Tower 2 of the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC is dedicated to Alexander Calder’s mobiles and stabiles, even a couple of works on canvas and his “drawing in air” (iwire works). Playful but serious, as usual, the works reflect the sculptor’s imagination as well as his technical competence and training. The Gallery commissioned Calder to create a monumental mobile to hang in the central court of I.M. Pei’s new East Building. It was completed and installed after the artist’s death in 1976. / National Gallery of Art, nga.org.

By Nancy McKeon

WHEN YOU STOP to consider what most of us know of the sculptor Alexander Calder—his colorful mobiles bobbing balletically in the air, the monumental stabiles that anchor so many public spaces worldwide, the playful shapes and images—it shouldn’t be a surprise to learn, if you didn’t already know, that his parents were artists who encouraged him to make things, that he had a strong sense of play, that he never stopped learning, never stopped creating.

Add in his competencies—a degree in mechanical engineering from Stevens Institute of Technology, then studies at New York’s Art Students League and art school in Paris—and his 50 years of success (toys, oil portraiture, abstract paintings, wire sculpture, which he basically invented, even jewelry) would seem foreordained.

The Calder Foundation, based in New York and founded by his grandson Alexander S.C. Rower and the Calder family in 1987, is now allowing us to see even more. They have spent their first decades assembling and preserving more than 22,000 documents and artworks; now they have opened some of their treasure in an online research archive (the archive itself is not open to the public).

The online presence is deep. Family pictures, even pictures of early projects, go way, way back—and then way, way forward, not stopped even by Calder’s sudden death from a heart attack at age 78 in 1976.

These photos (and information) culled from the foundation website give an idea of the richness of the artist’s life and work—way, way beyond the artist we think we know.

Promise of things to come: In 1909, at age 11, Calder presented his parents with Christmas presents that included a 4½-inch dog made of bent sheet metal. / © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Calder’s other 1909 holiday gift to his parents was this 4½-inch duck, which rocks back and forth when tapped. / © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

That same winter, Calder created this Animal Zoo Puzzle for his father’s birthday. The challenge was to move the animals from their pens without having two in one pen at the same time. The game, one of many Calder would create during his lifetime, measures 4 by 6 inches and is in the collection of the UC Berkeley Art Museum. / © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

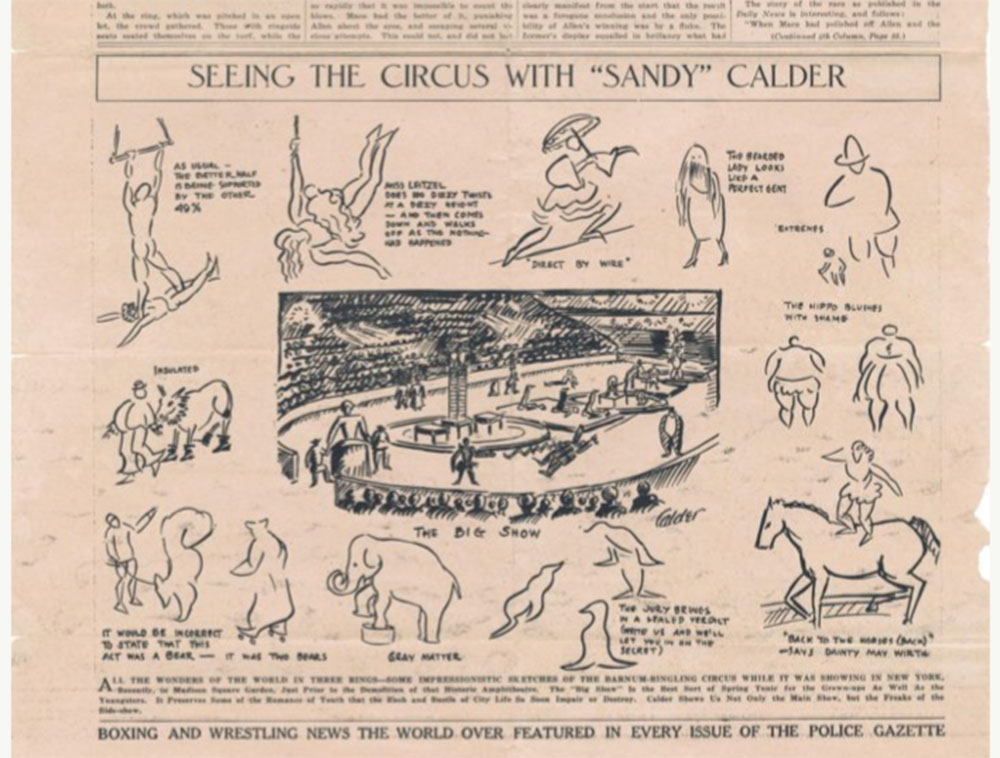

While still attending the Art Students League, Calder was an illustrator for the National Police Gazette in 1925. The paper, based in NYC, sent him to the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus—for two weeks(!) to “cover” the happenings there. This seems to have ignited his lifelong fascination with the mechanics and thrills of the circus. He even created his own. / © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The whole idea of the circus stayed with Calder, and he created his own “Cirque Calder” in Paris in 1926-31, creating functioning wood and tin and wire figures that, in the end, would fill five suitcases as he traveled around to show it off. A 1927 movie clip shows Calder demonstrating his troupe of kinetic sculptures, a kind of performance art. / © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

