Last fall, the Museum of Chinese in America, which remains Covid-closed, turned some of its sidewalk display windows into exhibits. “Windows for Chinatown” explores the history of Chinatown and anti-Asian racism. This 2020 cartoon by Vera Chow shows earnest immigrants, mostly of color, doing all the crucial Covid work while a white-bread American cheers on TV coverage calling for an end to immigration. The windows will remain in place through March 21, 2021. / From the Museum of Chinese in America.

MANY MUSEUMS, especially art museums, have a radiant quality, ablaze with their riches. They grant us visits with their collections, even suggesting that those of us who visit are the worthier for having passed through their portals. The Met, the Louvre, the Rijksmuseum, the National Gallery—these are the names that immediately come to my mind.

Museums of history have a different mission: Don’t forget what happened, they seem to command. It’s not a scold, exactly, but I always have the feeling that there will be a quiz at the exit and that I will be too dazed to pass. I’m thinking of the House of Terror in Budapest, Schindler’s Factory Museum in Krakow, the Ukrainian National Chernobyl Museum in Kiev, even the National Museum of African American History and Culture in DC. Pay attention!

The Museum of Chinese in America, located in New York City’s Chinatown, seems a bit different, its goals more specific. To start with, it seems to be speaking, with some urgency, to its own community, or rather to Chinese Americans spread across the US, whether in Chinatowns or deeply embedded in the American mainstream. Those are the people being urged not to forget.

To me it presents itself as more a family scrapbook than a curated collection set out with a greater public in mind. And therein lies its charm. Imagine that your great-grandmother left a trunk of ephemera—family pictures, flyers from the summer carnival, a Sears catalogue marked up with her fantasy purchases (remember it was called the Wish Book for a reason). You’ve discovered the trunk and now get to sift dreamily through the finds. Heaven, right?

You may not be Chinese or Chinese American, but you can share in the charm of a few pages dedicated to the Eight-Pound Livelihood. It’s pictures from the turn of the last century of Chinese workers in hand laundries, the classic Chinese American business since the 1850s.

And the term “Eight-Pound Livelihood”? I thought perhaps it referred to the weight of a load of laundry. Wrong. That was the weight of those heavy flat irons used to press out the wrinkles in the clothing of California families and rough-edged railway workers and hardscrabble gold miners.

While the museum’s website doesn’t offer any slick interactive exhibits, it does lay out images from its exhibits over the 40 years since its founding. As the Museum itself says, it is redefining the American narrative one story at a time.

—Nancy McKeon

Not something most of us think about every day: How do you devise a typewriter or a computer keyboard for a language made up of thousands of characters? Two inventors at the beginning of the 20th century took on the challenge and came up with a machine that looks more like a Linotype machine than a standard typewriter. Today, Chinese computing is based on a 1947 experimental typewriter with incredible workarounds. The typewriter above was featured in MOCA’s 2019 exhibition on the development of the Chinese typewriter, “Radical Machines: Chinese in the Information Age.” / From the Museum of Chinese in America.

“Eight Pound Livelihood: Chinese Laundry Workers in the United States” was the Museum’s first exhibit. Through photos and first-hand stories, it explored how Chinese in California entered into the occupation and moved eastward, establishing laundries in cities and towns where they settled. / From Museum of Chinese in Ameirca.

In 2016, the Museum of Chinese in America mounted a retrospective of Ming Cho Lee, one of the most influential set designers of the 20th century, perhaps best known for his groundbreaking abstract sets in the 1960s and ’70s. The image above is from a 1964 Public Theater (NYC) production of “Electra,” which Mr. Lee described as his first “completely nonliteral abstract design.” Below is his set for a 1979 production of Molière’s “Don Juan” at Arena Stage (DC). Mr. Lee died in October 2020 at age 90. / Courtesy of Ming Cho Lee to the New York Times.

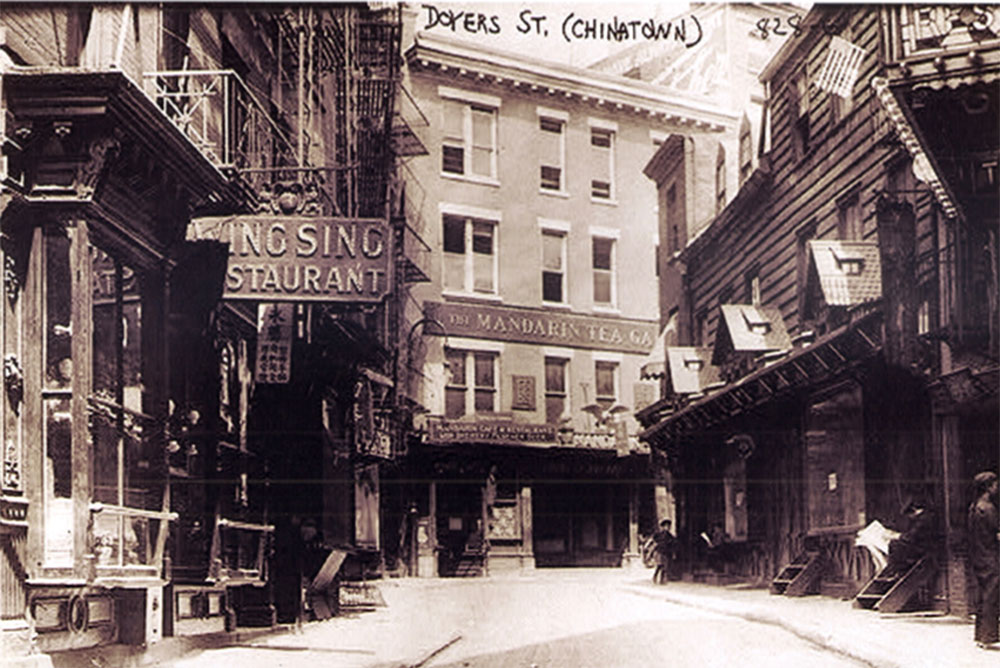

Doyers Street, a crooked little commercial street, is still the heart of New York’s Chinatown. The street signage is gaudier and more colorful today, but lift your eyes and you’ll see a bit of the past. / From the Museum of Chinese in America. Courtesy of Ernest Y. Ng.

Just mention Chinese Laundry and my head fills with the scent. What was it?

I don’t know, but I suspect it had something to do with the hot irons hitting the cold starch in the men’s dress shirts. My father’s dress shirts were what we used hand laundries for when I was growing up. I later used my neighborhood hand laundry (long gone) for my bedsheets (mmmmm!), which gave me the faintest echo of that scent. These days I use I Hate Ironing, an outfit out of London, of all places, and operating in NYC–though come to think of it, the delivery guy I met once was Asian, though I wouldn’t say Chinese American necessarily.