I WAS WRITING a story for The Washington Post on Fall Fashion Week in New York. The year was 2012. I was standing on the sidewalk outside what I will always remember as O’Neal’s Baloon* (although the bar-restaurant hasn’t been called that for years). I had paid particular attention to my outfit that day, wearing a burgundy cocoon vintage coat by Kenzo, a multi-stripe Epice scarf and Dries van Noten olive boots. Because you never know, Bill Cunningham might photograph me. To my complete amazement, I saw the legendary NY Times lensman snap my picture. No matter that it didn’t appear in his column that weekend, I won’t forget the thrill of that moment.

— Janet Kelly

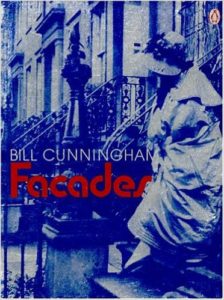

Bill Cunningham’s 1978 book, “Facades,” which blended New York architecture and historical fashions. His model was fellow photographer Editta Sherman. COVER PHOTO: Poster from the 2010 Richard Press documentary “Bill Cunningham New York.” / First Thought Films, Zeitgeist Films via The Dapifer.com.

IT WAS DECEMBER 1984 and New York Magazine editor Ed Kosner wanted us to produce an end-of-year issue dedicated to The Ultimate Style of New York. It was to celebrate the real characters and champions of the city, not just those who clamored for attention (although it did include an essay explaining why Paul Castellano was the “Best of Bosses,” as in mob bosses).

My assignment was to interview Bill Cunningham, who was already a legend for recording street fashion uptown and down, most recently for the New York Times. After a satisfying chat I was to get Cunningham to agree to be photographed for our issue.

Simple, right? Wrong. I vaguely knew how shy and publicity-averse Cunningham was; I didn’t know how wily. He ended my phone approaches with the polite but firm tone I generally use for phone salesmen (yes, they’re still out there). So then I stalked him, which consisted of waiting behind a potted plant outside Le Cirque, the high-profile restaurant that catered to the Ladies Who Lunch (really; the doorman required an explanation) just so I could watch him operate. After Nancy Kissinger emerged and shook his hand, and Pat Buckley flung her arms around him, he backed off and they “allowed” him to photograph them. That may have been a little ego-stroking on the part of Cunningham, but it also allowed him access to high-style private parties thrown by these women, meaning more opportunities for more fashion photos.

More interesting were the anonymous women and men he shot, mostly crisscrossing the corner of Fifth Avenue and 57th Street. He claimed it was the line of the garment, the swagger of the outfit, that caught his attention, not the famous face attached to either. But he managed to capture Vogue editor Anna Wintour one day as she crossed paths with a woman who was wearing the very same Chanel suit from the couture collection. Okay, maybe he noted the twin outfits before he noted the face, but Wintour has since been quoted as acknowledging that “we all get dressed for Bill.”

I finally got crafty enough to capture Cunningham’s attention for a few precious minutes on the phone by launching into a question about someone else. He was happy to talk about her, but when I tiptoed into personal territory he bolted. Politely but firmly.

Getting his picture taken? It was looking like a lost cause until New York’s fashion editor, Wendy Goodman, suddenly realized she had one sitting on her desk: She had taken a Polaroid of a dress in a showroom fashion show weeks earlier and happened to catch Cunningham doing the same.

In the photo Cunningham is looking down at the hem of the dress, serious, paying attention to color and line, and never noticing that he had inadvertently been caught doing a job he continued to do superbly for the next three decades.

—Nancy McKeon

- The “balloon” in the restaurant’s name is spelled wrong because the O’Neal brothers had a sign made reading “O’Neal’s Saloon” before being informed by the New York State liquor authority that it could not, at the time, license any establishment called a saloon, a throwback to the end of Prohibition. Hence, baloon, less expensive than scrapping the entire sign.

The passing of one of the fashion greats. Figured Janet knew him.

Thanks for the footnote about why it’s O’Neal’s Baloon instead of O’Neal’s Saloon. Never knew that although I certainly was a frequent customer back in the day.