A Different Tree of Life

THE RESIN drips slowly down to the ground, oozing out of precision cuts made in the bark and branches of the mastic tree—a sight locals call “the tears of Chios.” You can think of the process as being just like tapping maple trees for maple syrup, but with nicer weather. Carefully tended fields on the Greek island of Chios are full of these trees. They are a precious commodity going back hundreds, possibly thousands, of years. Dried and sorted, the translucent droplets resemble tiny pearls, their value enhanced by the fact they are found nowhere else in the world.

Many merchants on the island have grown rich on them, so difficult the harvest and so great the demand as an export needed in the manufacture of such items as chewing gum, varnish, adhesives and flavoring.

Except when nature doesn’t cooperate and adverse weather—such as too much or too little rain at the wrong time—interferes. Cultivation is done by hand in early stages, a process greatly determined by tradition. When the crop fails, locals have been known to look elsewhere for blame. “One time during the 1970s,” a friend reports, “it rained during harvest season and the mastic congealed. The locals blamed it on men landing on the moon.”

In good times, apparently, there is more than enough product to go around. Enough, at least, to market the plant’s versatility in a different form, as a personal health and beauty aid. Today, a complete line of these goods is available locally and online: soap, shampoo, creams, oils, facials, etc.—whatever is needed to look better and feel healthier.

Mastic (or its preferred name mastiha, pronounced mas-TEE-hah) long had found use as a sweetly resinated liqueur, sold lately under the luxury brand of Kleos, “glory” in Greek. Mastiha’s medicinal properties, directed at oral and digestive disorders, build on a reputation that promoters say goes back to Hippocrates in the 4th century BC. Shoppers and lovers of botanicals can find a range of products at www.mastic.gr/en-us.

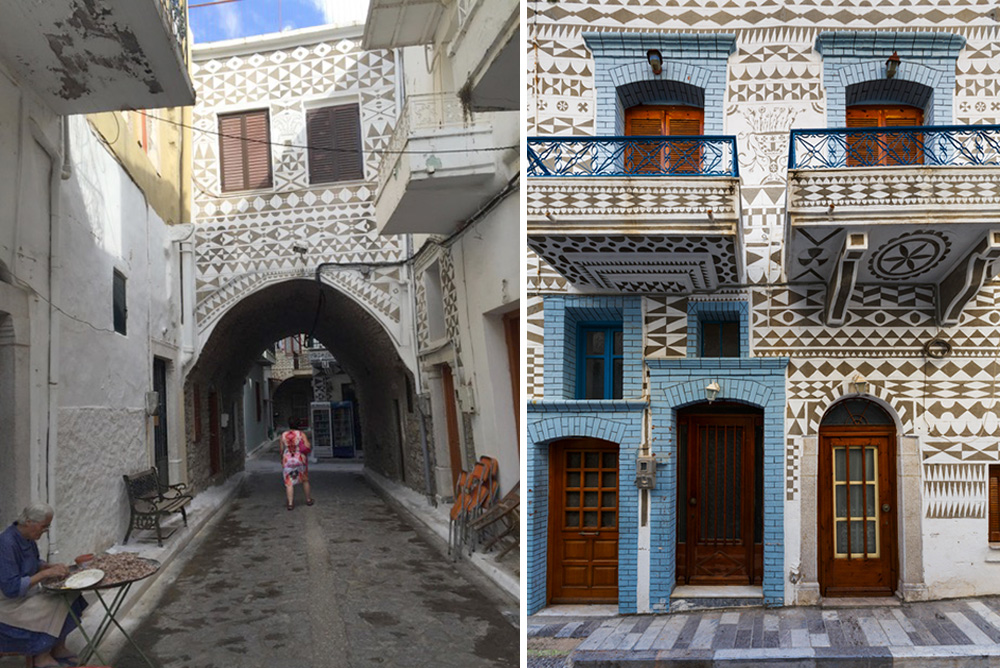

What’s not to love about this northeastern Aegean island, Greece’s fifth largest? The mastikachori for one thing—some two dozen fortified mediaeval villages in the south that have been integral to the plant’s cultivation since the 14th century. Among them is Pyrgi, an eye-opener for visitors who have seen their fill of European walled cities. The town’s unique feature is the startling presence of decorative dark gray and white geometric designs covering the façades of nearly all the buildings inside the city walls. Strings of red tomatoes drying in the sun hang off upper balconies lining the narrow stone streets. During the mastiha harvest season, it’s common to see women villagers bending over wooden trays to sort the precious tears with experienced hands.

