The real 1973 ‘Battle of Versailles’ fashion show did not involve horses or fencing foils, as in this vividly imagined panorama by fashion designer and film director Tom Ford. It did, however, establish American ready-to-wear as a worthy challenger to Paris couture, thrusting fashion into the present with modern music, mostly Black models and an energy that stunned the staid French audience. As Ford put it, the battle was won by sportswear. “The victors? Bill Blass, Stephen Burrows, Halston, Anne Klein, and Oscar de la Renta—surely the greatest underdogs in the history of fashion.” The garments in the exhibit are either the very ones that appeared in Paris or were part of the designers’ collections for that year. / Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By Nancy McKeon

THE THING to know about fashion exhibits at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art is that it’s rarely fashion qua fashion. It’s usually fashion as part of culture, of history, of the Zeitgeist. So, the second part of Costume Institute’s homage to American fashion opened last week with an intellectually ambitious series of displays and vignettes, long on interpretation, sometimes short on nouns. And, yes, there certainly was clothing.

One goal of this second half (the first half opened last fall and is still on view) is to reconsider American fashion’s evolution in the 19th and 20th centuries. In recorded remarks to a preview audience, museum officials seemed to be all but apologizing that the museum’s American Wing period rooms, where the vignettes are staged, were collected in an earlier era, with an emphasis on the nation’s British roots and Eurocentric focus. The rooms, they explained, were now “peopled” by mannequins in era-appropriate garb and in some cases “visited” by specters of the unseen hands behind the garments and even the furniture.

So, the museum layered history and context on top of the garments, and then brought in the cavalry in the form of nine film directors—Martin Scorsese, Sofia Coppola, Chloé Zhao, and Julie Dash, to name a few—to add yet another layer, of drama and even emotion, to the enterprise.

I wouldn’t say that the evolution of American fashion kinda got lost in the process, but let’s just say you’ll have to look for it—and then know what you’re looking at.

Fashion photographer turned film director Autumn de Wilde fills the Met’s Baltimore Dining Room, circa 1810, with the audacious décolletage-baring French Empire muslin gown at left, faced off against the slightly more demure American interpretations of the neoclassical style at right. Given Baltimore’s ascendancy as a prosperous port and commercial center, fashions were routinely imported from France, though, as depicted here, local tastes were not always in tune with the less-Puritanical European ethos. / Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

British taste influenced early wealthy American home styles, as in this 1811 Adamesque parlor in Petersburg, Virginia. In the late 1810s, British style also competed with French taste in clothing. Lines were more demure, more staid. The color of the center gown in the Benkard Room, another vignette by Autumn de Wilde, is thought to reflect the vogue for “Clarence blue,” favored by Britain’s Duchess of Clarence. De Wilde wanted to show period rooms and period people in action, being human, not museum pieces. Here a quiet evening of cards has suddenly become very lively indeed. Unseen in this view is the rat that has run up the leg of a nearby chair and the traumatized cat that sits atop the fireplace mantel. / Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Director Autumn de Wilde’s fainting female, left, looks garroted, while the playful pup from another de Wilde room is properly costumed. / Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Richmond Room, from Richmond, Virginia, circa 1810, is the setting for director Regina King’s homage to 19th-century seamstresses and designers who worked behind the scenes to create gowns for the wealthy. This vignette features three designs by African American dressmaker Fannie Criss Payne, born in about 1867 to formerly enslaved parents. Creativity in dressmaking was beginning to be noticed, and Payne wrote her name inside garments she created. The day dresses shown here date from 1905 and 1907, but Payne herself, depicted by the mannequin in the center of the room, lived until 1942. / Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, BFA.com/Matteo Prandoni.

The Met’s Shaker Retiring Room found a gifted match in film director Chloé Zhao, who filled the spare room with 1930s-’40s sportswear by midcentury trendsetter Claire McCardell. McCardell’s approach, especially her “Monastic” and “Nada” dresses, meshed with the simplicity of the Shakers and brought the 1800s aesthetic into modern American women’s wardrobes. An original 1870 Shaker ensemble—light brown dress with full gathered skirt and ivory fichu, or small shawl around the shoulders—is elevated over the McCardell outfits (including a simple wedding gown) as if in benediction. / Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This circa-1870 Renaissance Revival Room from Meriden, Connecticut, provides a lush background for the richly ornamented and exquisitely detailed gowns of Ann Lowe, a New York-based African American designer who specialized in debutante and wedding gowns. Lowe designed Jacqueline Bouvier’s gown for her wedding to John F. Kennedy, as well as the gown Olivia de Havilland wore to accept her Oscar in 1947 for “To Each His Own.” The dresses in the vignette date from the early 1940s until 1968. Director Julie Dash, who created the vignette, added mysterious black figures to the scene to stand in for the unheralded and often uncredited Lowe attending to her original designs. Their headpieces are by Stephen Jones. / Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The most modern of the Met rooms in the exhibit is this 1912-’14 living room by Frank Lloyd Wright for the Francis W. Little Prairie Style house in Wayzata, Minnesota. Storied director Martin Scorsese explained he was challenged to mesh the FLW room with the midcentury gowns of Charles James. His inspiration? To stage them as if they were in the 1945 noir-genre psychological thriller of John Stahl’s adaptation of “Leave Her to Heaven.” So, underneath the glamour, mystery and even danger. / Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

