“The Miyajima Shrine in Snow” is a 20th-century image by Kawase Hasui. In reviving the landscape tradition, the goal was to capture not only the physical beauty of Japan but also the weather and the mood of the time and place. Woodcut printing by S. Watanabe, in Tokyo. / Photo © Japan House Los Angeles.

By Nancy McKeon

I’VE LONG enjoyed looking at the occasional Japanese woodblock print, but only superficially, not knowing what I was looking at or for. This evening I found my way in.

A wonderful hour spent listening to Meher McArthur, an Asian art scholar, was the key. The occasion: an exhibit she curated at Japan House Los Angeles, Nature/Supernature—Visions of This World and Beyond in Japanese Woodblock Prints. The interactive exhibit is mounted in the gallery but is virtual while the museum is closed.

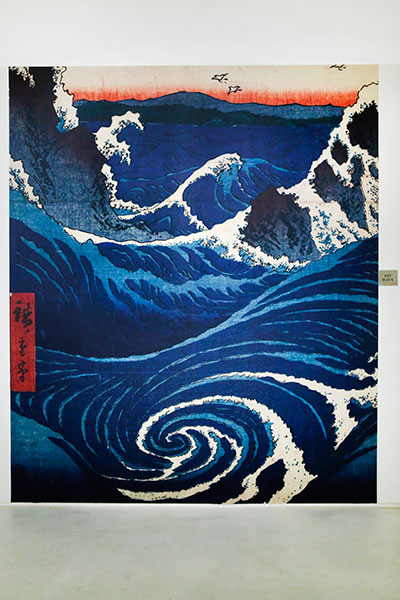

“Whirlpools and Waves at Naruto, Awa Province,” from the series “Views of Famous Places in the Sixty-Odd Provinces,” by Utagawa Hiroshige, circa 1853. / Photo © Japan House Los Angeles.

Woodblock print arrived in Japan from China and Korea in the seventh century along with Buddhism and was a rudimentary vehicle for dispersing Buddhist images and teachings. Only in the mid-17th century did it begin to enjoy secular application, with images controlled not by Buddhist priests but by commercial publishers in Edo, Japan’s political capital and today’s Tokyo. Pulling from the extensive woodblock-print collection at Scripps College in Claremont, California, where McArthur recently taught, Japan House’s show focuses on even more recent times, the century from about 1830 to 1930.

The “Nature” part of the show homes in on the Japanese reverence for their islands’ landscape and their enthusiasm for traveling to experience it. For the privileged, a series by Utagawa Hiroshige, “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō,” could almost be called a travel guide or souvenir for the famous route between the shogun’s capital, Edo, and the imperial capital, Kyoto. For those not able to travel, the prints could serve as armchair travel, collected in albums and shared with friends. The “stars” of the images are the mountains in the background, the lakes, the little bridges; but there is also the human element, small and sometimes humorous: pilgrims getting pummeled by rain, servants rubbing their feet, tired of carrying a rich traveler in his palanquin, etc.

The show’s “Supernature” counterpart is the more fantastical and the one exploring Japanese folklore, with its stories of mischievous beings, such as those inhabiting foxes, who guard the rice crop (catching the rats that would otherwise eat it), and more diabolical ones, such as ghosts seeking revenge on evil humans. Knowing the players and their attributes deepens understanding of the images, just as knowing why, for instance, St. Agatha proffers her severed breasts on a plate; but, similarly, not knowing Christian iconography or Japanese folk stories doesn’t get in the way of immersing yourself in the color and energy of the images.

“Cherry Blossom Viewing at Mount Goten” by Utagawa Hiroshige, c. 1832-1855. Clearly Washington DC is not the only place obsessed with its cherry blossoms, which were, famously, a gift of Japan to the US. / Photo © Japan House Los Angeles.

What struck this “visitor” to the Japan House LA show was the serenity of the landscapes and the traditional images of geishas and other characters from Edo’s worldly entertainment district and the contrast with the animation and sometimes violence of the supernatural images. The Japanese spirit world has spirit in spades!

Humans clearly have to watch out for the Nekomata (monster cat) Bridge over the Nekomata River at Sugamo, shown in this 1864 print by Utagawa Kunisada. Yokai, or supernatural monster animals, and tricksters are some of the elements of Japanese folklore. This yokai can quite obviously cause fires, as seen from the red tongues of flame emanating from that frightening mouth. / Photo © Japan House Los Angeles.

“Famous Sights of Nikko Hannya and Hōtō Waterfalls” by Yōshu Chikanobu, 1891, depicts Japanese as appreciative tourists in their own country. But in this print the glorious detail of the fabrics in the foreground compete fiercely for attention with the landscape at hand (and could be said to have won the day). / Photo © Japan House Los Angeles.

There’s ample time and space given to individual images in the show, but do take the time to set the table for yourself by watching McArthur’s video explanation of what you’re going to see. Perhaps it will open the door to this fascinating, and gorgeous, art form for you too.

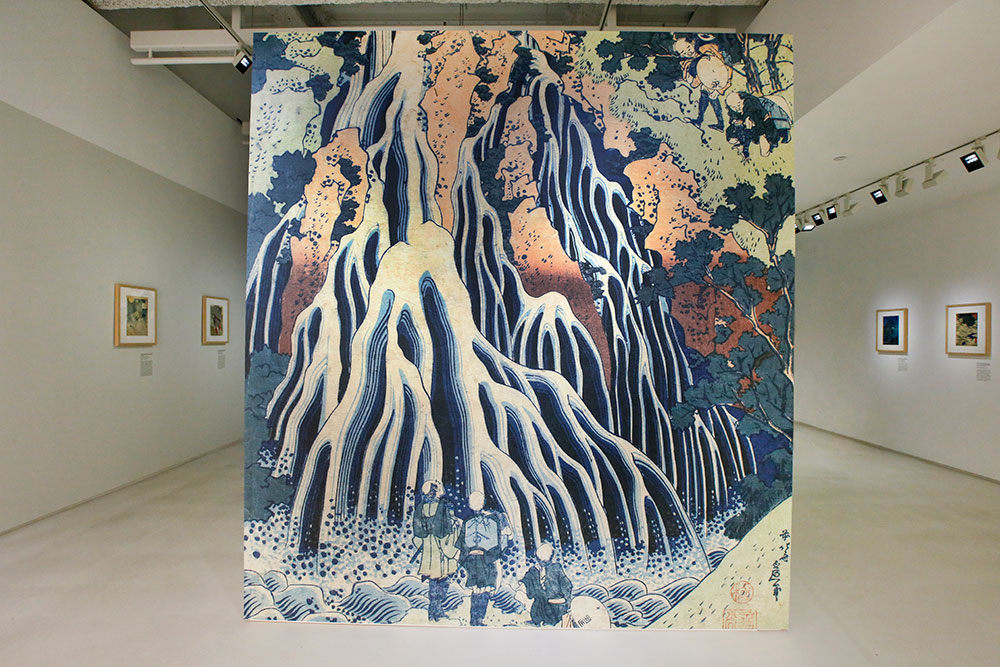

Highly stylized, and therefore arguably unnatural, this image of famous waterfalls in the Nikko region of Japan manages to look like the roots of a tree or even blood vessels. It was created by the famed Hokusai (he of the “Great Wave of Kanagawa”) around 1830 and served as a vehicle for showcasing a wonderful new synthetic color, Prussian Blue, brought in from Europe. Another thing the image reflects is the passion of privileged Japanese for travel, as depicted by the tiny travelers at the very base of the waterfall, dwarfed and awed by its size and splendor. / Photo © Japan House Los Angeles.