowsy as well as stately. Think of a 1940s film noir where the temptress slings her silk hose over the folding screen in her bed-sitter while the flummoxed hero tries not to look. Then imagine a grande dame’s Fifth Avenue drawing room with its Coromandel screen arrayed behind the sofa.

Writer Michael Diaz-Griffith called folding screens “mobile architecture” in a Veranda magazine story. (He also called them “the Band-Aid of the decorative arts,” but that seems a bit mean, if true). They can define a room (and, yes, hide an unfortunate corner pipe or two), and then redefine it with not too much effort.

Had the innovators of the Han Dynasty, 2,000 years ago, had only concealment or protection from drafts in mind, they could have settled on simpler stuff. But artisans fashioned the screens out of wood panels that were then lacquered and embellished (think mother-of-pearl and ivory) to a fare-thee-well. The idea of the screen took off across Asia and eventually Europe. Since then screens have been copied, simplified, amplified, modernized. They can be as light in color and weight as a Japanese shoji screen, as fanciful as a Fornasetti trompe-l’oeil confection; they can be slapped up flat against a wall, or accordioned across it, adding movement to a flat surface.

Made in China, the mid-20th-century double-sided Coromandel screen above is almost 98 inches wide and seven feet tall. The feet stand on copper caps. The screen is on sale for $1,495 from Bryer House Antiques & Interiors of Jacksonville, Florida, through Chairish.com.

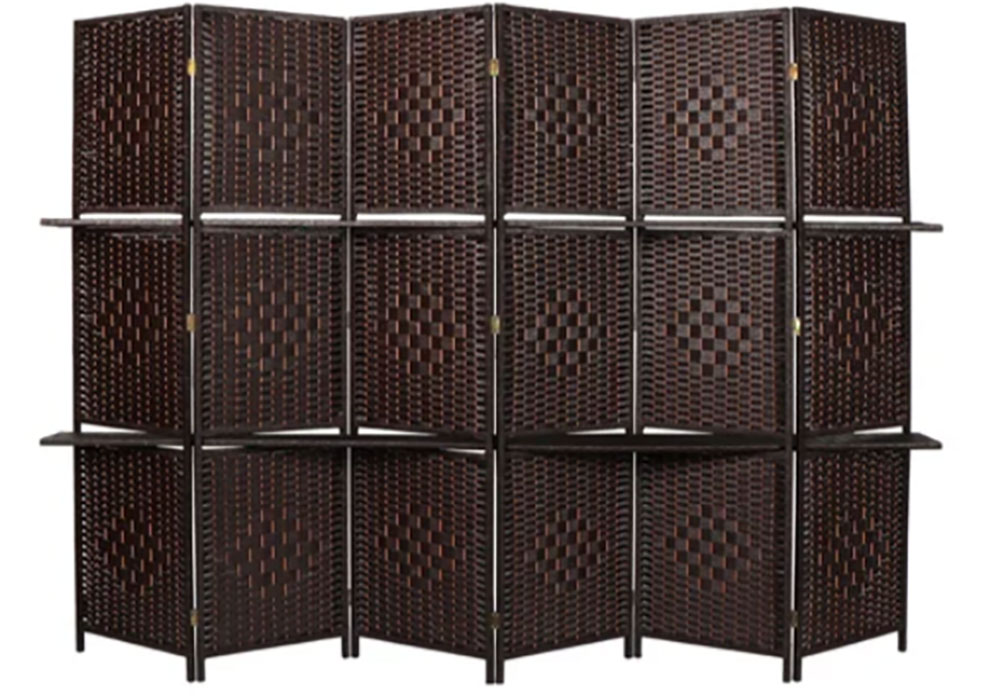

The Rahem Folding Room Divider from Latitude Run adds two clever shelves that can run through the 106-inch-wide bamboo-and-rattan screen to turn it into a display area as well as divider. It’s $156.99 at Wayfair.com.