LEFT: A wedding dress by Ann Lowe, circa 1941.

RIGHT: Charles James “Butterfly” ballgown, circa 1955. / Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

LEFT: Dress, Stephen Burrows, 1970s.

RIGHT: Dress, Claire McCardell for Townley Frocks, 1949; from the Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Met. / Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

LEFT: Dress, Jessie Franklin Turner, 1942.

RIGHT: Dress, Norman Norell, 1941. / MyLittleBird photos.

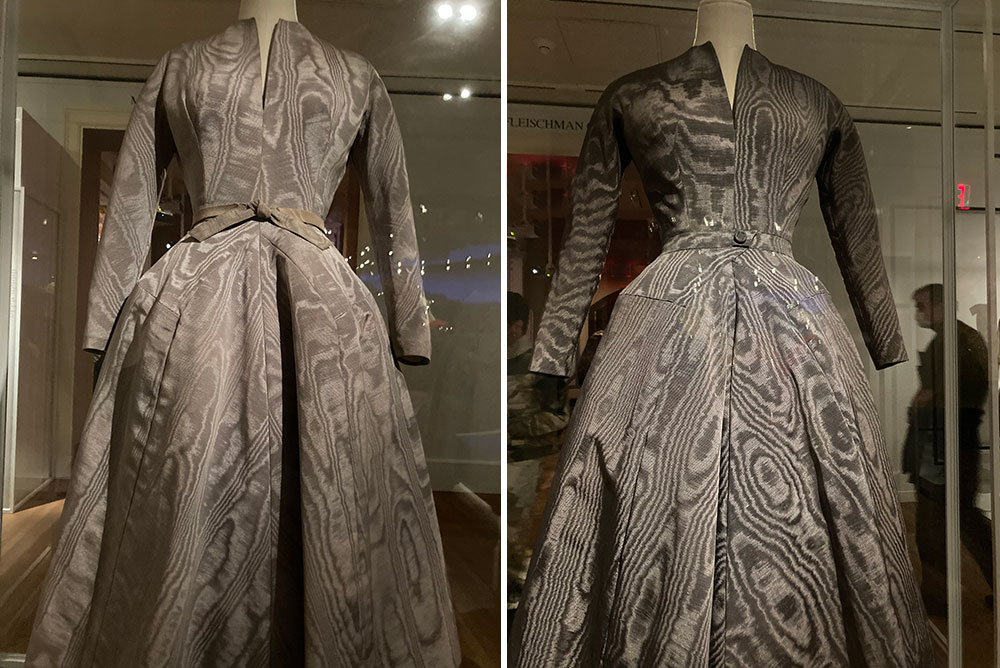

Side by side, these two dresses show that even after breaking free from Paris, American designers would do more than cast an eye toward France. On the left, this “New Look” silhouette dress by Christian Dior meets up, on the right, with an almost line-for-line copy by Hattie Carnegie. Carnegie made some seaming changes and used a button belt, a Dior signature of the time that he did not use with this particular garment (but which Carnegie’s customers may have preferred). / MyLittleBird photos.

In America: An Anthology of Fashion, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue (81st Street), New York, NY 10028; phone 212-535-771; metmuseum.org.

Through September 5, 2022. Free with museum admission.

Thanks for this! Now I don’t feel as if I have completely missed the show.

Great piece Nancy! I used to wander those rooms in high school — they were dark and small, I think, because so few visited them. On weekday afternoons I had them to myself to wander and daydream. Hard to believe now…

so nicely done. looks as though I don’t need to visit in person.

There’s a lot more than I was able to include, so you should definitely visit if you can. That said, the American Wing period rooms, where the little vignettes are staged, are pretty small, and the entrances from which you have to view them (and try to read the captions, in the dark–good luck) are tiny and cramped. I think these pictures are a nice primer and will help when experiencing the show IRL (as the kids say).

Love this.

Me too. This half of the Anthology has more of a through-line than the first half (the “emotional vocabulary” of American fashion–yeah), but the first half is still on view as well. Both exhibits are on through September 5, 2022.