No one can say the man didn’t love a project. Anticipating World War II, in 1933 Calder and wife Louisa left Paris and bought this dilapidated 18th-century farmhouse in Roxbury, Connecticut. The icehouse became Calder’s studio. / © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

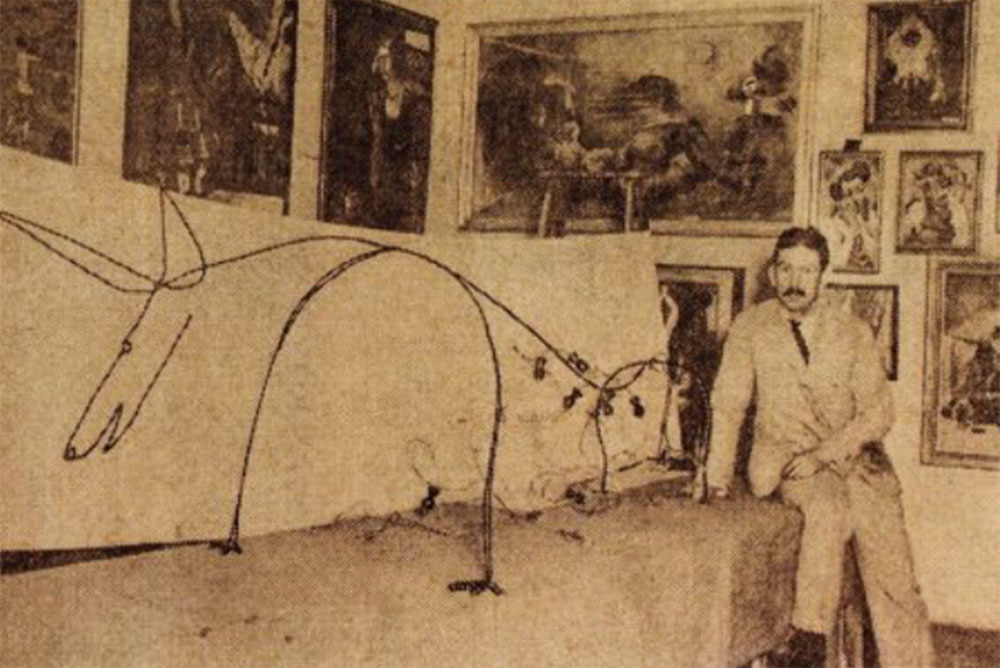

Calder’s “Romulus and Remus” dates from 1928. (The young “Romans” are hard to see in this vintage photo.) The wire-and-wood piece is in the collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in NYC. / © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

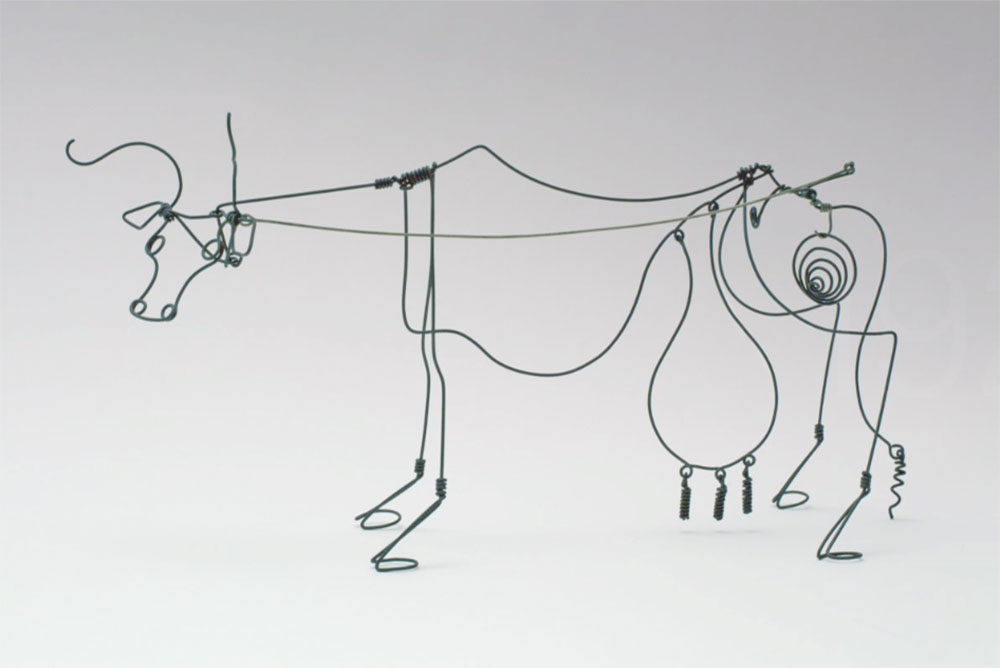

This wire work, “Vache” (Cow), dates from circa 1929 and is owned by the Calder Foundation. After his important and productive stay with Louisa in France, Calder gave all of his works French titles, no matter where he made them. / © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

