MM: My parents believed in education, structure and discipline. My mother was a convert to the church. My father worked for Franklin Day Planner, a system that manages time down to the minute. There was a predictable rhythm to life. You don’t drink coffee, you don’t drink, you go to church. You were also required to give speeches in church that had to be memorized. The discipline and the memorizing were wonderful training for music, but at the same time it made me feel tremendously boxed in and limited about what I could express.

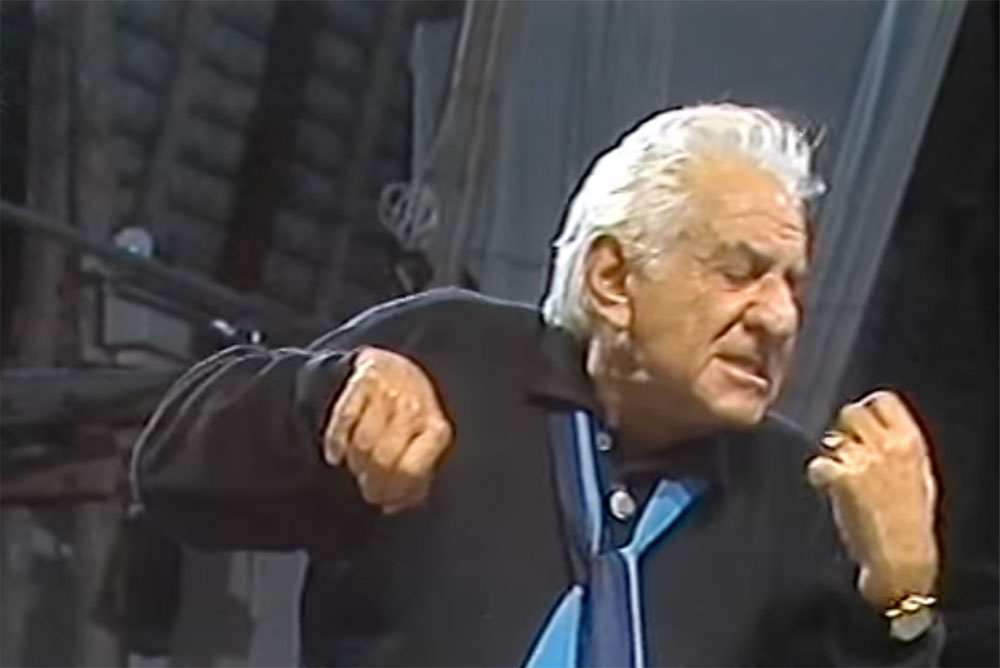

MLB: You refer to Leonard Bernstein as your mentor. How did you meet him? How did he change your life?

MM: At age 19, I was invited to perform at the Schleswig-Holstein Summer Music Festival and tour with Bernstein, who was the guest conductor. I worked with him for several weeks preparing. What struck me most: People never spoke from the stage to the audience—it was not part of the tradition of classical music. But Bernstein did; he spoke to audiences to give them a window into music. He always traveled with a thick book of Shakespeare. When we were performing Midsummer’s Night’s Dream, he read to us about the Queen Fairy, giving us an image of who Queen Mab was and why her sounds would be spidery and light. He didn’t have to teach us how to play violin. He went directly to our minds to inspire us. “That’s what I want to do,” I told myself.

MLB:How did your career change as a result of your time with Bernstein?

MM: After receiving my Master’s, I was playing as a substitute in the Indianapolis Symphony and directing the Indianapolis String Academy. That’s when I saw the disconnect between the rigorous training of young string players and the decline in classical music audiences. This made me broaden my view on what it means to be a classical musician, and I set out to create a performance career around audience engagement. In other words, I wanted to inspire people to love music and support musicians (rather than training more young musicians with uncertain futures.) Bernstein did this, and I believed I could do my own unique version. I developed a three-part model (teacher training, school workshops and interactive concerts) that turned out to be very successful in Germany where I began creating classical music shows with major orchestras. In the style of Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts, I engaged audiences with theme-oriented concerts. When I noticed German kids loved soccer, I put on a show around music and soccer. I brought a retired baker on the stage to make a seven-layer cake to illustrate the structure of music. (I love cakes, and the Germans make the best ones.) Mormonism came in handy here—you were supposed to convert people. I was a missionary for music.

MLB: Sounds like you had as good a time as the teenagers. When did you leave Germany and move to Pittsburgh?

MM: I got married to the concert master of the Pittsburgh Symphony in 2003 and then had two children. I was continuing my work in audience development when CMU hired me to build an entrepreneurship program for musicians that would teach business skills and marketing, as well as how to to deal with performance anxiety, write thank you notes, answer the phone, manage time and schmooze. You don’t have to be the best oboe player, but you have to get along with people. I train students to talk to audiences, not with a bunch of jargon like what key the music is in or when the composer was born or died. But, for example, what was the context of that piece—did Mozart write this because his mother just died? It’s possible to say something with just notes on a page, but that’s only 30 percent of it. As Mozart said, music is between the notes.