Rare indeed is this trompe-l’oeil double-sided screen by the late Piero Fornasetti. Made in the 1950s, the screen features Fornasetti’s whimsical Città di Carte, the typical “house of cards” turned into a whole hillside village, a theme Fornasetti played with many times. The rear of the screen is decorated with Fornasetti’s Farfalle (butterflies) design. The seller, on 1st Dibs, is asking $34,500, but you can make an offer.

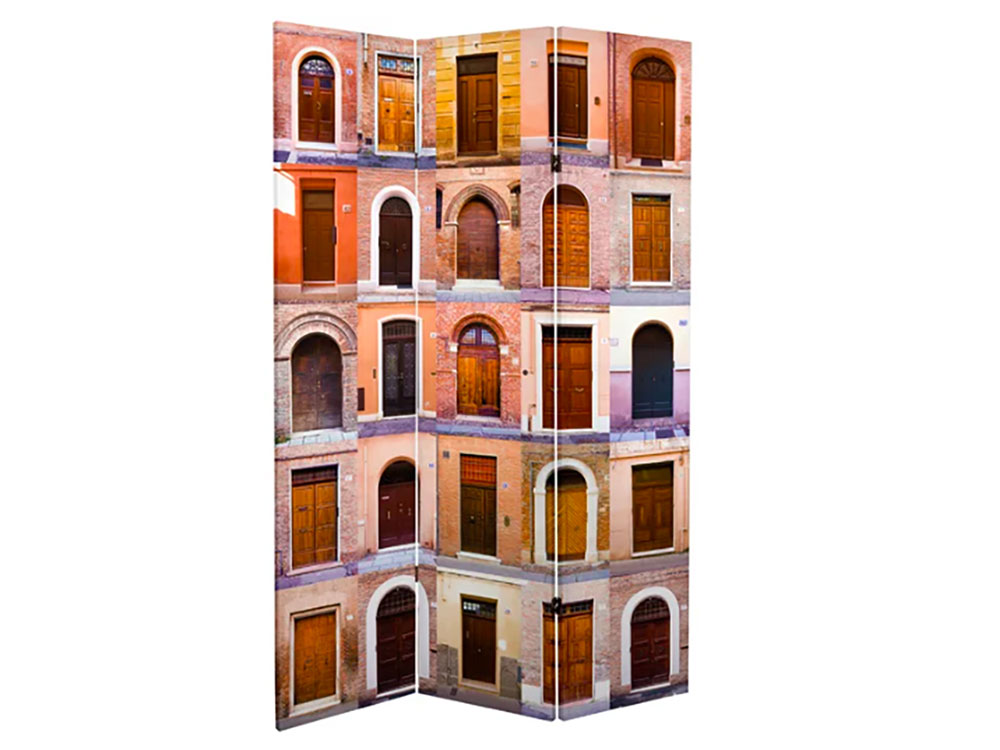

The Rudd three-panel room divider from East Urban Home is made of a wood frame covered on both sides with canvas, one side showing old-world doorways, the other side mimicking one large mediaeval wood door with a heavy lock. Four feet wide and six feet tall, it’s $246.69 at Wayfair.com.

Chinoiserie. The fanciful gardens with birds and butterflies flitting about started out on Chinese screens and wall hangings, but the motifs migrated over the years to modern wallpaper and such everyday items as bedsheets and storage totes.

Chinoiserie has been creating fanciful interiors for hundreds of years. Specializing in hand-painted panels and murals, Gracie Studio in New York offers dozens of patterns as well as custom work. Framed panels of certain styles about 3 feet by 5 feet range in price from about $1,304 to $2,014. Entire rooms depend on pattern and dimensions. Photographer James Merrill shot this dining room for Toni Gallagher Interiors, as shown on the Gracie site. The wall is covered in Silver Peony paper. Technology has enable companies such as Tempaper to offer similar styles in peel-and-stick wallpaper, installed by the company’s technicians.

Almond blossoms on your duvet cover? Why not. The three-piece Eikei bedding set, shown in mustard, also comes in plum and Prussian blue. The set, duvet cover and two shams, is $64.80, $108.80 or $118.80, depending on bed size.