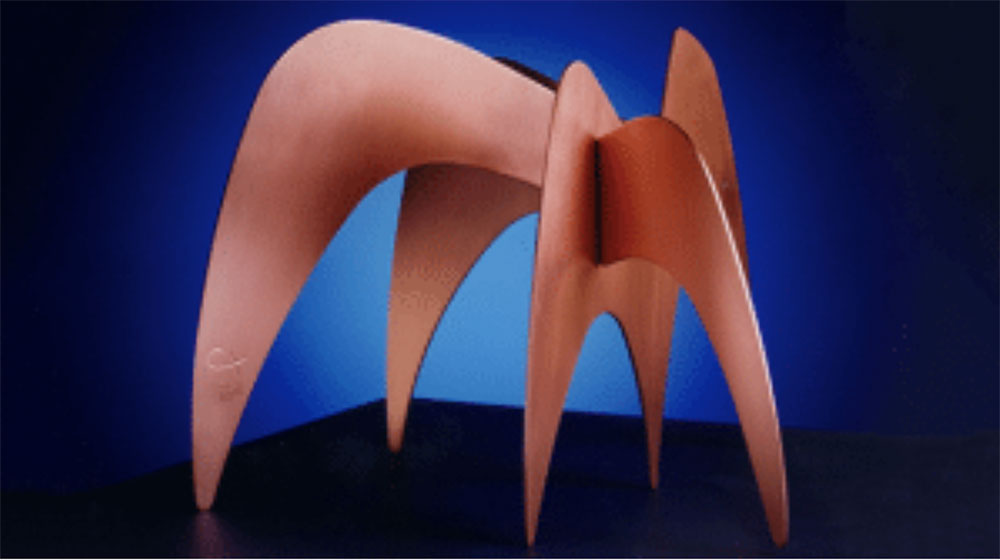

The stabile “Elephant Walking” by Calder is the symbol of The Ellies, the awards for editorial excellence handed out each year by the American Society of Magazine Editors.

Calder reviewing the installation of “.125,” commissioned for Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy International Airport), 1957. / © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“Floating Clouds,” a monumental 1953 work by Calder, was originally conceived as an outdoor art piece for the University of Caracas in Venezuela. But the project was rethought and the laminated-wood panels were installed inside the Aula Magna, the school’s auditorium, to improve the acoustics. Result: The hall, according to Wiki, has some of the best acoustics in the world. “Floating Clouds” (sometimes called “Flying Saucers” by the artist) were mentioned specifically by UNESCO in declaring the campus a World Heritage Site.

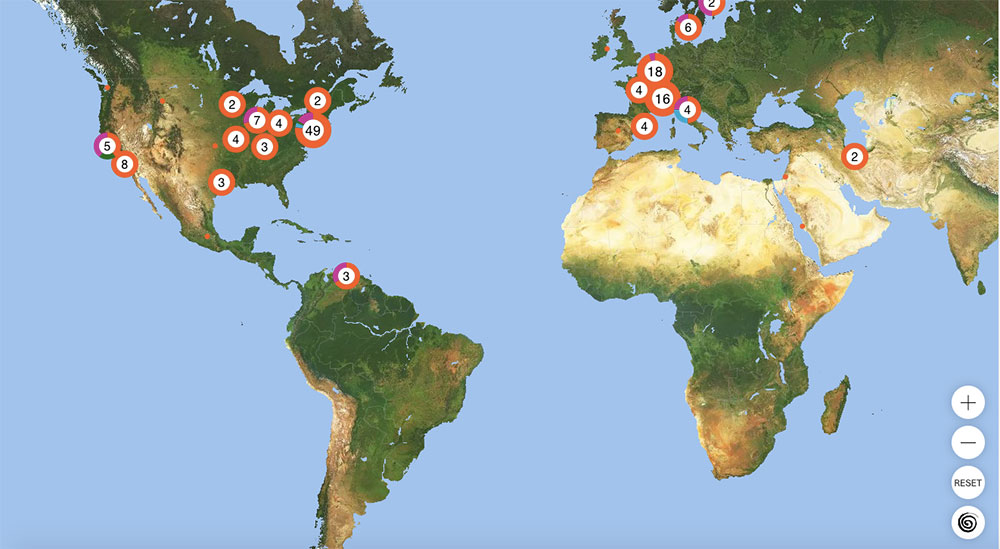

An interactive map on the Calder Foundation site lets visitors locate the artist’s far-flung work. / © Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Delightful! Art that soars, so we do, too.

I had a WONDERFUL time combing through the online stuff. It’s just marvelous!!