Artist Frank O. Salisbury painted this portrait of Marjorie Merriweather Post Hutton in 1934. For the portrait she wore a silk satin ivory dress with a red silk velvet drape trimmed in white fox. / Courtesy Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens.

Among the dresses displayed throughout the mansion is this afternoon dress of organza and lace created around 1903 by a French designer. Visitors will find it in the French Drawing Room which, on the day of our visit, was in a slight state of disarray while crews readied the new exhibit. / MyLittleBird photo.

Definitely not from the Eileen Fisher school of design, Post’s dresses often were lush, complicated, heavily ornamented concoctions. The studded metal beading on the gown above is a perfect example. / MyLittleBird photo.

An evening at home meant retiring to the library wearing a lounging gown of beaded blue velvet. The deft, and very clean, hands of Howard Vincent Kurtz, Hillwood’s associate curator of textiles and curator of the exhibition, and docent and collections volunteer Celia Steingold adjust the gown so it hangs perfectly on its mannequin. / Left, MyLittleBird photo, right photo courtesy Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens

Post wore this afternoon dress of taffeta, organza, lace and chiffon the night she became engaged to Edward Bennett Close. / MyLittleBird photo.

A custom traveling dress by designer Ellen Widoff of New York from around 1910 made of purple linen-backed velvet also features ivory lace, jet beading, boning and bright pink silk satin. / Courtesy Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens.

Post , a fervent advocate for the women’s vote, wore this Suffragette suit as a member of the New York State Woman Suffrage Party during a visit with President Woodrow Wilson in 1917. / Courtesy Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens.

For this 1921 portrait Post wore a gown similar to the evening dress at left. She often ordered multiple sets of the same style. This evening dress features a divided skirt inspired by harem pants. The most visible difference between these two dresses is the color of the netting at the sleeves and waist. / Courtesy Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens.

This tubular, waistless dress typifies many of the radical changes in women’s fashions of the 1920s. The dress is slightly flared at the bottom, a feature that made it particularly well-suited to dancing. Its accessories include a matching slip, cape, purse and fan in the same striking combination of cream and cobalt blue silk velvet, embroidered with rhinestones. / Courtesy Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens.

These twin evening gowns represent one of Post’s favorite styles. She had the gowns, made of satin, tulle and silk crepe, in both copper and ivory. The gowns were basically the same but featured slight differences. / MyLittleBird photo.

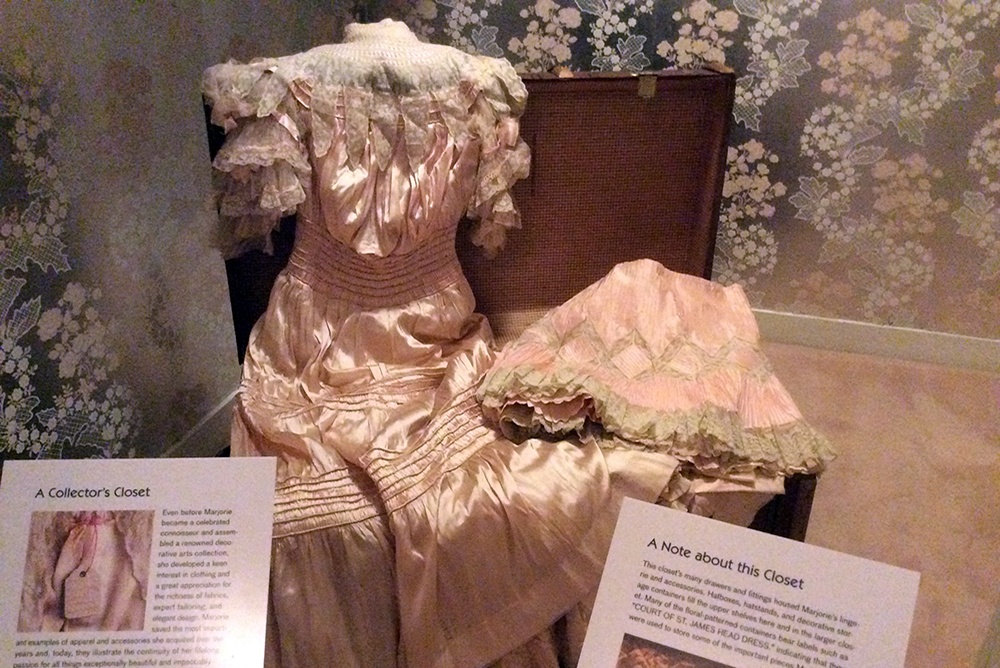

A gray dinner dress by Christian Dior is made of silk taffeta and decorated with cut steel and glass beads. The dress is worn with a petticoat, but not the original one. To save wear and tear on the delicate originals, Kurtz buys new petticoats and hems them to the proper length when dresses go on display. / Left photo courtesy Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens, right photo MyLittleBird.

On display in Post’s closet is this black silk taffeta evening dress. The rounded shoulders and V-neckline illustrate the change to a fuller silhouette that took place at the end of the 1940s. / MyLittleBird photo.

Oldric Royce was one of Post’s favorite designers from the late 1940s through the 1960s. Intricate smocking and clear rhinestones set off this Royce evening dress from 1955. The dress was made of green silk organza and is on display in the dining room. Post also commissioned the same dress in gray. / MyLittleBird photo.

In 1968 Designer Oldric Royce created this gown of raw silk, cotton lace and beading, which Post wore to the American Red Cross Ball in Palm Beach that year. / Courtesy Hillwood Estate, Museum and Gardens.

Michele Hopkins, a curatorial intern with the Smithsonian’s decorative arts program, and Elizabeth Lay, a curator with the Montgomery County Historical Society, have been tasked with readying the dresses to be displayed in the Adirondack building. Here, a dress that has been on display throughout the summer is returned to its “coffin” for storage. The delicate clothing is handled with extreme care. / MyLittleBird photo.

Mannequins in the Adirondack building wait to be dressed in the clothing chosen for colder months that make up the second part of “Ingenue to Icon.” / MyLittleBird photo.