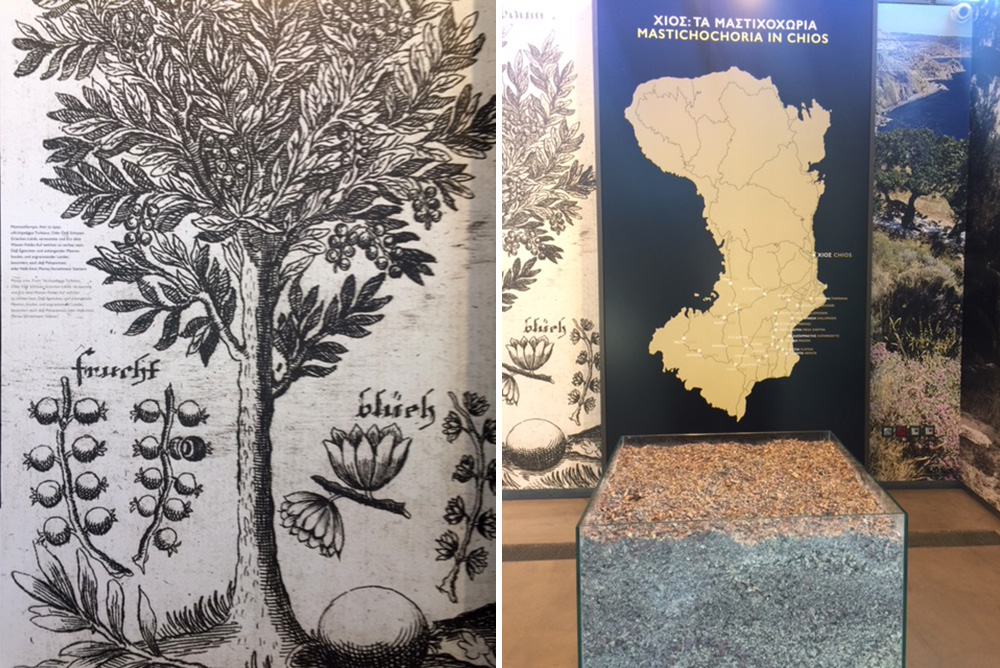

Worth the trip, too, by bus or car, is the handsome new Mastic Museum, not far away. This sprawling glass-walled structure is dedicated to everything you need to know about the island’s most famous product—what UNESCO terms an Intangible Cultural Heritage. The building is splendidly placed atop rolling hills with a commanding view of green mastic trees growing in terraced formation in every direction. Visitors can tour the extensive indoor exhibits and walk freely around outside. There is a cafe and shop, full, as might be expected, of everything mastic, including some superior original jewelry designs. (This visitor couldn’t resist a fabric necklace piece made to resemble the leaves of a mastic, or maybe olive, tree.)

An island famous as home to some of the Greece’s most prosperous shipping families— think Chandris and Livanos—never has needed either mastic or tourism to survive, making it that much more desirable. Accessible by plane and ferry, it sits less than three miles from Turkey, below Lesbos to the north. It’s possible to take day trips to either place from bustling Chios town on the east coast. Not far away, too, is a renowned religious center, the 11th-century Byzantine monastery of New Moni, another UNESCO World Heritage site, containing outstanding mosaics and relics.

Which makes the place especially alluring during spring and summer, and well into fall, when the buoyant seas are warmer. Keep in mind, too, less blissful memories of some of the beaches that saw the arrival, especially a few years ago, of flotillas of refugees in black rubber dinghies coming ashore at all hours, wet and bewildered.

I recall only too well the time I was out swimming in a bikini and saw those rubber rafts full of desperate migrants pull up to the beach, escaping from Iraq and Afghanistan through Turkey, which is visible a few miles away. I quickly scurried back to my room to change into more modest cover, then ran to take the bag of shoes and boots I had carried with me from home, a donation from a DC neighbor.

A really sorry sight, but at least the day was sunny, no lives were lost, and there were public showers for the men (women didn’t venture to do it) and buses to take them into town. Just one step more on their long journey to a hoped-for new life.

Many refugees remain cloistered out of sight in crowded conditions elsewhere on Chios—many thousands more on Lesbos—awaiting a transfer to the mainland that may never come.

But the seas, the trees of Chios, the mastic, will—nature’s moods allowing—be there as always.

—Ann Geracimos

Ann Geracimos contributes periodically to MyLittleBird and for her own blog, www.urbanities.us, where she writes about city living—in cities and places that feel like cities.

Interesting post. And beautiful pictures.