Chinoiserie fabric covers these Susiyo folding storage bins, 11 by 15 inches by 9½ inches tall. The two-pack is $32.99.

Pasta. Italy has no problem acknowledging China as the inventor of paper. At the Museum of Paper and Watermarks in Fabriano in central Italy, the guides make it quite clear that Italian handmade paper took its cue from the Chinese techniques.

Pasta is a different story. It’s clear from his diaries that Marco Polo encountered Asian noodle dishes during his 17-year-long sojourn in China. It used to be argued that he in fact introduced pasta to Italy because of his travels. Those who dispute this theory point to Polo’s mentions of the dishes he eats there; he seems to be saying that he recognizes them as being similar to flat, lasagne-like noodles from home.

It’s also true that Arab travelers were instrumental in taking their pasta-like noodles into areas as far west as Sicily, even bringing their techniques for drying.

Just as flatbreads (pizza? pita?) seem universal and spring from similar needs and similar ingredients, it’s probably the case that Italy’s noodles developed independent of China’s. I bow to scholars who have dived deep into this area. It remains incontrovertible that Italian durum wheat is the harder stuff and allows for all 350 (or more) pasta shapes that have sprung from the Italian imagination. Whereas Chinese noodles are, for the most part, noodles.

Two basic noodle dishes, Italian on the left, Chinese on the right. A coincidence? Well, probably.

Porcelain. It took European potters a long, long time to figure out how the Chinese were able to produce clean, almost translucent “china,” a medium that was strong and with a sparkle that welcomed color and intricate designs. Into the 18th century, English, French, and German potters could pick up on the festive look of the Chinese exports, but the brilliance and rafinesse of the body eluded them.

The secret was the kaolin in the ground, and when the correct mixture was cobbled together in Meissen in Germany, Continental potteries had begun to crack the code. In France, discovery of an ample seam of kaolin led the town of Limoges to begin its now-legendary production of hard-paste porcelain; indeed, to many the word “Limoges” denotes not the place but the porcelain itself. Not correct, but understandable.

Chinese porcelain production continues, and so does the manufacture of low-grade pottery found in kitchen and gift shops. China gave us real porcelain, but it also gave us the decorative look of porcelain, to be had at many levels of quality and many price points.

In the hands of Royal Copenhagen, porcelain manages to look traditional and contemporary at the same time. This 2-quart Blue Fluted Plain tureen is $1,205, to order at Mode Operandi.

From Germany’s Furstenberg Porcelain comes “Fluen,” painted to give the illusion of shifting colors. The gold trim is 24-karat. The bowl above, for cereal or side dishes, is about 6 inches across and $110 at Moda Operandi.

From Germany’s Furstenberg Porcelain comes “Fluen,” painted to give the illusion of shifting colors. The gold trim is 24-karat. The bowl above, for cereal or side dishes, is about 6 inches across and $110 at Moda Operandi.

Classic: This 9-inch-tall 19th-century Chinese blue-and-white porcelain Double Happiness jar with original lid is $650 at Chairish.

Yes, yes, leaving a whole lot out: gunpowder, fireworks, the compass, beheading (oh well). But it would be unfair to our fellow travelers on this planet if we didn’t extend a hearty thank-you, once again, for porcelain. Even now, almost all toilets are made from porcelain. That contribution alone keeps most of us from having to greet each morning atop a galvanized tin bucket. Certainly, the ancient Romans civilized human elimination by engineering it indoors. But the antibacterial properties of porcelain make the substance into the embodiment of the word sanitaryware. And here we sit.

This elongated toilet from American Standard is chair-height, has a “robust flushing system,” and is made of . . . porcelain! It and similar models range from $199 to about $295 at HomeDepot.com.

Excellent! Useful! So glad to be reminded why I’m not mad at the Chinese although I’m now in day 9 of their fabulous flu.

Oh, Jane, sorry to hear that! Feel better fast!

OMGOLLY. What a good history lesson! I didn’t know I liked Chinoiserie, until you showed me.

Ha! A victory over blank walls!