MLB: Another big influence on your life and career was Yo-Yo Ma. How did you meet him and what impact did he have on you?

MM: Through my relationship with Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra conductor, Manfred Honeck, I had two post-concert dinners with YoYo Ma in recent years. He was the most humble musician I’ve ever met, and I was struck by his deep awareness of the human condition, his empathy for others and belief that music can have a profound impact on humanity if it is about creating connection rather than the glorification of the artist on the stage. In the past I might have thought of audience engagement as a means of bringing people into the concert hall; he thought of it as a means unto itself: using music to connect with people with whom we may have little in common, to listen and learn and to shine a light on our joint humanity.

MLB: When you turned 50, your life met a big curve ball. How did you face that challenge?

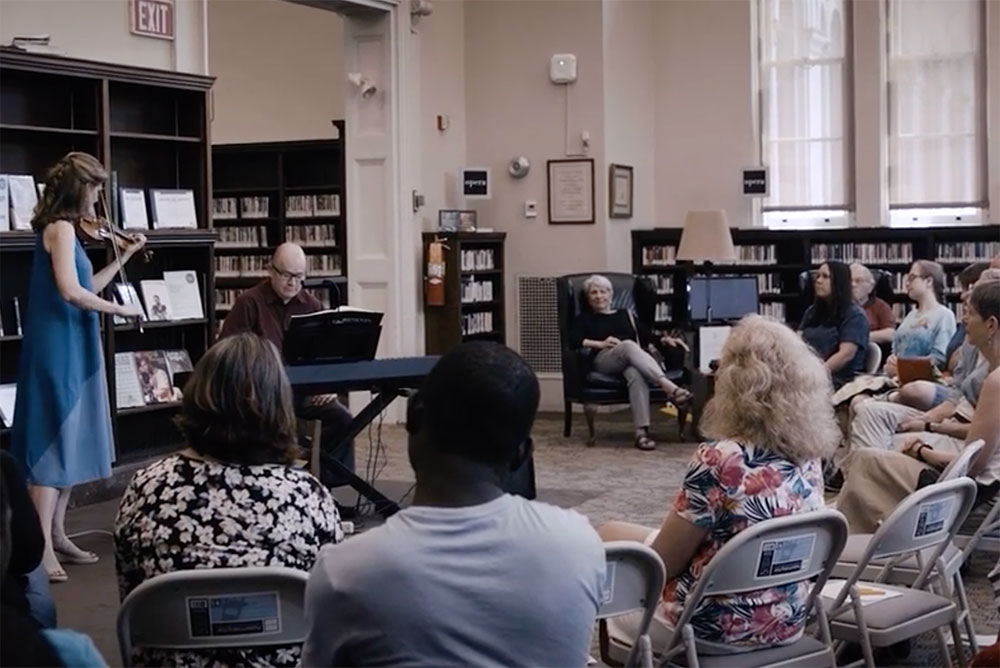

MM: The year I turned 50, I got knocked off my own stage. I was getting divorced and helping my kids through the trauma of the breakup. At the same time, I was asked to perform one of music’s most difficult and sacred pieces, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, at the Edgewood Symphony. I had never done it before, but what inspired me to take it on was that Beethoven was deaf when he wrote it, and besides being deaf, was also anxious and depressed. If he could overcome such adversity to write such beauty, I could learn to play it. It was my own therapy. In February, 2020, I announced that I would perform the concerto 50 times in 250 days for people struggling. I called the project “Beethoven in the Face of Adversity.” At the time, Pittsburgh was reeling from the Tree of Life synagogue shooting, and I got a number of performance requests from families. I also played for someone with ALS, a chronic pain group and many more. I didn’t solicit, it was all by request, and I got referrals through my music network. For my 50th concert, I threw a party for Beethoven’s 250th birthday in Carnegie Hall. In the lobby, I featured photos of people I played for to pass on their stories about what gives you the strength to get up every morning.

MLB: Since then, how would you describe the trajectory of your career?

MM: The irony was just after Beethoven’s birthday, everything went silent and deaf. That summer, I launched “Porch Concerts.” I gave classical music performances on my front porch, along with my kids, who play the piano and harp, and guest musicians who had very few, if any other, gigs. I invited mostly neighborhood folks who would sit outside on the lawn—masked up—and listen. [The successful series just ended this summer.] Starting with “Beethoven in the Face of Adversity” and continuing with Porch Concerts, Azure Family Concerts (music for families with autism) and now the Lullaby Project, my career has gone from being a music missionary to taking the path of Citizen Artist, inspired by Yo-Yo Ma. Instead of bringing people into the hall, I’m going out to the community.

Introduced to Monique at a luncheon several years ago, my initial impression of her was alliterative – gentle, graceful, gracious and gorgeous! Since then, I’ve enjoyed her healing sound baths as well as been entertained by her mischievous sense of humor. Monique is not one to sing her own praises. I could not be more pleased, Janet, that My Little Bird sang instead! Monique, you rock! Xoxoxo

So inspiring.

Exactly my thinking.